Editor’s note: Zalman S. Davis places Xuân Diệu and Huy Cận within Vietnamese literary history shaped by Confucian ethics, French colonial modernity, and revolutionary discipline. The essay reads Thơ Mới poetry as a space where male intimacy could appear through ambiguity and restraint. Xuân Diệu’s sensuous lyricism and Huy Cận’s melancholic reserve express modern subjectivity inflected by suppressed queer desire. Their partnership influenced Vietnamese modernist poetics, later obscured by socialist historiography yet central to understanding twentieth-century transformations of intimacy, authorship, and lyric voice.

[ESSAY] “Between Confession and Restraint: Queer Intimacy and the Making of Vietnamese Modernist Lyricism in Xuân Diệu and Huy Cận” by Zalman S. Davis

Huy Cận and Xuân Diệu

The relationship between Xuân Diệu (1916-1985) and Huy Cận (1919-2005) holds a unique significance in Vietnamese literary history. Both poets were prominent figures in the Thơ Mới (“New Poetry”) movement, and there has been sustained speculation regarding the romantic dimensions of their friendship. Emerging in the 1930s, the Thơ Mới movement marked Vietnam’s first prolonged engagement with Western-influenced lyric subjectivity, signalling a departure from traditional Confucian collective poetics.

Within this modernist framework, the works of Xuân Diệu and Huy Cận embody two complementary temperaments: Xuân Diệu’s sensuous celebration of love and impermanence, set against Huy Cận’s introspective melancholy and metaphysical detachment. Their shared literary presence, cohabitation, and the emotional reciprocity evident in their poetry have led some scholars and biographers to interpret their relationship through the lens of same-sex desire. Although definitive documentary evidence of a sexual or romantic relationship is lacking, the convergence of textual analysis, personal testimony, and socio-historical context provides a valuable framework for understanding the construction of subjectivity, intimacy, and masculinity in early twentieth-century Vietnamese literature.

)

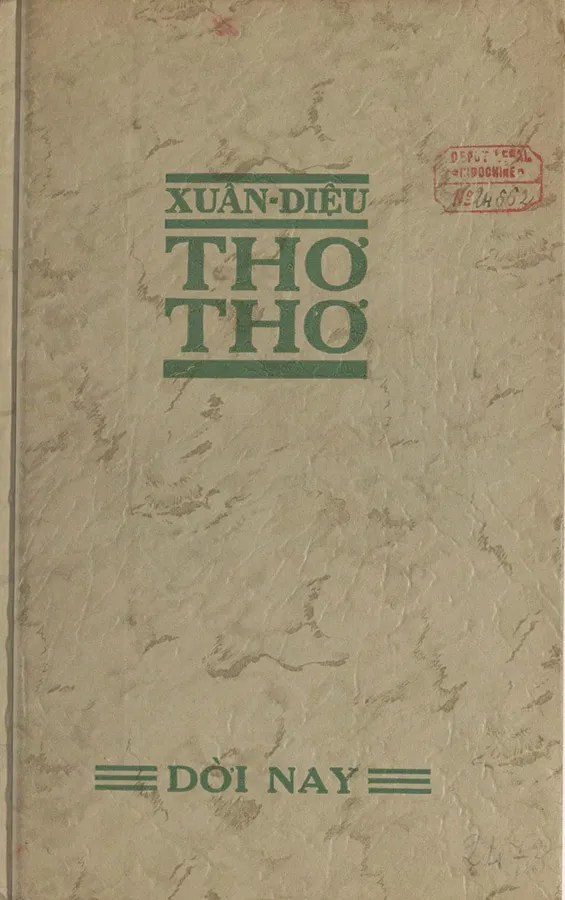

Xuân Diệu’s inaugural collection, Thơ thơ (1938), exemplifies the Thơ Mới movement’s departure from classical restraint. His poetry centres on the individual as a sensate being who experiences time, love, and nature as interwoven phenomena. The speaker’s emotional intensity, often bordering on eroticism, was unprecedented in Vietnamese poetry of the period. Love is presented not as a moral obligation or familial duty, but as a bodily and existential necessity. Notably, the gender of the beloved in Xuân Diệu’s poems remains largely indeterminate. The recurrent use of the pronoun em, which in Vietnamese can denote either a younger male or female lover, permits both inclusivity and ambiguity. This grammatical uncertainty, combined with a consistent avoidance of heteronormative imagery, suggests that Xuân Diệu’s articulation of desire operates within carefully coded boundaries. His renowned poem “Tình trai” (“Male Love”) constitutes the most explicit textual indication of homosexual sensibility, referencing the relationship between the French poets Rimbaud and Verlaine as an unmistakable allusion to same-sex passion, rendered in empathetic terms. In colonial Vietnam, where public discourse on homosexuality was virtually non-existent, such a reference amounts to a rare act of self-affirmation.

Under French colonial rule, Vietnamese intellectuals absorbed European romantic and symbolist idioms.

The reception of “Tình trai” within the literary landscape of the late 1930s reveals a nuanced negotiation between admiration and discomfort. Critics praised Xuân Diệu’s technical mastery while frequently sidestepping the gender implications embedded in his language. His lyrical intensity was often described as “Western”, a euphemism that acknowledged modernity while simultaneously displacing potential moral unease. This interpretive reticence reflects a broader cultural condition. Under French colonial rule, Vietnamese intellectuals absorbed European romantic and symbolist idioms while remaining deeply embedded in Confucian social norms. Expressions of bodily or erotic emotion, particularly same-sex emotion, could be aesthetically admired yet remained socially unacknowledged.

It was within this context that Xuân Diệu formed a close relationship with Huy Cận. Both poets were students at the Lycée Khải Định, later Quốc học Huế, and subsequently shared accommodation in Hanoi during the early stages of their literary careers. Numerous contemporaries, including members of the Tự Lực Văn Đoàn (Self-Strengthening Literary Group), remarked upon their inseparability. Publicly, their bond was characterised as one of artistic solidarity and intellectual kinship. However, their domestic arrangement, sustained emotional reliance, and later recollections from acquaintances such as Tô Hoài have prompted scholars to interpret their partnership as exceeding mere collegiality. In memoirs written decades later, Tô Hoài recounts an incident in which Xuân Diệu was reprimanded by revolutionary authorities in Việt Bắc for what he described as tình trai, a confession of homosexual love. Xuân Diệu’s visibly distressed response suggests that his orientation was known among his peers, yet subject to suppression under socialist moral norms.

The extent of Huy Cận’s involvement in, or response to, this aspect of their relationship remains less well documented. He later married and assumed prominent cultural roles within the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, positions that required conformity to state ideals of family and virtue. Nevertheless, textual evidence in his poetry indicates a lasting emotional connection to Xuân Diệu. His elegy “Viếng mộ Diệu” (“Visiting Diệu’s Grave”) commemorates their shared history in language that is strikingly intimate for a male friendship. The poem’s reflection, “Huy, Xuân, one meeting of souls, half a century not enough for mutual understanding”, invokes the concept of tri âm (soul-mate), a term typically reserved for idealised romantic or aesthetic partnerships. The depth of attachment implied by this phrasing supports an interpretation of their relationship as emotionally, and potentially erotically, charged, even if never explicitly acknowledged.

)

To contextualise this within the broader spectrum of Vietnamese literary culture, it is essential to examine how male intimacy was understood within Confucian and colonial frameworks. Pre-modern Vietnamese literature, shaped by Chinese traditions, contains numerous depictions of close male friendships that contemporary scholars might characterise as homosocial rather than homosexual. These relationships were idealised as bonds of loyalty and shared cultivation, rather than as expressions of erotic attachment. The Thơ Mới generation, however, internalised Western notions of the individualised lover and the secular love poem. Within this new paradigm, expressions of profound affection between men acquired a distinct semantic resonance. When Xuân Diệu wrote of the urgency of youth and the fear of isolation, or when Huy Cận articulated metaphysical loneliness, such sentiments could readily intersect with experiences of same-sex desire, albeit constrained by social silence.

The forbidden nature of his desire intensifies the temporal anxiety that permeates his verse.

The intersection of sexuality and modernism in their work therefore warrants systematic examination. Xuân Diệu’s romanticism, often interpreted as universal humanism, can be more precisely understood as a poetics of sublimated queer desire. His emphasis on immediacy, expressed in the injunction “Hurry to love, for time passes”, functions not merely as an existential assertion but as a response to prohibition. The forbidden nature of his desire intensifies the temporal anxiety that permeates his verse. By contrast, Huy Cận’s early collection Lửa thiêng (“Sacred Fire”, 1940) constructs a poetics of absence and distance, with speakers frequently positioned apart from their objects of longing, observing rather than engaging, yearning for connection while anticipating loss. The dialogic interplay between Xuân Diệu’s sensuous immediacy and Huy Cận’s restrained withdrawal generates a dialectical tension that became central to Vietnamese modernist lyricism.

Following the revolutionary period after 1945, the trajectories of the two poets diverged. Huy Cận adapted his voice to socialist realism, concentrating on themes of labour, soldiery, and national solidarity. Xuân Diệu, while participating in state literary institutions, continued to emphasise love and personal emotion, albeit reframed within the rhetoric of collective or national affection. Archival materials and subsequent criticism suggest that he struggled to reconcile his private identity with the public expectations of revolutionary culture. His brief marriage in the 1950s to the filmmaker Bạch Diệp, followed by divorce, may be interpreted as a social accommodation rather than evidence of heterosexual orientation. From this point onwards, his sexuality effectively disappeared from official discourse, replaced by the sanctioned image of the “poet of love”.

This erasure reflects a broader historiographical pattern. Vietnamese literary scholarship after 1954 has tended to prioritise political allegiance and moral exemplarity, frequently avoiding sustained engagement with sexuality, particularly non-normative sexuality. The recovery of Xuân Diệu’s queer dimension has emerged only in recent years, as scholars both within and beyond Vietnam have revisited Thơ Mới through the lenses of gender and queer theory. Online archives and independent critics have begun to recognise the importance of “Tình trai” as one of the earliest Vietnamese poems to acknowledge same-sex love. Mainstream academic institutions, however, continue to frame Xuân Diệu’s eroticism in neutral or universalist terms, largely sidestepping explicit discussion of homosexuality.

)

Huy Cận’s position is even more complex. As a prominent figure within the cultural establishment, he cultivated a public persona aligned with socialist ideals. Nevertheless, his late-life reflections on Xuân Diệu convey a persistent emotional attachment. The closeness of the two men during the 1930s and 1940s, their shared aesthetic vocabulary, and the absence of comparable relationships elsewhere in their biographies all point to a profound bond that shaped their creative development. To interpret this bond solely through heteronormative categories of friendship risks overlooking the nuanced forms of intimacy available to queer individuals in both pre-revolutionary and post-revolutionary Vietnam.

Methodologically, the absence of direct documentary evidence necessitates a reading practice attentive to silence, ambiguity, and textual displacement. Queer theory’s emphasis on the unsaid and the performative enables a more nuanced understanding of the relationship between Xuân Diệu and Huy Cận, as articulated by Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick in her formulation of the “epistemology of the closet”, in which identity operates through partial disclosure. Within this framework, the gender-neutral beloved in Xuân Diệu’s poetry and the mournful abstraction characteristic of Huy Cận’s early verse may be understood as literary closets, forms that simultaneously reveal and conceal. Their cohabitation, the emotional lexicon of their poetry, and retrospective testimonies from contemporaries together constitute a triangulated body of evidence sufficient to sustain scholarly inquiry, even in the absence of confessional documentation.

Interpreting their connection through this lens also enriches the historiography of Vietnamese modernism. The Thơ Mới movement’s embrace of individual emotion has often been characterised as a symptom of Westernisation. It may equally be understood, however, as an indirect means of articulating suppressed affect, including same-sex desire. Xuân Diệu’s queerness thus emerges not as a marginal biographical detail but as a formative force in the creation of a modern Vietnamese lyric subject. The fusion of classical metaphor with Western sensibility in his poetry generates a language of intimacy capable of accommodating non-normative feeling while remaining culturally legible. Huy Cận’s participation in this linguistic and emotional experimentation illustrates how male friendship could function as a socially acceptable surface for deeper affective exchange.

The implications of this reading extend beyond biographical interpretation. Recognising the queer subtext in the works of Xuân Diệu and Huy Cận complicates nationalist narratives that later subsumed the Thơ Mới generation within a teleological account of revolution and moral renewal. Their poetry reminds us that modern Vietnamese literature did not arise solely from political awakening but also from the negotiation of private desire within restrictive cultural frameworks. The possibility of a romantic or sexual relationship between the two poets, whether fully realised or not, exemplifies this negotiation, situating queerness not as a Western import but as an indigenous experience shaped by colonial modernity and socialist morality.

The partnership between Xuân Diệu and Huy Cận should be understood as a complex intersection of aesthetics, affect, and social constraint. The available poetic, testimonial, and contextual evidence supports an interpretation of their relationship as emotionally, and potentially erotically, intimate, even if never publicly acknowledged. This intimacy significantly shaped the emotional vocabulary of Vietnamese modernism, contributing to the characteristic tension within the Thơ Mới movement between confession and restraint. Recognising the queer dimension of this history does not impose anachronistic identity categories but instead seeks to recover the full range of human emotion that animated early twentieth-century Vietnamese poetry. Examining Xuân Diệu and Huy Cận through this perspective allows literary scholarship to move beyond moralised biography towards a more inclusive understanding of how love, secrecy, and artistic collaboration converged in the formation of Vietnam’s modern literary identity.

The home in old Quarter Hanoi where Huy Cận and Xuân Diệu lived together

Photograph by Zalman S. Davis

How to cite: Davis, Zalman S. “Between Confession and Restraint: Queer Intimacy and the Making of Vietnamese Modernist Lyricism in Xuân Diệu and Huy Cận.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 3 Feb. 2026, chajournal.com/2026/02/03/vietnamese-lyricism.

Zalman S. Davis is active in South African literature, working as a publisher, literary curator, editor, and critic. As the founder of Minimal Press, Davis has established a platform that champions diverse voices across genres and languages, with an emphasis on quality storytelling and literary merit. He curates several literary awards, including the Ingrid Jonker: L’Art Poétique Prize for Poetry, the Chris Barnard Prize for Short Stories, and the Diana Ferrus Prize for Poetry in Afrikaans Dialects. These awards have drawing entries from across South Africa and internationally. Beyond his curatorial endeavours, Davis has contributed as an editor, overseeing the publication of various anthologies and literary collections, and ensuring that both emerging and established writers are afforded a platform to share their work. His dedication to literature and language was recognised in 2020, when he received the Koker Toekenning Award for his contributions to Afrikaans and South African letters. Davis’s commitment to the literary arts extends to his role as a critic, where his insights and analyses engage with contemporary South African writing. His work continues to enrich the cultural fabric of the nation—standing as a testament to the enduring power of storytelling across borders and tongues. [All contributions by Zalman S. Davis.]