茶 FIRST IMPRESSIONS

茶 REVIEW OF BOOKS & FILMS

[ESSAY] “From Star to Performer-Worker: Rethinking Anna May Wong Through Labour” by Anna Nguyen

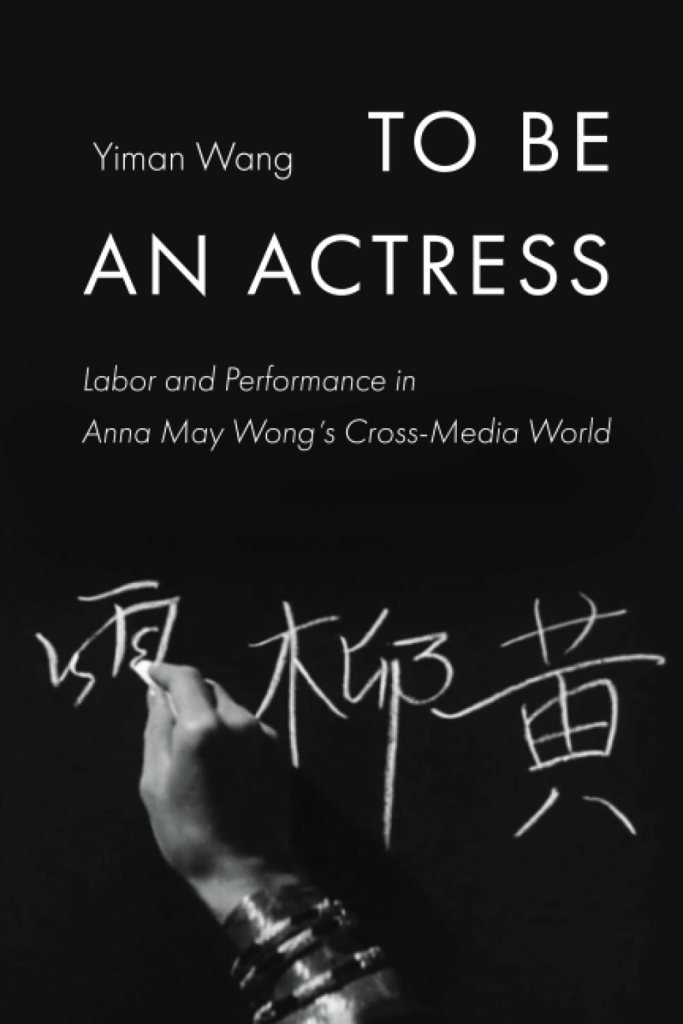

Yiman Wang, To Be An Actress: Labor and Performance in Anna May Wong’s Cross-Media World, University of California Press, 2024. 265 pgs.

After reading Yiman Wang’s expansive analysis of Anna May Wong’s filmography, I found myself reflecting on my own participation in media criticism. In a different lifetime, when I was a Ph.D. student in a communications department in Canada, I served as a teaching assistant for a media-criticism course. A student came to my office hours to discuss the required short critical piece they had to write. They wanted to examine the role of Long Duk Dong in Sixteen Candles (1984).

“Yes, okay, what about the character?” I asked the student.

“I want to talk about representation.”

“Okay. Representation in the West? Why are we only ever worried about the West?” The final question was primarily directed at myself.

“Because we’re in the West,” the student responded, though it certainly sounded more like a question.

We, both in academia and beyond it, have never been able to avoid the pitfalls of representation as a necessary mode of critique. Yet representation, I find, can be informed by the logic of eugenics, wherein only a person’s appearance and skin colour are prioritised at the expense of other political categories. As an instructor, I can only pontificate through learned conceptual theories; as a crude analyst, I dismiss the ease with which we consume media in order to catalogue its positives and negatives. I am more concerned with who is telling the story, and in what ways. I am less interested in narratives that reify capitalism and colonialism.

As a result, I often find myself looking beyond Western borders. At the same time, I question what cinematic borders actually mean while reading about Wong, an American-born actress about whom I previously knew very little. Wang’s To Be An Actress examines Wong’s filmography with complexity by shifting our conventional understanding of star studies towards performer-worker studies, in order to “amplify marginalized voices, so as to reinsert nonwhite and gendered labor as the very foundation for star glamour” (p. 5). Wang refuses to produce a sweeping biographical account that canonises Wong’s life and instead anchors artefacts from the actress’s four-decade-long career to “foreground a consistent pattern in Wong’s life-career: the ongoing negotiation, contention, and co-constitution between her self-narrativization and journalistic (mis)representation” (p. 3).

This rigorous examination of Wong’s labour is notable insofar as it proposes an alternative framework to the more familiar lenses of cosmopolitanism, fashion, racialisation, and European reception (p. 3), often articulated through “yellow objecthood” (p. 11). Wang connects Wong’s labour and agency in order to reject facile binaries of victimology and triumphalism, noting that both “share the neoliberal presumptions of individualist agency, unilineal teleology, and presentism” (p. 4). Wong’s individual merits are frequently “credited for elevating her to a model minority par excellence who finally wins the battle, in our enlightened historical hindsight” (p. 4).

This is not the story Wang seeks to renarrativise, a point the author makes clear in the prelude by observing how historical legacies are so often enmeshed in capitalist reductions. In 2022, Wong’s face was memorialised on a quarter. The following year, her image was reproduced as a red dragon-gowned Barbie doll in Mattel’s Barbie Inspiring Women series, released to coincide with Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month. Both commemorations appeared, perhaps strategically, years after the COVID-19 pandemic and the surge in anti-Asian sentiment that accompanied it.

Although Wang contextualises Wong’s work in the present moment, her method relies on speculative historiography, which allows the scholar to “reanimate what dominant archives have failed to recognise, but also have failed to completely eradicate” (p. 7). This approach also complements an alternative spatiotemporal ordering, which she defines as the “anachronotope,” a portmanteau of anachronism and chronotope, used to reveal non-hierarchical time-spaces. This intervention is significant, as archival work often becomes mired in materiality and linearity. Instead, Wang draws on archival research related to Wong and observes that much of the documented commentary during Wong’s career and lifetime came either from white reviewers who fetishised Orientalism or from Chinese reviewers who evaluated her work in relation to a Chinese ethno-patriarchal nationalism (p. 7).

Each chapter examines and reinterprets Wong’s work and legacy by strongly suggesting that the performer herself was aware of her own performance, or what Wang terms a self-citational authorship. In the first chapter, “Putting on a Show,” Wang argues that Wong was highly conscientious in deploying irony through self-Orientalisation in her Hollywood roles during the silent-film era of the interwar and wartime periods. This choice to self-fetishise visually parallels José Esteban Muñoz’s concept of disidentification, defined as a means of managing and negotiating historical trauma and systemic violence (p. 30). Such a deployment of disidentification “locates agency in the amphibious position between the center and the periphery” (p. 30) by producing a spatial negotiation.

In the following chapter, “Putting on Another Show,” Wang shifts her focus from film to Wong’s theatrical work in Europe, America, and Australia. Drawing on Wong’s own writings, interviews, and photographs, Wang documents the actress’s multi-sited stages, which “challenge race-gender hierarchies in the settler-colonial entertainment industries in the US and Australia” (p. 64). This transition from the visual to the linguistic is significant, as performers who had gained prominence in silent films were increasingly marginalised. For Wong in particular, the stage offered an opportunity to “produce a multilingual ethno-cosmopolitanism, which troubled the ocular-centric Orientalist imaginary” through her mannered use of English, French, and German (p. 65). Wong introduced this speaking method following her theatrical debut in The Circle of Chalk in London in March 1929 (p. 65). She was not the only Chinese-heritage actress in the production. Both Wong and Rose Quong were sexually and racially objectified in a play that relied on stereotypical costuming, set design, and music. Wang also includes excerpts from theatre criticism that lamented Wong’s vocal performance, with one review notably referring to her “ineffective elocution, and her American accent” (p. 67).

The third chapter, “Shifting the Show: Labor in the Margins,” returns to Wang’s central interrogation of Wong’s continual negotiation of her career through nuanced performance. Here, Wang focuses on Wong’s minor roles in order “to scrutinize the margins and the background” (p. 97), drawing on Black film studies and feminist studies. Marginalised space, Wang argues, can both “constitute and problematize the center all at once” (p. 99). She engages with archival lacunae and supplements the analysis with QR codes placed alongside scene stills, enabling readers to experience Wong’s performances directly. Video 3.2 features a visibly emotional Wong playing a maid named Loo Song in the 1927 film Mr. Wu. Wong’s role is minimal in a film in which white actors portray Chinese characters. Loo Song listens as a British grandmother dreamily describes her future grandson’s Aryan features, while remaining aware that he is having an affair with a Chinese woman. Wang interprets Loo Song as the “recipient of unbridled racism” (p. 106).

Shifting away from roles defined by overt racial suffering, the fourth chapter centres on the deeply institutionalised racist casting practices of the 1937 film The Good Earth. Wong auditioned multiple times for the lead role of O-Lan, which was ultimately awarded to a white German actress. She declined the minor role of Lotus, characterised as a stereotypical Chinese concubine. This experience inaugurates “The Show Must Go On,” as Wang moves beyond a narrative of failure and juxtaposes it with Wong’s subsequent trip to China. Threads from earlier chapters resurface, particularly the extent to which Wong’s othering had become the burden of her performances. During her theatrical work, Wang notes that the actress’s “racialized identity came under intense and bizarre scrutiny in both American and Chinese press” (p. 78). In 1936, Wong travelled to China, where she filmed a travelogue, an episode for a television programme, and a short film for MGM. Wang analyses these works to consider how Wong “resisted normative identity politics” (p. 136). Although Wong’s ancestral dialect was Taishanese, spoken primarily among diasporic Chinese communities, she nevertheless required an interpreter during her travels (p. 144).

The final chapter, “Encore the Performer-Worker,” returns to digital technology and speculative narration. Wang extends her analysis to contemporary media, including a documentary, a short film, and an art installation, in order to further reflect critically on Wong’s work. The chapter opens with an epigraph in French from Derrida, whose words Wang engages with seriously. As Wang explains, Derrida questions “a text’s or a love letter’s sure arrival at a destination, an assumption predicated on the singularity of the sender, the receiver, and the message” (p. 166). He proposes “destinerrance” as a temporal rather than static concept, a framework Wang employs to analyse how Wong’s work continues to be imagined and reimagined by the public.

As someone who consumes and writes about media, I find myself increasingly fatigued by long think-pieces that essentialise representational regimes, allowing them to function as both the starting and ending points of analysis. For this reason, I greatly value Wang’s book, which foregrounds acting as a vocation, albeit a constrained one, for Anna May Wong, and traces how the actress’s experiences travelled across the globe. It may not surprise readers or film enthusiasts that Wong defied racism in Hollywood, nor should it surprise them that she “questioned the Chinese government’s dismissive rejection of the working-class Chinese diasporic communities from which she came” (p. 136). These multiple contexts of reception are crucial if Wong’s work is not to be simplified into a linear narrative.

Historical considerations are, of course, essential to understanding Wong’s labour choices. Yet history has repeatedly found ways to reward and eulogise overlooked performers through the tokens of capitalism. This is not the form of memorialisation we should seek, and Wang demonstrates that there are more rigorous and ethical ways to renarrate the achievements of figures such as Anna May Wong.

How to cite: Nguyen, Anna. “From Star to Performer-Worker: Rethinking Anna May Wong Through Labour.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 3 Jan. 2026, chajournal.com/2026/01/03/anna-may-wong.

Anna Nguyen left her PhD programme and reworked her dissertation into a work of creative non-fiction while studying for an MFA at Stonecoast, University of Southern Maine. Her work brings together literary analysis, science and technology studies, and social theory to examine institutions, language, expertise, citation practices, and food. She is currently undertaking a second MFA in poetry at New England College, where she also teaches first-year composition. She is the host of the podcast Critical Literary Consumption. [All contributions by Anna Nguyen.]