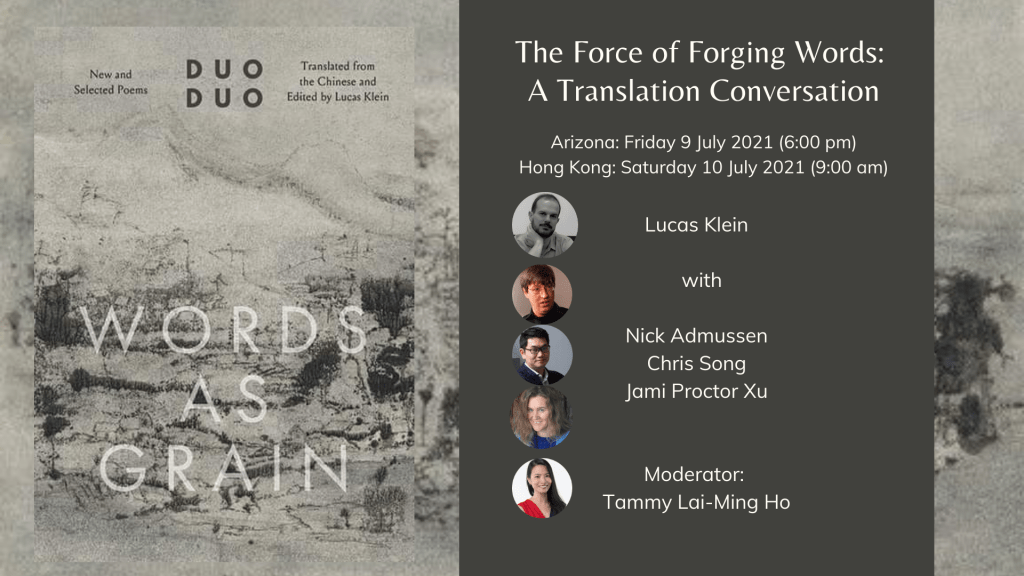

In “The Force of Forging Words”, a poem in Words as Grain: New & Selected Poems by premier Chinese poet Duo Duo 多多 (Yale University Press, The Cecile and Theodore Margellos World Republic of Letters series), translated by Lucas Klein, Duo Duo writes: “outside force, continuing on / from enough, is insufficient hallucination // … // this is rationale’s wasteland / but the ethics of poetry”.

Thanks for inviting me to join “The Force of Forging Words: A Translators’ Conversation”. I received a copy of Words as Grain a couple of days ago, and was extremely happy about it. Lucas Klein and I had a bit of an exchange about Duo Duo’s poetry when he started to translate his poems. He translated all of the poems first and then made the selection from the translations. This is very admirable. I read Lucas’s translation drafts of Duo Duo’s poems. At the time, I found his poems very repetitive, especially those early ones. Lots of abstractions, wild images, unexplained logic behind the poems. It’s very easy to fall prey to such stereotypes reading Duo Duo’s poems. But reading this book, I don’t feel the same kind of repetitions. Perhaps it’s because Lucas’s way of arranging the poems anachronically. I believe Lucas will tell us more about this a little later. Here, I would like to answer some of the questions raised by Tammy Lai-Ming Ho, Cha‘s editor-in-chief and the moderator of the panel.

What are the ethics of poetry?

Before this talk, I had not truly considered the question. As a poet, I write only when life speaks to me—in an instant like lightning. Inspiration arrives in a form akin to alchemy, fusing emotion and idea into a singular image. Around that image, I construct the poem. In this process, I enter what might be called a state of no-self 無我, and the notion of an ethical dimension to poetry rarely asserts itself.

If there is indeed an ethics of poetry, I believe it lies in a kind of honesty—a fidelity to one’s own emotions and ideas during the incubation of the poem. I was reflecting on W. H. Auden’s “September 1, 1939″, which he later described as “the most dishonest poem I have ever written”. He neither felt nor believed what he expressed in it. In that sense, I would argue that the ethics of poetry demand that a poem remain faithful to the writer’s authentic feelings and thoughts.

.Is poetry the wasteland of the rationale, or of the rational?

I can’t say I agree with that. Poetry is as much about the irrational as about the rational. If we believe that poetry is the wasteland of the rational, then we are believing in a certain romantic myth about the birth of poems. As if, a poem would write itself without our least conscious effort. I believe poetry is an art of words as it always has been. It is the work of genius, and it also requires craftsmanship. Even with the most brilliant idea about a poem, we still need to think about its overall structure, its logic, its context, the formal elements that echo the meanings even when they’re unstable. It’s very difficult, if not impossible, to completely let go of the rational when writing a poem. When translating a poem, I become even more conscious about the process of artificially building the poem in a different language which leans even more to the rational than the irrational. I believe poetry has a realm that’s beyond human reasoning, but I don’t believe words are completely autonomous. That’s why I will read “Words” 字 in the reading session later. Not because it speaks to me, but because it doesn’t speak to me.

Is translation a kind of hallucination, and is it sufficient?

As I understand it, hallucination prompts us to question our experience in reading translations. The issue of hallucination is also an issue of authenticity. Is anything in a translation authentic on the part of the original author? Does what we get from a translated poem present the original author’s authentic experience? The obsession with authenticity has plagued translators ever since translation came into being. I do think that it’s healthier for us to just embrace hallucination. Translation is hallucination, but it doesn’t mean that hallucination is a bad thing. What’s authentic to the author of the original poem is not what’s authentic to the reader of its translation. If we accept the original poem and the translation are authentic differently, then hallucination can produce something authentic on the part of the reader. In a sense, the translator is a producer of both hallucination and authenticity.

I think this question as to whether it is sufficient is intriguingly related to another question—do we read a translation as always related to the original or as a poem that stands on its own? I always think a translation should be self-sufficient. Anything that comes from a comparative reading with the original is supplementary or additional.

How to cite: Song, Chris. “Entering a State of No-Self: Some Thoughts on Poetry and Translation.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 11 Jul. 2021, chajournal.blog/2021/07/11/no-self/.

Chris Song is a poet, translator, and editor based in Hong Kong. He has published four collections of poetry and many volumes of poetry in translation. He received an “Extraordinary Mention” at Italy’s UNESCO-recognised Nosside World Poetry Prize 2013 and the Young Artist Award at the 2017 Hong Kong Arts Development Awards. In 2018 he obtained a PhD in Translation Studies from Lingnan University. More recently he won the Haizi Poetry Award in 2019. Chris is now Executive Director of International Poetry Nights in Hong Kong and Editor-in-Chief of Voice & Verse Poetry Magazine (聲韻詩刊). Beginning from September 2021, he will be an Assistant Professor at the University of Toronto.