茶 FIRST IMPRESSIONS

茶 REVIEW OF BOOKS & FILMS

[REVIEW] “Karbala and the Ethics of Resistance: Premchand’s Vision of Communal Harmony” by Fathima M

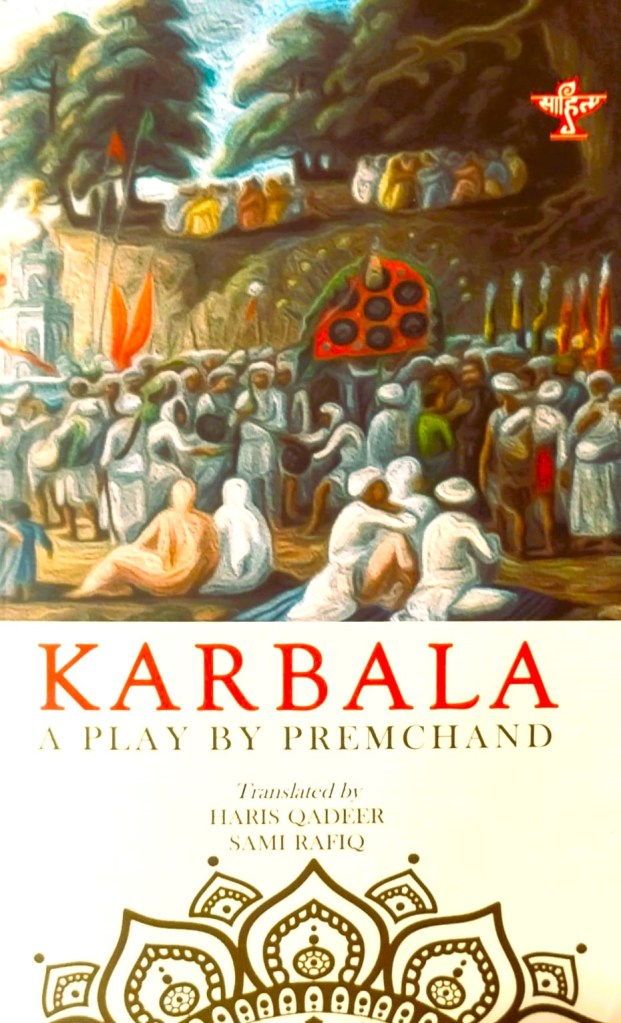

Premchand (author), Haris Qadeer and Sami Rafiq (translators), Karbala, Sahitya Akademi, 2023. 232 pgs.

The tragedy of Karbala signifies resistance and the defence of truth, and it resonates across the Eastern literary landscape in manifold ways. Within the South Asian literary sensibility, it constitutes an integral part of shared Islamic history and finds expression in diverse genres.

This social play was not only relevant to its own time, but is perhaps even more pertinent today.

This social play was not only relevant to its own time, but is perhaps even more pertinent today. Premchand (pictured), a well-known Indian writer, composed Karbala originally in Hindi and later self-translated it into Urdu. It was written at a moment when communal conflict in the country was visibly intensifying. Yet here was a writer who engaged with the “other” religion in a manner that expressed not merely inclusion, but a profound and selfless regard between Muslim and Hindu communities. The choice of drama as a genre is equally intriguing, as Premchand was primarily a short-story writer, and Karbala marked his first sustained engagement with dramatic form.

To reduce the play to something purely “religious” would be a reductive reading, yet to confine it to a single cultural framework would equally diminish its scope. In a world where nepotism, corruption, and conformism are pervasive, approaching the play as a critique of conformity renders it timeless. Premchand was foremost a storyteller and he remains so here. Through this play, he narrates a story in the service of communal harmony. It speaks to all, irrespective of religion, ethnicity, or any other marker of identity.

Premchand articulated his desire for harmony beyond religious and ethnic boundaries:

It is a sad and shameful fact that despite having lived with Muslims for so many centuries, we are still unacquainted with their history. One of the problems related to Hindu-Muslim animosity is that we, Hindus, are not familiar with the good qualities of the great personalities in Muslim history.

Karbala may be categorised as a social play set against a historical backdrop, in which the dramatist reworks both structure and narrative material. The tragedy at Karbala refers to the battle in which the Prophet’s grandson was martyred. In his confrontation with Yazeed, he was wronged and unjustly killed. Though he could have submitted to Yazeed, he refused to compromise truth and honour. Hussain was martyred because he stood for righteousness, and the story of his death has been told and retold in myriad forms.

The play unfolds in five acts and re-examines a significant historical event through a distinct lens. Writing from the context of India, Premchand adopts a critical outsider’s perspective to explore cross-cultural and cross-religious dialogue. He approaches religion through the prism of inclusion rather than through the binary opposition of “us” and “them”. Interfaith exchanges permeate the play. The central conflict is not between religious communities, but between good and evil.

The drama opens with Yazid demanding complete subservience following the Prophet’s death. He rejects any democratic mode of leadership and disregards the ethics of war. When Hussain and his followers refuse to submit, Yazid responds with vindictiveness and deceit, culminating in Hussain’s martyrdom. While Hussain’s martyrdom holds profound significance in Islamic history, its moral implications extend beyond a single tradition. Much as Paradise Lost by John Milton is shaped by its social undercurrents despite its Biblical framework, Karbala is interwoven with history, society, and narrative art.

The inclusion of Sahas Rai and his people constitutes a significant intervention. Their presence portrays both Islam and Hinduism as humane traditions, often manipulated as political instruments to incite unrest and division. Sahas Rai aids Hussain because he stands for truth, and Hussain, in turn, praises the culture of India. The communal harmony envisioned in the play offers hope, even if it appears distant within the climate of present-day India.

The significance of Karbala in Islamic history is immense. In literary representation, it symbolises the triumph of truth over falsehood and the imperative to remain ethical in moments of crisis. It embodies the courage to speak and act rightly, even in the face of ostracisation. Beyond its advocacy of communal harmony, the play also foregrounds the role of women. While women’s contributions are frequently marginalised in mainstream historiography, Premchand depicts the women in Hussain’s family as resolute and courageous, prepared to stand alongside men against tyranny. In doing so, he challenges the stereotype of Muslim women as passive or subjugated figures.

The persistence of violence suggests that, even as eras change, certain historical patterns endure.

The translation by Haris Qadeer and Sami Rafiq reads with clarity and fluency, and it arrives at a moment when communal tensions in India remain deeply troubling. Premchand wrote the play in 1924 under colonial rule, amid rising communal conflict. It is disquieting that such conflict persists. The persistence of violence suggests that, even as eras change, certain historical patterns endure. The translators draw upon their scholarly expertise to illuminate the play’s context, thereby enhancing its accessibility and readability. It is also heartening to see their names prominently acknowledged, reaffirming the significance of translation and the labour of translators.

How to cite: M. Fathima. “Karbala and the Ethics of Resistance: Premchand’s Vision of Communal Harmony.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 14 Feb. 2026, chajournal.com/2026/02/14/karbala.

Fathima M teaches English literature in a women’s college in Bangalore, India. She likes hoarding books and visiting empty parks. [Read all contributions by Fathima M.]