Editor’s note: Chris Sullivan reflects on an unexploded wartime bomb in Hong Kong, observed from Amsterdam, using the incident to consider urban memory, historical residue, and the quiet persistence of past violence.

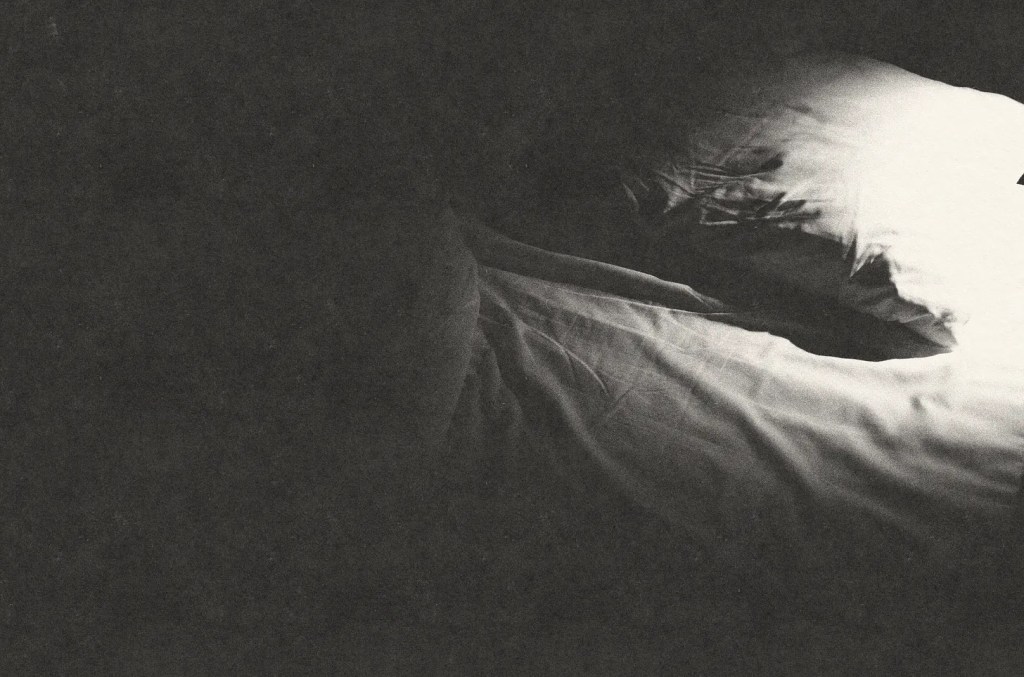

[ESSAY] “Disarming a Ghost” by Chris Sullivan

Hong Kong, 2025

I was in Amsterdam, sitting in the spill of tables from a noisy bar, settling into a round of drinks with my partner. It had rained over the past few days, but this evening was clear. The sun made a slow retreat, and the sky held its blue into the night.

Nearby, three boys were atop a bridge, dredging the canal with heavy magnets. When a bicycle frame slowly emerged from their lines, streaming with sediment, they painstakingly worked it towards the bank to the applause of the watching crowd.

Nine thousand kilometres away in Hong Kong, an emergency response unit was disarming a recently unburied ghost across the street from our apartment. We watched it unfold over a phone screen, glasses of Hertog Jan in hand.

Amsterdam, 2025

The ghost was a 450-kilogram (1,000-pound) aerial bomb, dropped by the U.S. Army in 1945 on then Japanese-occupied Hong Kong. When the bombardier looked down from around 16,000 feet, the altitude specified for the 528th Squadron, they were not looking at the neighbourhood as it stands today. According to field orders, their primary target was “Shipping at HONGKONG.” The crosshairs likely settled on the Taikoo Docks and its cranes and slipways. While the raid’s payload of 144 bombs presumably found their targets, our recently surfaced stray seems to have drifted off course towards the nearby Taikoo Sugar Refinery.

In the eighty years since this lunchtime raid, the city has pushed back the coastline and filled in the industrial sites. The bomb had been sitting there the whole time. It waited through the surrender of Japan, the handover of “97,” and the signing of my partner’s lease. It waited eighty years for a construction crew to wake it up.

Amsterdam, 2025

In Amsterdam, the group of boys left their salvaged bicycle under a mother’s supervision, then trooped back to the bridge to cast their lines again.

On the phone screen, the view was unstable. The familiar scenes of our neighbourhood pixelated into blotchy low-resolution video: the familiar pink uniforms of the downstairs cha chaan teng workers, and the neighbours I saw every day in the lifts, now herded into buses bound for shelters.

Even after the bomb’s discovery, the city’s momentum proved difficult to arrest. Before the Explosive Ordnance Disposal (EOD) officers prepared to cut into its casing, the MTR kept running below. Beneath the suspended terror of 450 kilos of explosives, thousands of commuters were whooshing home for dinner, separated from history by a few metres of soil and concrete.

Amsterdam, 2025

In the end, the EOD officers successfully dismantled the bomb. The city metabolised the event, burying the memory just as the mud had buried the bomb for all those years.

Today, construction at the site continues. The percussive thud of piling turns the neighbourhood into a giant speaker cabinet, shaking our potted plants and my espresso in its tiny cup. Up above, black kites ride thermal waves between the high-rises and the wooded hillsides of Mount Parker. They drift over the slopes that drape down to meet the pavement, observing. I watch them circle, scanning what is below, just like the boys from their bridge above the canal.

But as the piling drives deeper, I wonder what else is waiting down there, holding its breath.

How to cite: Sullivan, Chris. “Disarming a Ghost.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal. 2 Feb. 2026, chajournal.com/2026/02/02/disarming-a-ghost.

Chris Sullivan is a photographer based in Hong Kong, where he has lived and worked for over a decade. His practice examines compression, mediation, and the limits of seeing. Working primarily in black-and-white photography, he explores whether photographs can do more than document, and whether they might also think. [All contributions by Chris Sullivan.]