茶 FIRST IMPRESSIONS

茶 REVIEW OF BOOKS & FILMS

Editor’s note: Aastha Uprety’s essay reads Jia Zhangke’s Still Life and Razan AlSalah’s A Stone’s Throw as twin elegies of engineered upheaval, where dams and pipelines reorder earth and memory. Through ruinous vistas and fractured archives, she traces displacement’s quiet aftershocks, exposing how state power and fossil capital sever bodies from ground, yet cannot still resistance.

[ESSAY] “Energies of Displacement: Transformation in Jia Zhangke’s Still Life and Razan AlSalah’s A Stone’s Throw” by Aastha Uprety

Click HERE to read all entries in Cha

on Jia Zhangke

❀ Jia Zhangke (director). Still Life, 2006. 108 min.

❀ Razan AlSalah (director), A Stone’s Throw, 2024. 40 min.

Sometimes the world around you changes irrevocably. Perhaps your ancestral town is submerged to power the future. Or your homeland becomes a site of resistance against an imperial world order.

Both films render the paradoxical experience of being uprooted from one’s familiar stretch of earth.

Jia Zhangke’s Still Life (2006) unfolds in a Chinese village soon to be submerged to accommodate the Three Gorges Dam, still the world’s largest generator of hydroelectric power. A Stone’s Throw (2024), directed by Palestinian filmmaker Razan AlSalah, juxtaposes the history of Britain’s critical fossil fuel infrastructure in the Middle East with contemporary offshore oil extraction in the Persian Gulf. By different means, both films render the paradoxical experience of being uprooted from one’s familiar stretch of earth, poised between power and powerlessness.

A man returns home after sixteen years in search of his former wife and daughter; a woman searches for her missing husband. Still Life situates these parallel narratives within the ongoing demolition of Fengjie, a riverside community on the banks of the Yangtze River, encircled by verdant hills. The film charts a measured crescendo of transformation: pickaxes striking brick in rhythmic succession, rubble engulfing streets and alleys, flood level markers appearing throughout the neighbourhood, residents crowding government offices in pursuit of assistance, partially demolished buildings standing like shed exoskeletons. Amid this upheaval, life persists, suffused with a quiet grief as one era yields to another. Thermoses keep tea warm in time worn kitchens; shirtless labourers slurp noodles during their lunch break; two lovers dance beneath an illuminated arch bridge spanning the Yangtze.

Han Sanming, portrayed by an actor of the same name who is also Zhangke’s real life cousin and a coal miner, arrives in Fengjie after years of toil in the mines, only to discover that the address he has carefully preserved on a scrap of paper refers to a neighbourhood now underwater. He can do little but wait for his wife to return from work in another village, wait to reunite with his daughter, and in the interim earn a living as a member of a demolition crew. His resignation, this enforced patience, stands in stark contrast to the fact that he purchased his wife sixteen years earlier, though she later fled of her own accord.

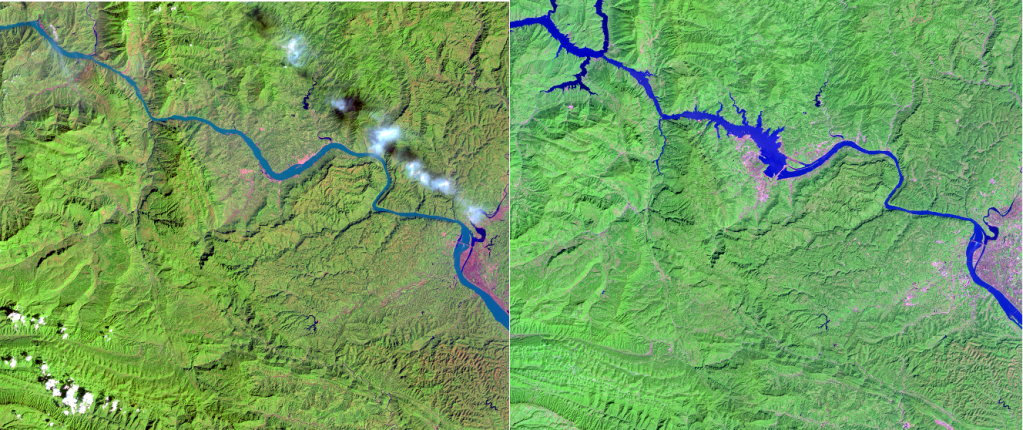

The Three Gorges Dam is such an immense structural achievement that it has measurably altered the earth’s rotation.

The Three Gorges Dam is such an immense structural achievement that it has measurably altered the earth’s rotation. The vast reservoir marginally slows the planet, lengthening each day by 0.06 microseconds. Like the oft repeated claim that the Great Wall can be “seen from space,” this fact serves as a convenient shorthand for China’s might.

When a state informs you that you will be relocated, that the land on which you were raised must be cleared to make way for a world altering dam, the sense of powerlessness is difficult to escape. Construction ultimately entailed the internal displacement of more than one million people. The characters in Still Life negotiate the turbulence of their intimate lives even as the very ground beneath them is irrevocably reshaped.

)

A Stone’s Throw is an experimental documentary that engages computer code, Google Earth first person perspective, animation, and archival footage and photographs. The film examines the labour organising and eventual anticolonial resistance of oil pipeline workers in Palestine during the 1930s. Petroleum transported through the Kirkuk Haifa pipeline originated in the oil fields of Iraq, passed to the refineries of Haifa, and was subsequently shipped across the Mediterranean to sustain the engine of the British Empire. As critical capitalist infrastructure, its maintenance depended upon the disciplining of labour.

Palestinian workers came to understand that the struggle exceeded the bounds of workplace conditions.

Yet Palestinian workers came to understand that the struggle exceeded the bounds of workplace conditions. As Zionist settlement expanded around them, the oil industry emerged as an instrument of colonisation. Over the course of several years in the 1930s, Palestinian rebels sabotaged the pipeline repeatedly. Its operations ultimately ceased in 1948.

Pipeline workers in Haifa, 1938. Via

The film then propels the viewer forward, through digital means, to Zirku Island. Zirku is a restricted offshore oil refinery situated off the coast of the United Arab Emirates. As the film relies upon Google reviews and satellite imagery to evoke the site, one infers that access is tightly controlled and exceedingly difficult.

On Zirku, oil industry labourers both reside and work under stringent surveillance and in austere conditions. The figure at the centre of the film, Amine, the filmmaker’s father, was born in Haifa, displaced to Beirut, and eventually employed at the Zirku refinery. There is scant discussion of resistance or labour agitation on the island, where organising is illegal in the United Arab Emirates. Yet when Amine sustains a workplace injury, recounted through an animated sequence reminiscent of a corporate safety video, he is hospitalised and, curiously, administered a medication typically prescribed to patients exhibiting violent behaviour. The implication is unsettling. Perhaps the authorities, mindful of the history of pipeline workers, sought to suppress the possibility of rebellion before it could take shape. The latent energy within a worker descended from a lineage of resistance is framed as a threat comparable to the energy stored in the oil extracted through his labour.

Through fragmentary glimpses of Amine’s migratory trajectory, A Stone’s Throw traces how the initial infrastructure of fossil fuel extraction expanded into a vast empire with roots extending across the Middle East. It evokes Andreas Malm’s Fossil Capital in dialogue with the incendiary premise of How to Blow Up a Pipeline. Amid its excavation of the region’s political and economic history, the film remains anchored in its central concern: the condition of uprootedness that defines the Palestinian diaspora. Poems and texts are interwoven throughout; among them is an English translation of the German poem “Der Wanderer” by Georg Philipp Schmidt, a piece that would not seem out of place on a title card in Still Life:

I wander silently and am somewhat unhappy / And my sighs always ask “where?” / In a ghostly breath it calls back to me / “There, where you are not, there is your happiness.”

)

Physical landscapes assume profound significance in both A Stone’s Throw and Still Life. A demolition worker asks Sanming whether he saw the Kuimen, or Qutang Pass, on his journey to the village, producing a ten RMB note bearing an illustration of the gorge as proof. Sanming replies that his own region appears on Chinese currency as well, and he retrieves a fifty RMB note depicting the Hukou Waterfall. It is among his earliest moments of connection in the film, a fleeting instance in which pride pierces the habitual stillness of his demeanour.

Still Life unfolds at an unhurried pace. Magnificent vistas recur throughout, interspersed with more modest scenes of quotidian activity, accompanied by title cards that read “cigarettes” and “candy.” The film invites sustained attention, urging the viewer to look closely, to observe, and to reflect upon what the characters themselves behold. Shot on location in Fengjie, it documents a landscape in the midst of tangible transformation. The rubble and partially demolished buildings that appear on screen are not constructed sets but elements of an actual site in flux. Yet the experience of viewing is far from straightforward. The high definition digital cinematography has prompted many viewers to question their screen settings upon pressing play. More conspicuously, abrupt incursions of magical realism punctuate the film’s 108 minute duration, occurring sparingly enough to provoke uncertainty about what has just transpired and whether it was imagined. Before settling into complacency, one must confront a disquieting question: how can transformation on such a scale, at such speed, be real?

A city with 2000 years of history was demolished in just two years.

Satellite imagery of the reservoirs created by the Three Gorges Dam on the Yangtze River. Left: 1993. Right: 2021. Via

A Stone’s Throw is more oblique still. It resists passive consumption and instead demands interpretation, assembling its argument through a collage of disparate sources and formal registers. Satellite imagery presents the region from an aerial vantage point, as though the viewer were an astronaut suspended in space, gazing upon vast deserts unmarked by visible borders. Archival photographs dissolve into unintelligible pixels when scrutinised too closely. Imagination becomes not an embellishment but a prerequisite. The film invokes the revolutionary writer Ghassan Kanafani, assassinated by Israel at the age of thirty six:

We need something more powerful than arms. Something bigger than material force. We need to unleash the imaginary, we need something irresistible, something that nuclear weapons cannot change. Something like a Palestinian child throwing a stone.

Palestine continues to resist colonisation, displacement, and mass death.

The film’s title denotes an action, a projectile set in motion. If Still Life functions as a form of eyewitness testimony, albeit tinged with the surreal, A Stone’s Throw operates as a cross examination, an active interrogation that forges connections between seemingly disparate fragments of a larger narrative. In light of current events, the story it recounts remains unresolved. Palestine continues to resist colonisation, displacement, and mass death. It is therefore fitting that the film centres upon oil, an extractive fossil fuel that must combust to become useful, a resource whose value is realised only through destruction.

Still Life, by contrast, tentatively entertains the possibility of renewal. The water that courses through the dam’s turbines generates power in a seemingly continuous cycle. The film raises a quiet question: might life, too, persist in altered form? In July 2025, the Chinese government commenced construction of the Medog hydropower station in Tibet, a dam projected to be three times as powerful as the Three Gorges.

Taken together, these two formally distinct films meditate upon the harnessing of the earth’s energy and the human cost of being severed from the ground beneath one’s feet.

A Stone’s Throw

How to cite: Uprety, Aastha. “Energies of Displacement: Transformation in Jia Zhangke’s Still Life and Razan AlSalah’sA Stone’s Throw.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 15 Feb. 2026, chajournal.com/2026/02/15/displacement.

Aastha Uprety is a writer and editor based in New York City. She considers herself a lifelong student of political economy and writes in a personal capacity here.