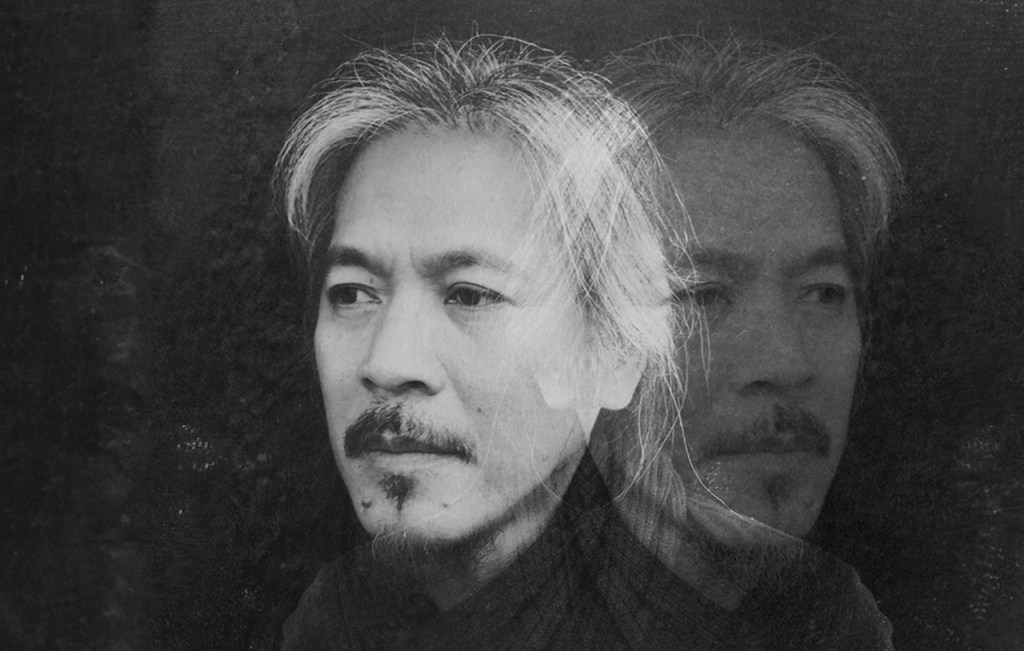

Editor’s note: In this reflective essay, Gutierrez Mangansakan II recounts acting on a film by Lav Diaz to examine how Mindanao shapes Diaz’s cinema. Blending personal observation with critical analysis, he argues that the director’s duration, restraint, and resistance to narrative closure arise from a regional history marked by violence, waiting, and unresolved pasts.

[ESSAY] “In Search of Mindanao in the films of Lav Diaz” by Gutierrez Mangansakan II

Back in 2013, I found myself acting for the first time in Lav Diaz’s film From What Is Before (2014). I had no ambition to become an “actor”; that was never the plan. Lav, as always, had other designs.

A still from From What Is Before

My intentions were far more modest. I wanted only to observe him at work. So I reached out to Liryc Dela Cruz, the production manager and a friend, and asked if I could tag along with Evelyn Vargas-Knaebel, the veteran actress playing a schoolteacher. The plan was to join her on the bus to the set in Abulug, Cagayan, far up in northern Luzon, twelve hours on the road from Manila.

Perry Dizon was there, too. He starred in my second film, Letters of Solitude (Cartas de la Soledad) (2011), and later turned up in Ryusuke Hamaguchi’s Drive My Car (2021). On Lav’s set he played Sito, a local man with a strange mix of menace and wounded loyalty, while simultaneously pulling double duty as the film’s production designer. It was a Lav Diaz film, after all; everyone wore at least two hats.

One afternoon, Liryc sent me a text. Lav wanted to cast me in the film.

I hesitated. I direct films; I do not act in them. I was happy enough hiding behind the camera, where I could pretend to be in charge without anyone really looking at me. Still, it was Lav Diaz. How could I say no to being directed by a legend? The lure of being directed by one of the world’s cinema greats was irresistible. I said yes, then immediately demanded to know more about the role. Liryc replied that I would be playing a school principal, the boss of Evelyn’s character.

The film takes place in 1972, at the height of the Marcos dictatorship. That meant not only that I had to grasp the psyche of people living under that regime at short notice, but also that I had to dress the part. Evelyn and I headed to the Anonas flea market in Quezon City, combing through racks of forgotten shirts and trousers, clothes that had lived through other lives, braving the smell of dust, sweat, and history.

The next afternoon, after hours at a laundry shop, we boarded the overnight bus from Manila to Abulug. Somewhere along that winding road, it struck me that Cagayan is Marcos country. Lav was making a film that called out the regime, right in its own backyard. It felt bold, perhaps even reckless. The excitement was mixed with a genuine sense of risk. I caught myself wondering whether I should text my sister a will, just in case. Would that even count as legal? Probably not. Still.

On that long ride, I tried to get into character. I was born in 1976, a few years after Marcos declared Martial Law. What was a school principal like back then? Why was I the principal, not Miss Acevedo, Evelyn’s character, who was clearly more senior?

These were questions of hierarchy, power, and gender, useful scaffolding for a character’s interior life. This was, after all, how I prepared my own actors. I assumed Lav’s methods must be similar.

I kept turning these questions over in my mind as we rolled past the rice fields of Bulacan and Tarlac, then cruised along the beaches of La Union and Ilocos. We finally pulled into Abulug at eight in the morning, just in time for breakfast and, honestly, a moment of existential reckoning.

Liryc picked us up from the bus terminal in a jeep. He had errands to run, kitchen supplies and items for production design. Seeing him calmed me. My nerves and excitement settled into something manageable. “Can I read the script?” I asked. He shot back, “What script?” During the drive through more rice fields, Liryc explained the situation. Lav does not really work with scripts, at least not in the conventional sense. He has an idea that lives in his head, developing and shifting as the shoot progresses.

The production headquarters turned out to be a mansion improbably planted in the middle of farmland. From the balcony, small houses were scattered across the plains and, beyond them, endless rice fields cut through with irrigation streams. It felt like a Marcos-era agricultural dream brought to life, orderly, productive, and quietly humming along.

That morning, I dropped my bag in a corner that someone indicated would be my sleeping area. I was given my first glimpse of Lav’s process. While we drank coffee and tried to orient ourselves in the house, Lav remained in his room. I heard guitar strumming for ten or fifteen minutes, followed by silence. Thirty minutes later, Hazel Orencio, actress, assistant director, and conduit of divine instruction, emerged carrying several sheets of paper, the script du jour. She distributed them to the actors scheduled to work that day. I received mine. My eyes scanned the page and landed on a single word: PRINCIPAL. Lav had written a short line for me. I could manage that.

Ten minutes later, Lav emerged and welcomed me to the set.

We were shaped by the same histories, the same myths, and the same sense of a place perpetually on the brink of transition.

I had first met Lav in Venice three years earlier, in 2010, when my film Bridal Quarter (Limbunan) (2010) premiered at the International Critics’ Week and he was serving on the Orizzonti jury. Our connection, however, extended beyond festivals and polite conversation. We both came from the province of Maguindanao, or the Cotabato Empire in Mindanao, southern Philippines, depending on whom you asked. Lav was born in Datu Paglas, spent his childhood there, and was friends with my cousins. I grew up in Pagalungan, about an hour from his town. We were shaped by the same histories, the same myths, and the same sense of a place perpetually on the brink of transition.

That afternoon, I performed my first scene as an actor.

)

When I asked Liryc if I could visit Lav Diaz’s film set in Abulug, I was not driven solely by the desire to watch a master at work. I wanted to know whether any trace of his Maguindanao, his Mindanao, had seeped into his cinema. This question had long preoccupied me. The advent of digital technology had opened the way for filmmaking to take place across the vast archipelago of the Philippines. The Singaporean film critic Philip Cheah coined the term “Regional New Wave Cinema” to describe this shift. Cinema was no longer a monopoly of the centre in Manila. Mindanao emerged as an active film hub, producing works that garnered accolades both in Manila and on the international festival circuit. In 2010, during the Cinemalaya Film Festival awards night, the Best Film trophy went to Sheron Dayoc’s Ways of the Sea, a film from Mindanao. The jury swiftly moved to canonise the moment, heralding the arrival of Mindanao cinema.

Yet, unlike other Mindanao filmmakers, Sherad Anthony Sanchez (Sewers, 2008), Arnel Mardoquio (The Journey of Stars into the Dark Night, 2012), Bagane Fiola (Wailings in the Forest, 2016), and myself, whose narratives are unmistakably rooted in the region, whose films deliberately foreground Islamised Moro and indigenous Lumad characters, and whose work openly grapples with Mindanao’s turbulent histories and unhealed wounds, Lav’s oeuvre appeared to orbit elsewhere. His landscapes were different, his geographies drawn away from home. Consider Death in the Land of Encantos (2007), set across nine hours in the battered fields of Bicol after Typhoon Reming, or Melancholia (2008), which wanders through Manila, tracing political despair and spiritual fatigue across the city. None of his films, at least on the surface, returned to Mindanao. And yet I kept asking myself whether one ever truly leaves the place that shaped them.

The next morning, I woke early, well rested. I hurried to the balcony and watched the village as the sun climbed through a thin veil of cloud. Farmers mounted their kuliglig, improvised motor vehicles combining a tractor with a two wheeled trailer, and ventured into the fields, their engines sputtering like insects clearing their throats. Women were already deep in negotiations with fish vendors, their voices sharp and practised, honed by years of repetition. The entire place was alive and in motion. Down in the kitchen, the day was already underway. I joined the others, exchanging greetings. Perry was awake. So was Liryc. I caught the smell of garlic and frying eggs, but my body, faithful to ritual, demanded coffee first. I poured myself a mug.

“How was your first day as an actor?” Liryc asked.

I laughed and glanced down at my toenails, still streaked with mud from the previous day.

I laughed and glanced down at my toenails, still streaked with mud from the previous day. My baptism as an actor involved a scene in which Miss Acevedo and I visited Sito’s house because his nephew had been skipping school. The path leading there was a muddy road hemmed in by tall grass. When Lav blocked the scene, he wanted us to walk straight down the middle. Instinctively, I sensed that Lav was up to something. I took off my shoes and walked carefully along the edge, avoiding the deepest part of the road. I could have endured the mud, my height gave me that advantage, but Evelyn would have been swallowed whole. Lav has a skewed sense of humour, but not, I suspect, a murderous one.

“I’m looking forward to today’s scenes,” I said, keeping a straight face.

After breakfast, Lav’s routine resumed. He shut himself away, strumming a guitar softly, then silence. About half an hour later, Hazel emerged with the script for the day. Everyone received a page. I scanned mine and felt my heart sink. There was no easy one liner this time. Instead, I was faced with a formidable stretch of dialogue, and worse still, the scene was with Evelyn and Perry, actors of depth and discipline.

I practised my lines repeatedly. The scene involved Miss Acevedo and the school principal visiting Sito once again. That afternoon, inside a makeshift house standing alone in the middle of a rice field and adorned with large bamboo fishing implements, Lav, who was also serving as cinematographer, set up the minimal lighting required. I muttered my lines under my breath like incantations, as though survival depended on exact phrasing.

The scene began shakily, then found its rhythm. In my head, I estimated it would run for ten minutes, perhaps less, one of Lav’s signature long takes. What made it more challenging was anticipating the cut. Lav never cut when logic suggested that he would. He lingered, and so we lingered too, guided by an unspoken agreement, continuing with small gestures and invented business while waiting for his signal. We did fifteen takes. Lav never explained why. He never pointed out what was wrong. We simply did it again and again.

That night, after dinner, Lav and I sat at a garden table and talked about his years in Maguindanao. I could see how he drifted through those memories, lingering in Datu Paglas. He spoke about people, places, old rumours, and half remembered myths. When someone else tried to join the conversation, Lav switched from Tagalog to our Maguindanaon language, quietly closing us off from the rest. He brought up characters from his early films and said that they were drawn from real people he had known while growing up. He listed names that I recognised and explained how these individuals had inspired some of his film characters. He also spoke of a mysterious bird, “masla a papanok”, large, dark, and ominous, believed to foretell Martial Law, a myth he had learned as a young boy.

In that moment, I found the answer I had been seeking. Lav may not have made films that are overtly Mindanao in subject, but his imagination, and his method, are tied to the landscape of his childhood.

Even when his films are not explicitly set in Mindanao, the region shapes his worldview.

Composite satellite image of Mindanao captured by Sentinel-2 in 2019. Via

Lav’s Mindanao background is fundamental to his cinema. It does not function as local colour or autobiographical detail, as mine often does, but as an ethical position, a historical consciousness, and a way of seeing time, violence, and power. Even when his films are not explicitly set in Mindanao, the region shapes his worldview, his cinematic grammar, and his entire approach to filmmaking.

Mindanao is the Philippines’ most persistently colonised and militarised region, first by Spain, then by the United States, and later through Manila centred nation building projects that dispossessed the Islamised Moro and indigenous Lumad peoples. This long history of betrayal, land theft, and state violence informs Lav’s sustained engagement with historical injustice.

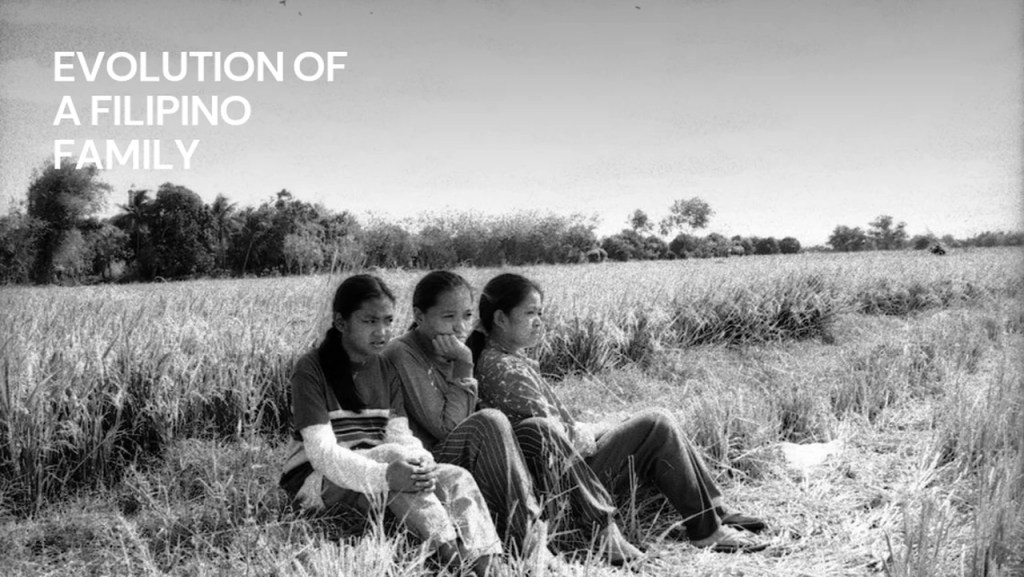

In films such as Evolution of a Filipino Family (2005) and Florentina Hubaldo, CTE (2012), history is not a backdrop but a slow, grinding force that deforms lives across generations. This sensibility resonates deeply with the experience of Mindanao, where violence is cyclical and unresolved, and where the present is continually haunted by unfinished wars.

Lav’s cinema refuses closure because Mindanao’s history itself has never been granted resolution.

Lav’s cinema refuses closure because Mindanao’s history itself has never been granted resolution. Coming from Mindanao places him outside the dominant Tagalog Manila cultural axis that has shaped Filipino cinema for a century. His work resists the polish, speed, and narrative efficiency associated with Manila based commercial filmmaking, even when his films employ the Tagalog language. This distance manifests formally in his extreme durations, his rejection of spectacle, his non psychologised characters, and his emphasis on collective suffering rather than individual triumph.

This is a peripheral gaze, a way of looking from the margins inward, suspicious of national myths and elite narratives. His films dismantle the idea of a unified Filipino identity by foregrounding fragmentation, silence, and absence.

Life in Mindanao, particularly rural Mindanao, where Lav and I both come from, is structured by waiting, for harvests, for peace, for ceasefires, for justice. In this sense, I too have inherited Lav’s durational cinema, which mirrors this lived temporality. Our long takes are not stylistic indulgences. They approximate the slowness of agrarian life, the weight of historical memory, and the exhaustion produced by perpetual instability.

Sitting through a five hour film may feel tedious, but viewers are made to endure rather than merely observe, echoing the long patience demanded of communities in Mindanao that have lived through decades of conflict and neglect.

Mindanao is also a site of plural belief systems, Islam, which is my faith; Christianity, which is Lav’s; and indigenous cosmologies that are still awaiting their filmmaker, coexisting in a state of tension.

Weeks later, after I had returned to General Santos City, Liryc messaged me. Lav wanted to expand my character. It was Christmas, and they were shooting through the holidays. I had only a few scenes in the film, and the prospect of doing more thrilled me, but prior commitments forced me to decline. Another message soon followed. Liryc was asking for the contact details of the actress Bambi Beltran, whom Perry had suggested for a role Lav wished to explore. Back in my living room in Mindanao, I imagined Lav once again in his room, the guitar, the silence, the mind of a genius at work.

A year later, the answer I had sought during my time with Lav finally revealed itself. From What Is Before (Mula sa Kung Ano ang Noon) opens with a procession of the sick and the desperate moving across rolling hills in an unnamed town in Mindanao. A crowd gathers. A woman announces the arrival of Rahma, the healer, played by Bambi. A ritual unfolds, accompanied by the Maguindanaon music that Lav and I grew up with, revealing faith, desperation, and ancient memory. It is Lav’s first overtly Mindanao film.

Lav had finally come home.

How to cite: Mangansakan, Gutierrez II. “In Search of Mindanao in the films of Lav Diaz.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, Feb. 2026, chajournal.com/2026/02/09/lav-diaz.

Gutierrez Mangansakan II is a filmmaker and writer. He has published a collection of essays, Archipelago of Stars, and a collection of short stories, Closing Party and Other Stories, and has edited three anthologies on Bangsamoro literature. He was a writer in residence at the University of Iowa’s International Writing Program in 2008, and a fellow of the University of the Philippines National Writers Workshop in 2015. He lives in General Santos City, in the southern Philippines, with his ten cats and a beagle. [All contributions by Gutierrez Mangansakan II.]