[SUNDANCE 2026] “Visions of a Future Self: Kogonada’s zi” by Nirris Nagendrarajah

Kogonada (director), zi, 2025. 199 min.

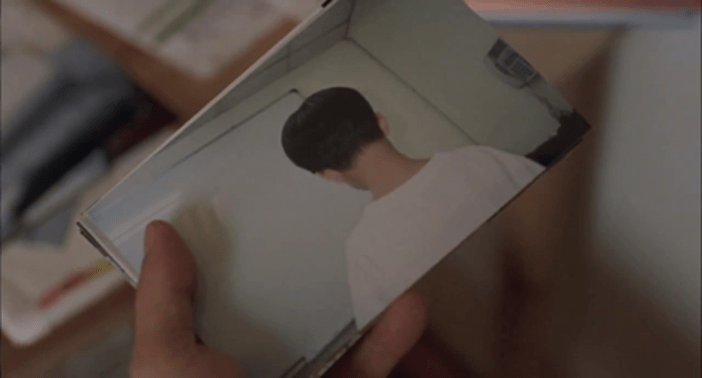

In cinema, whenever I see a shot of the back of a character’s head, I think of a scene from Edward Yang’s Yi Yi (2000), when the young Yang-Yang (Jonathan Chang), who will later go on to take photographs of faceless heads, asks his father about the impossibility of seeing the world through another’s perspective. “Can we only know half of the truth,” he asks. His father does not compute. “I can only see what’s in front, not what’s behind. So I can only know half the truth, right?” It is the kind of distilled, dimension-shifting wisdom that lands with a subtle force, and whose residue lingers forever after. That zi, the new film from director, editor, and essayist Kogonada, who has often cited Yang as a formative influence, opens with the back of its titular protagonist’s head, which comes as no surprise.

A still from Edward Yang’s Yi Yi

Having recently returned to Hong Kong, Zi Wong (a terrifically disconsolate Michelle Mao) is a violinist awaiting a possible cancer diagnosis, who experiences destabilising and disorienting visions over the course of a long day’s journey that stretches into the night. Early on, she visits the graves of her parents and laments not having taken the time to remember their faces while they were alive, now gripped by the fear of forgetting them. “All I can picture is the back of your heads,” she says tearfully.

Throughout the film, Kogonada’s brisk, restless editing style replicates the uncontrollable fluctuations of Zi’s mind: stock variations, exposures, flickers, flash-forewords, and flashbacks. The film opens in a kind of sensory free fall, as if cast under a spell before it has time to settle. That instability reflects the film’s semi-improvisational production as well. Like Hong Sang-soo, it was written and shot in secret with three actors and a small crew over a brief period in October, before premiering at Sundance in January. When the film finally exhales, it settles into a cool, dreamy register, shaped by Benjamin Loeb’s grainy, gliding cinematography and a score drawn from the late Ryuichi Sakamoto’s oeuvre, including selections from Opus (2023), composed with the knowledge of his imminent death. It is music that feels like a dispatch from liminal space, the precipice where Zi wrestles not only with morality, but with her existence.

A still from Agnes Varda’s Cléo 5 to 7

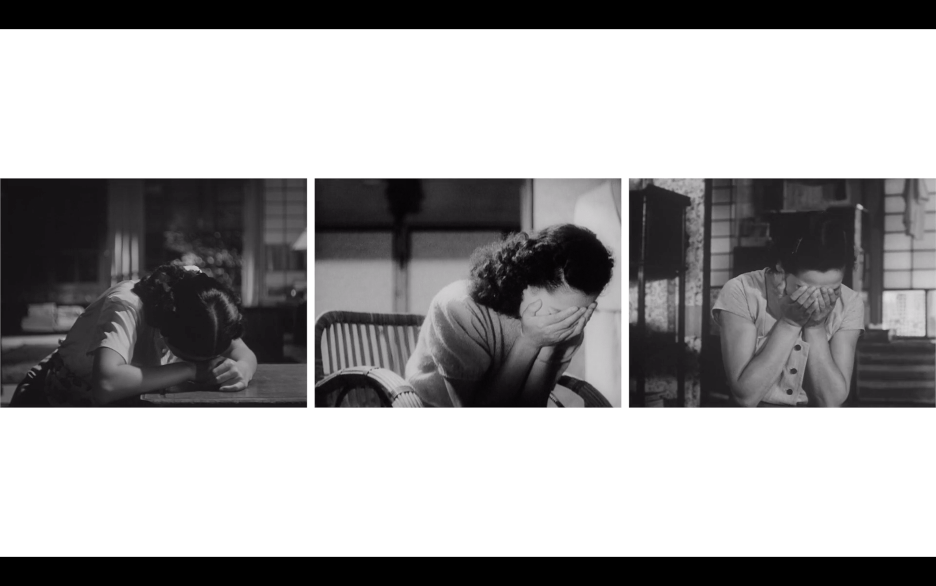

Zi’s frame of mind, waiting to learn whether you are going to live or die from cancer, recalls Agnès Varda’s Cléo 5 to 7 (1962), a reference made explicit when Zi flees from her new friends Min (an enigmatic Jin Ha) and Elle (a grating Haley Lu Richardson), and gravitates towards an underground tunnel, inside which a violinist plays Michel Legrand’s “Sans Toi.” The references do not stop there. As he has previously done in both After Yang (2021) and Columbus (2017), the film contains the “pillow shots” that draw on the influence of Yasujiro Ozu, an influence that, for those who remember his 2017 video essay Way of Ozu, Kogonada is deeply versed in. Just before she meets Elle, when she becomes overwhelmed, Zi bursts into tears and instinctively covers her face with her hands, an image that immediately recalls the triptych of the actress Setsuko Hara’s weeping, and falls into line with the continuum of that cinematic gesture.

A still from Kogonada’s Way of Ozu

zi is a spattering of homages, pleasurable to identify, but subtle acts of resistance are embedded within it too. When the newly formed trio roam the city streets, settle into an outdoor karaoke spot, and each begin to sing, with Zi choosing Faye Wong’s “Wishing We Last Forever,” one might recall the scene in Sofia Coppola’s Lost in Translation (2003). This association corresponds with the blonde wig that Elle wears for most of the film, a mask that causes her to feel anonymous, as though her real self is not being seen.

Later, however, when they are in the back of a taxi, instead of placing the camera outside the car, as Coppola does, herself referencing the style of Wong Kar-wai, to observe the reflection of lights transposed on the protagonist’s face, Kogonada focuses instead on the potential of the rear view mirror, where the women’s faces are consumed by darkness. He resists fetishising the metropolis, which, in its absence of interaction with any other characters, feels private and insular, much like Neo Sora’s Happyend (2024): otherworldly, a space where the possibility of a doppelgänger is not an absurd manifestation, and borderless too, as hinted at when the women briefly kiss. Here, the edges of all the variables have been eroded.

She confesses to the sea, the Kowloon ferry gliding behind her, perpetually in transit.

Zi repeatedly flees moments of perceived exclusion, running from former flames only to find herself crying alone in crowds, her private devastation framed by public spectacle. A fireworks display casts her grief in sublime light. Bridges recur as visual motifs, with characters framed, or perhaps enclosed, by Hong Kong’s dense architecture, dwarfed by high rises and the city’s relentless vibrancy. Across the film’s 99 minutes, Zi moves from a state of abandonment to an understanding that survival arises from relationality. “I don’t want to be alone anymore,” she confesses to the sea, the Kowloon ferry gliding behind her, perpetually in transit. The word she uses to describe her condition is “untethered,” a sense of time being out of joint, of facing irreality.

A still from Kogonada’s zi

For Zi, life itself has become a misunderstanding, without anchors in the world or a hold on who she is.

The added magic of zi lies in its details, from the books on Min’s shelf, The Future of the Brain (2024) and Zahl Zalloua’s Being Posthuman (2021), to Zi’s necklace, which shifts from a circular jade pendant to a stone one engraved with 自由, which translates to freedom or liberty, though the film is more concerned with the former than the latter, and the red scarf that signifies her future self, traded in for the red bag and shoes of the present tense. “Am I in the present or the past,” she asks. “For you it’s always the past,” Min replies. For Zi, life itself has become a misunderstanding, without anchors in the world or a hold on who she is. She drifts with the glimmer of hope that light will break through the cracks at any moment.

The film’s rapid-fire frequency possesses a freedom that the meticulously drawn Columbus lacked, while furthering the creative liberty that forged After Yang. Several critics have framed zi as a response to Kogonada’s recent critical and commercial failure A Big Bold Beautiful Journey (2025), calling it “experimental” and “thin”, yet for me it is a natural addition to his practice, a resurfacing of the genius of the essayist who created emotionally resonant moments through the curation and juxtaposition of visual relations across time. Like Zi, Kogonada remains preoccupied with the partiality of perception, its grey areas, the half-truths that haunt us before they might enchant us, becoming another way of carrying on.

zi comes full circle, then, landing at a juncture that is the anterior, and interior, of the past. It is like watching the face of Janus, but inverted, turned towards itself, a one and a two.

By the film’s end, the gap between the visions narrows with the assistance of Elle and an older version of her, played by Haley Lu Richardson’s real-life mother, Valerie Richardson. zi withholds clarification of its central ambiguity, the exact nature of Zi’s condition, but the specifics matter less than the inspiration it produces in the mind of its creator and the attuned audience member, familiar with the kind of laugh that suddenly tips over into weeping. The film shifts back into the 16mm stock from the start, except now we have made it to the other side of the back of the head, Zi’s radiant and exposed face. zi comes full circle, then, landing at a juncture that is the anterior, and interior, of the past. It is like watching the face of Janus, but inverted, turned towards itself, a one and a two.

How to cite: Nagendrarajan, Nirris and Makoto Nagahisa. “Visions of a Future Self: Kogonada’s zi.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 4 Feb. 2026, chajournal.com/2026/02/04/zi.

Nirris Nagendrarajah is a writer and culture critic from Toronto. In addition to Metatron Press, his work has appeared in MUBI Notebook, Little White Lies, The Film Stage, Ricepaper, Notch, Polyester, Intermission, Ludwigvan, and In the Mood Magazine. He is currently part of Neworld Theatre’s Page Turn program and at work on a novel. [All contributions by Nirris Nagendrarajah.]