Editor’s note: Julia Merican reads Lu Lei’s practice through meals, menus, embroidery, and exhibitions, attending to how intimacy operates as both method and politics. From private dinners with strangers to layered textile works, Lu uses food and language to negotiate migration, censorship, artistic complicity, and diasporic unease. The essay foregrounds slowness, listening, and ambivalence, showing how ordinary gestures become sites of dissent. Intimacy becomes a disciplined, ethically charged way of staying with contradiction.

[ESSAY] “A Seat at the Table: Lu Lei and the Politics of Intimacy” by Julia Merican

This is Illegal in Singapore (Diam Leh) (2023 -)

Private performance, approximately 1h – 4h

On a small kitchen table, just large enough to seat four, a table has been laid for two strangers. Fragrant steam rises from a bowl placed between them, its warm contours primed for eavesdropping. There are no labels, no programme, no instructions. The pair do not know each other and have little idea of where the evening’s conversation will lead. All they share, for the time being, is a home-cooked meal and the promise of each other’s attention.

I am intrigued by the quietness of this premise, intimate yet already laden with political implication.

This Is Illegal in Singapore (Diam Leh) is an ongoing performance by Lu Lei, an artist whose practice moves fluidly between food and text, performance and memory, the body politic and the body personal. Since 2023, she has hosted over thirty private meals with anonymous participants in whichever London flat she happens to be calling home.

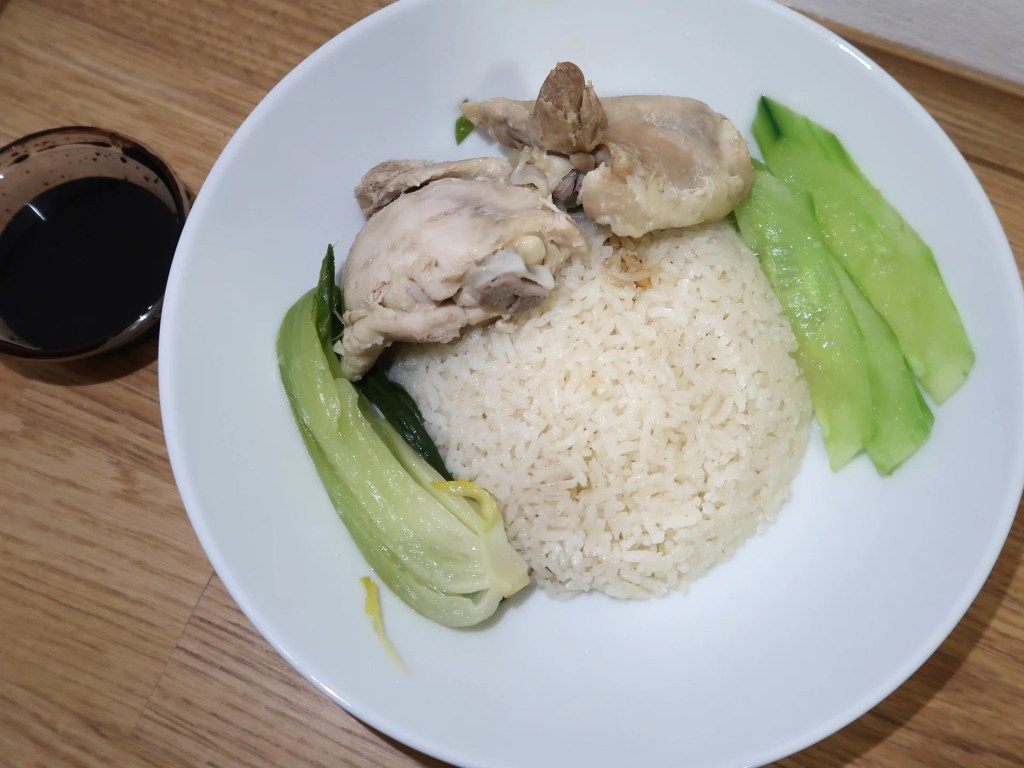

Over dishes of mee goreng or Hainanese chicken rice, beef rendang or bak kut teh, all cooked to suit each participant’s dietary needs, Lu and her guest take this shared act of breaking bread as a point of conversational departure. They might speak about family, an abstract feeling they are trying to name, or a particular worry occupying their thoughts. She describes the work as an exercise in empathy, a way of inhabiting another person’s subjectivity. “I invite people into my home because I want it to be a safe space. Cooking for loved ones is a love language, and I wanted to bring that same sentiment to an encounter with strangers in a foreign country, something close to the act of making someone a cup of tea in the UK. It requires faith from both sides,” she adds, smiling. “They’re trusting me to feed them, and I’m trusting them not to rob me.”

Hainanese chicken rice, via

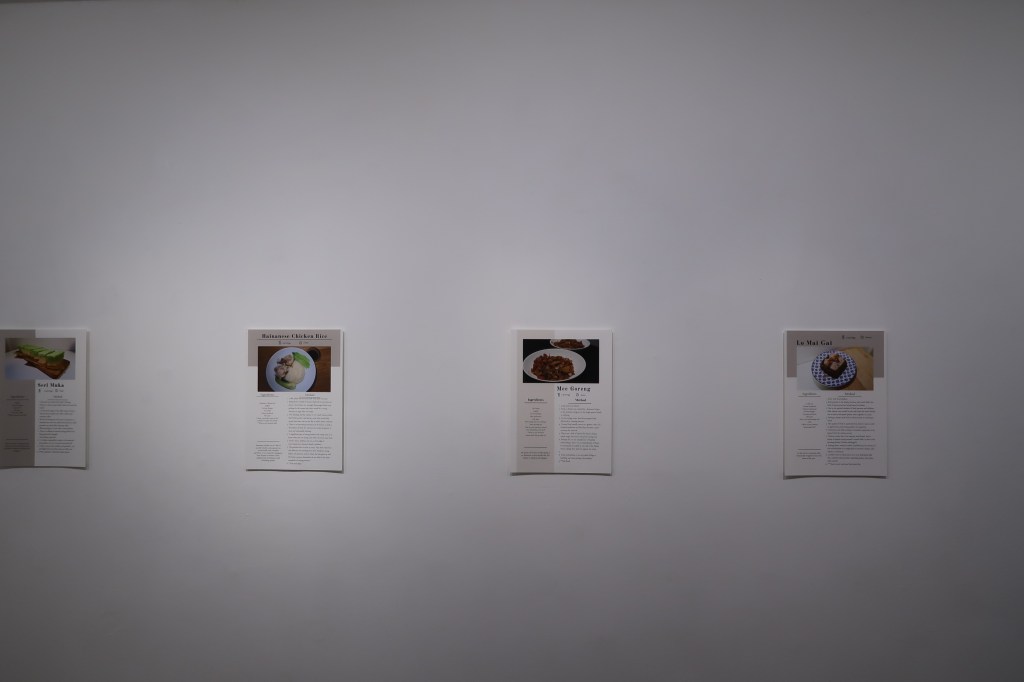

Menus from This is Illegal in Singapore (Diam Leh)

}

For Lu, the work is not about extraction, but mutual transformation.

Morsels of these discussions are preserved as menus, part of the artist’s expanding archive, which treats recipes as relics and food eaten together as a tool for emotional translation. For Lu, the work is not about extraction, but mutual transformation. Leafing through these recipes, I am struck by their vulnerability, by the way she has transfigured public objects of information into what feel like private documents, a well-thumbed letter or someone’s journal. Typical instructions, such as “serve with fried shallots”, are interspersed with tender and sometimes unsettling insights that linger in the mind long after, from “Both parents are busy with work daily but prioritise being home for dinner” to “The night before she ran away from home unannounced, she left a bowl of piping hot soya noodles on the table”.

This is Illegal in Singapore (Diam Leh) at Future Arts Festival, 2025

Gengdan Institution of Beijing Design Institute of Technology (BIT)

The project began as a more nuanced, less overt response to the politics of her home country. Born in China and raised in Singapore as a second-generation immigrant, Lu describes her complicated relationship with the place that has shaped her, one laced with unease. “I love Singapore,” she says, “and part of loving it means I’m going to be critical about its issues, its censorship, its death penalty, the privilege of who gets to speak and who doesn’t.” The title of This Is Illegal in Singapore (Diam Leh) enacts this tension, the way everyday acts, gathering, eating, conversing, can become quietly subversive under systems of control. In Singaporean slang, “diam leh” means to keep quiet or shut up, a nod to the opposition that she and many others have faced for speaking candidly about the nation’s politics. “I wanted the project to include more voices than just my own. Politics affects everyone.”

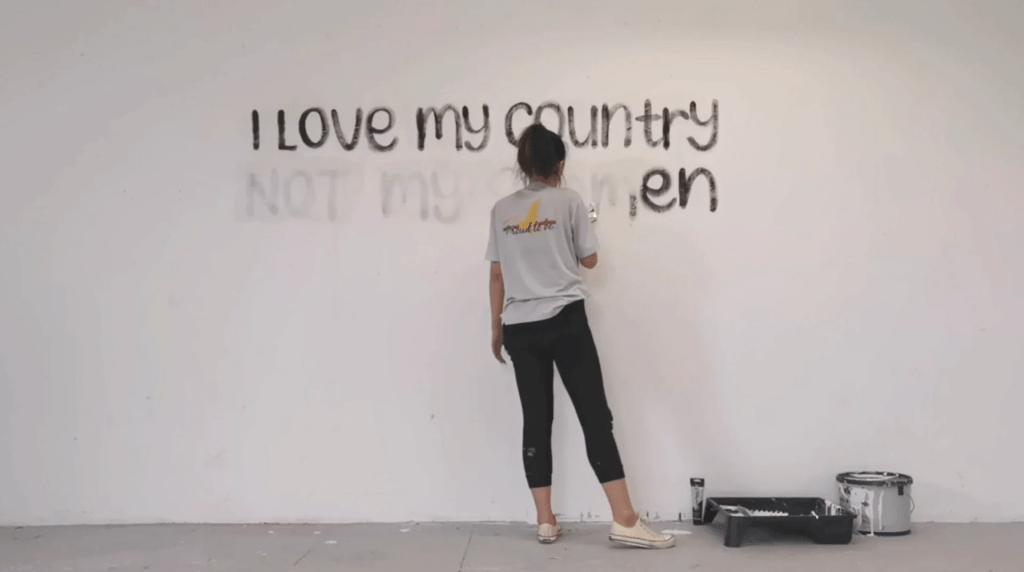

What interests me about Lu’s work is not protest or spectacle, but how dissent manifests through ordinary gestures. It is a strategy that feels both pragmatic and quietly radical, an ambivalence that extends to her own position as an artist. Lu is wary of the idea that art exists outside the realm of power. “If you show work in a gallery, you’re already inside a system,” she says. “And of course there is value in standing up from outside as well. Right now, I’m interested in what it means to work from within that contradiction.” Her practice occupies an uneasy middle ground, performing critique while still participating, testing which modes of dissent might slip through the cracks and break real ground. I read this not as indecision, but as a refusal to resolve discomfort, political or otherwise. Rather than settling contradictions for her audience, she stays with them, almost as if to test their endurance.

}

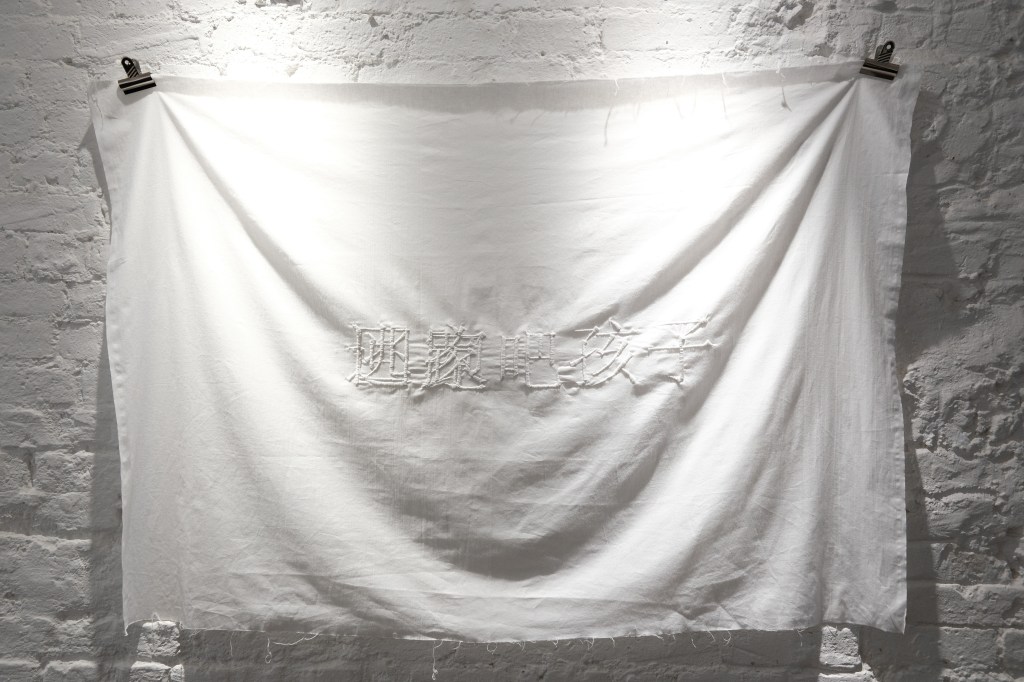

Wordplay is one of her favoured tools. In Zài Jiàn (再见), a text-based embroidered work, she plays with the duality of a Mandarin phrase that means both “goodbye” and “see you again”. “I love that it holds both departure and return in the same breath,” she says. “It’s a tension I’m familiar with.” I recognise in these words a broader logic that shimmers through her practice, namely that language is a site where instability is not a flaw, but an integral part of the architecture. For Lu, words, like people, flicker with layers of complexity.

再 (Zài) 见 (Jiàn) (2025)

Hand embroidery by Lu Lei on a weave by Xuan Yeo 9

5cm x 350 cm

Her first solo exhibition, “Discomfort Food”, shown at London’s Fitzrovia Gallery in 2024, embodied these ideas viscerally. Across performance, installation, and video works, Lu used food to surface histories of migration, nationalism, and repression. Some pieces were explicitly political, shaped by the resistance she has personally faced for speaking out about Singaporean politics. Others were quietly autobiographical, tugging at childhood memories in which certain flavours tasted both loving and constrained.

In a more recent 2025 exhibition at the 67 York Street Gallery, “Be the Crossroads”, the focus shifted from confrontation to reckoning. Inspired by the words of the Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish, the show lingered in the space between leaving and arriving, asking what it means to be perpetually divided between two states. One of its central works, Runaway Child, Come Home Child, which the artist sometimes stylises as ______, Child, takes the form of a layered embroidered text, Chinese words stitched over one another in different colours so that no single phrase fully dominates. Gazing at this work, my eye is unable to settle on any one element; the stitching enacts the restlessness it describes. “I was trying to express a conflict,” Lu reflects, “between wanting to escape a place and an equally strong desire to go back.”

_______, Child (2025)

Hand embroidery

135cm x 100 cm

These subtly overlapping threads weave a portrait that is both visual and emotional. They record how identity is never singular, or perhaps ever fully settled, in any sense of the word’s turbulent status. Just as Zài Jiàn holds farewell and reunion within the same characters, this work renders contradiction and irresolution visible.

Throughout Lu Lei’s practice, the body remains central, as site rather than spectacle. Whether she is serving a meal, embroidering cloth, or speaking with a stranger, her preferred medium is always art itself, understood as a conduit and vessel for exchange. Trained at Goldsmiths and the Royal College of Art after a rigid education in Singapore, she initially found the British art system disorienting, but also capacious. It offered her the space and distance to question inherited scripts.

To sit at her table is to step into a small, makeshift commons.

What emerges most strongly for me from her work is not only a manifesto, but a method, one that values slowness, listening, and the tender ethics of encounter. To sit at her table is to step into a small, makeshift commons, a place where the personal, the gastronomical, and the creative are always inherently political. In a climate that rewards fixed identities and clear allegiances, Lu offers something more precariously human, the courage to embrace contradiction, to say goodbye and see you again in the same gesture.

I Love My Country (2022)

Performance (approximately 15min)

How to cite: Merican, Julia. “A Seat at the Table: Lu Lei and the Politics of Intimacy.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 25 Jan. 2026. chajournal.com/2026/01/25/lu-lei.

Julia Merican is a writer living between Kuala Lumpur and London. In 2026, she will publish her first two books with Antigone Editions and MA BIBLIOTHÈQUE. She writes an occasional newsletter, Glimmers and Inklings.