Editor’s note: John E. Barrios examines Norberto Roldan’s Viva España, Long Live America, staged from 25 November to 31 December 2022 in Museo Iloilo and Kri8 Art Space, as a meditation on colonial afterlives. He traces how Catholic relics, American icons, literature, and vernacular objects are set in tense dialogue to expose postcolonial ambivalence.

[ESSAY] “Postcolonial Ambivalence in Norberto Roldan’s Viva España, Long Live America” by John E. Barrios

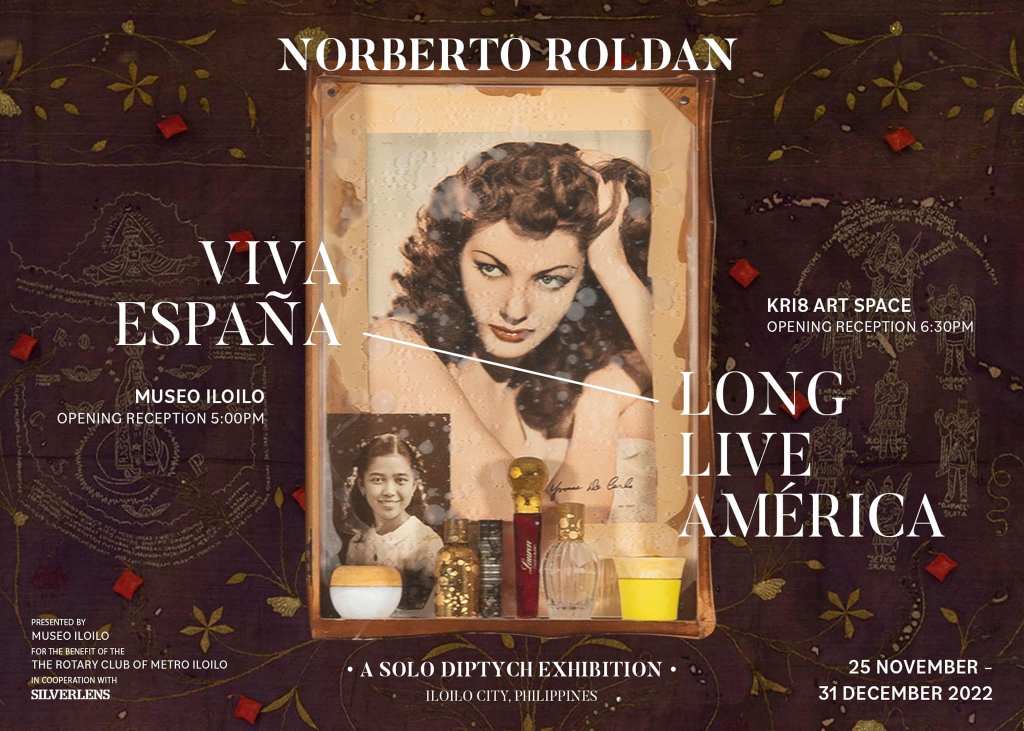

NORBERTO ROLDAN

VIVA ESPAÑA / LONG LIVE AMÉRICA

A solo diptych exhibition

25 November 2022 to 31 December 2022

Museo Iloilo, Iloilo City

Kri8 Art Space, Jaro, Iloilo

Presented by Museo Iloilo for the benefit of

The Rotary Club of Metro Iloilo

in cooperation with Silverlens Galleries

Norberto Roldan’s exhibition Viva España, Long Live America, held at Museo Iloilo and Kri8 Art Space in Iloilo City from 25 November to 31 December 2022, interrogates spatial and temporal discourses of colonial inheritance. The exhibition deliberately “colonises”, to use Roldan’s own term, two culturally and historically charged sites in order to stage a postcolonial position that critically examines Spanish and American legacies in the Philippines.

Museo Iloilo houses around 300 santos (saints) and religious artefacts from the homes of prominent Ilonggo families, bearing witness to more than four centuries of Spanish colonial rule and the entrenchment of Roman Catholicism. Kri8 Art Space, by contrast, occupies part of an ancestral house associated with the American colonial period and the wealth of hacenderos, notably Don Modesto Ledesma, a former mayor of Iloilo City. These sites are not neutral exhibition spaces but are themselves material embodiments of colonial history. Roldan mobilises their symbolic weight to interrogate Catholicism and American cultural influence as intertwined systems of power and belief.

Across both venues, the exhibition presents works produced between 2001 and 2022, encompassing painting, installation, assemblage, and mixed media. Roldan brings into dialogue precolonial religious objects and Catholic paraphernalia; indigenous beliefs and modern American commodities; literary texts by F. Sionil José and Jack Kerouac alongside Filipino and Hollywood celebrities; and imagery drawn from fashion magazines and archival photographs. These juxtapositions articulate what Roldan describes as the Filipino “love-hate relationship” with former colonisers. Rather than celebrating hybridity in a postmodern sense, the exhibition foregrounds postcolonial ambivalence, a condition marked by attachment and resistance, gratitude and resentment.

}

Viva España

The most enduring legacy of Spanish colonisation is Roman Catholicism. Together with military force, religion enabled Spain’s successful domination of the archipelago. Despite transformations brought about by indigenous syncretism and modern influences, Catholicism continues to shape Filipino social life and moral imagination.

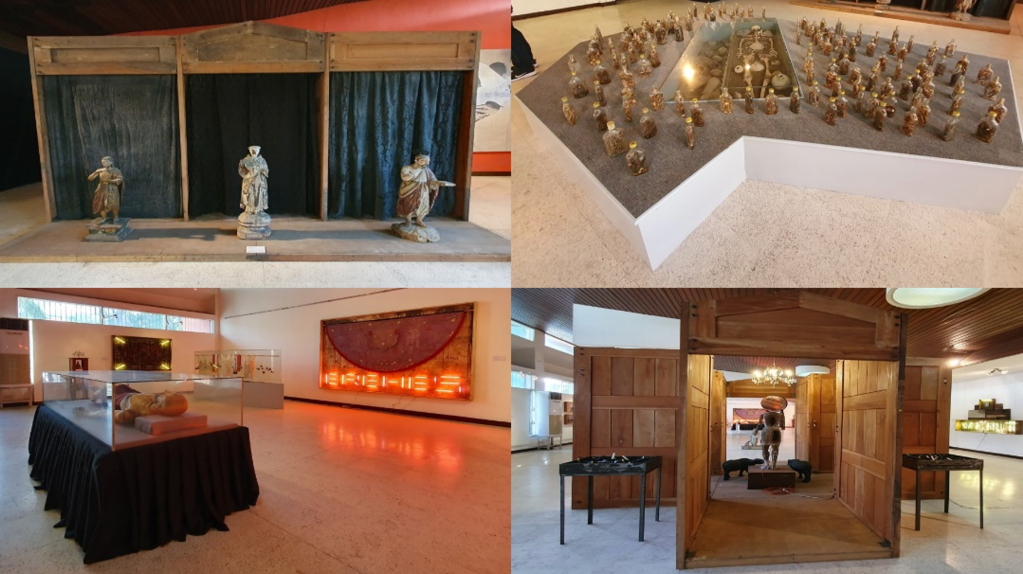

Roldan’s curatorial strategy at Museo Iloilo integrates the museum’s permanent collection into the exhibition rather than isolating it. The santos are positioned as “guards”, their backs turned towards contemporary artworks. Excavated skeletal remains and earthenware vessels are encircled by bottles of oil used as amulets (Garden of the Dead). A Santo Entierro is placed between illuminated text-based works reminiscent of urban signage (War on Faith and Erehes). Words drawn from prayers and amulets are inscribed on garments (Between Salvation and Damnation). Mannequins dressed in religious vestments and talismans (Rebel), or crowned with a globe and installed in candlelit sanctuaries (The Sacred and the Secrets in Our Lives), create charged encounters between Catholic iconography, indigenous belief systems, science, and everyday Filipino practices.

Fig. 1. The Dark Box, 2005–2022 (top left); Garden of the Dead, 2022 (top right); Erehes, 2017 (bottom left); and The Sacred and the Secrets in Our Lives, 2001–2016 (bottom right). (All images are by the author.)

Catholic hegemony is further amplified and exaggerated through monumental forms. A massive confessional and sanctuary frame towering images of Christ (Soy yo! [I Am He]), evoking patriarchal authority; the Virgin Mary (Mother of Perpetual Colony), suggesting relations of empire and colony, as well as master and slave; and a self-portrait of Roldan at sixteen, taken upon entering the seminary (Wear, Conquer), symbolising submission to the coloniser’s religion. Together, these works expose Catholicism as both a source of faith and a structure of discipline.

Fig. 2. Soy yo! [I Am He], 2002 (left); Mother of Perpetual Colony, 2002 (center);Wear, Conquer [Self-Portrait], 2002 (right).

Viva España thus functions simultaneously as celebration and critique. It acknowledges the depth of Catholic devotion in Filipino life while lamenting the vulnerabilities and forms of oppression embedded within it. The exhibition underscores the ongoing negotiation between Catholic doctrine, indigenous cosmologies, and the modern influence of American culture.

}

Long Live America

If Spain’s legacy lies in religion, America’s lies in education and cultural formation. As nationalist historian Renato Constantino argues, the education denied under Spanish rule was later deployed by the Americans as a tool to colonise Filipino minds. Through public schooling and substantial investment in education, American heroes, songs, and fantasies, including snow, Santa Claus, and consumer modernity, were readily internalised, allowing American culture to permeate Filipino society.

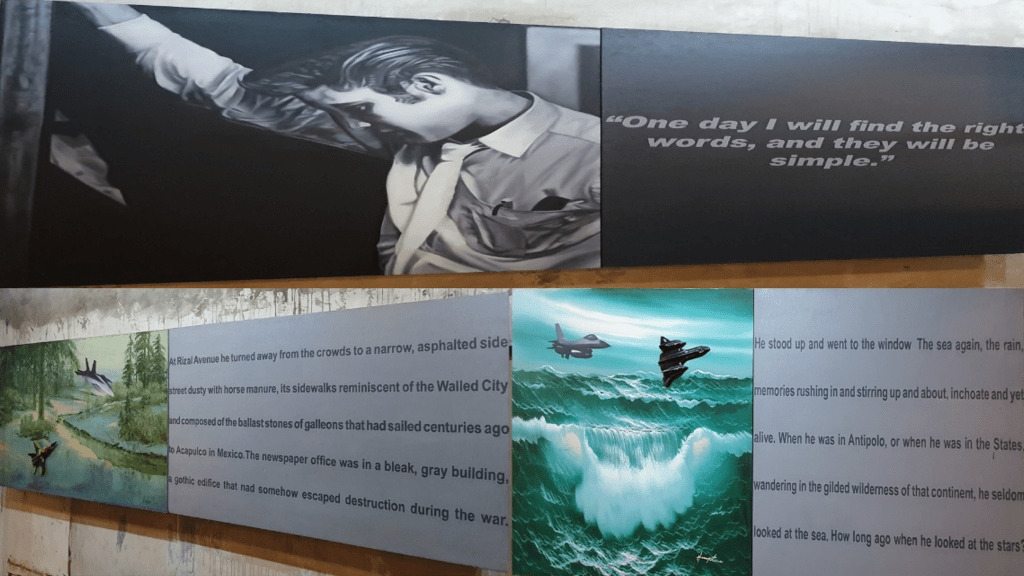

Roldan’s Pretenders No. 9 (Elvis Presley) encapsulates this process of cultural interpellation. The painting intertexts with F. Sionil José’s novel The Pretenders and a line from Jack Kerouac, “One day I will find the right words and they will be simple”, as well as Elvis Presley’s song “The Great Pretender”. These references converge on questions of identity, performance, and authenticity. Kerouac’s notion of simplicity, shaped by Buddhism, contrasts with Presley’s performative persona, mirroring the Filipino struggle to define selfhood under American influence.

Facing this painting are two found works signed “Hampton”, accompanied by quotations from The Pretenders that describe postwar Intramuros and the character Antonio “Tony” Samson. Tony is portrayed as “confused” between Antipolo and the “(United) States”, a spatial and psychological dislocation echoed in Fighter Jet Over Rizal Avenue and Fighter Jet Over Antipolo. The hovering jets suggest American military presence and surveillance, possibly evoking historical moments such as the deployment of United States aircraft during the EDSA Revolution. Tony’s eventual suicide in José’s novel underscores the tragic consequences of a freedom perpetually mediated by the American gaze.

Fig. 3. Pretenders No. 9 (Elvis Presley), 2014 (top); Fighter Jet Over Rizal Avenue, 2018 (bottom left); and Fighter Jet Over Antipolo, 2018 (bottom right).

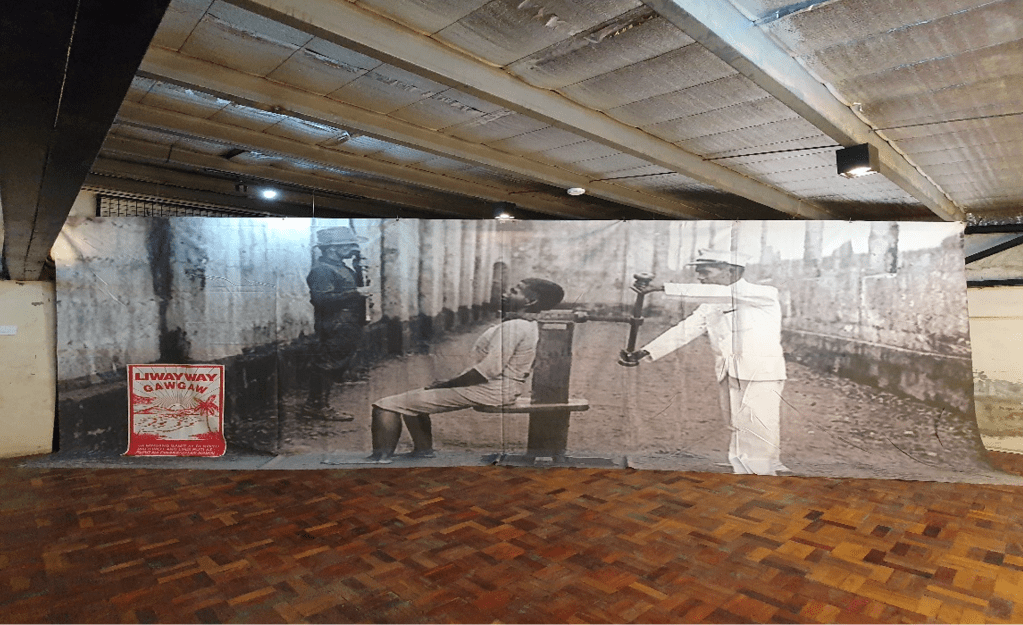

In the large-scale installation White Love, Love White, Roldan presents a Filipino executioner dressed in pristine white, garrotting a fellow Filipino. The stark whiteness of the executioner’s clothing is echoed by an advertisement for Liwayway Gawgaw, which proclaims, “You will never forget our pure-white cleanliness and total responsibility.” This visual rhetoric recalls President McKinley’s policy of “benevolent assimilation”, framed by the ideology of the “White Man’s Burden” and the notion of Filipinos as America’s “little brown brothers”, as articulated by Vicente Rafael. America appears as a paternal figure, while Filipinos are subjected to discipline and transformation under the promise of civilisation.

Fig. 4. White Love, Love White, 2002–2012.

Through intertextual staging, drawing on novels, historical accounts, popular icons, war imagery, and advertising, Roldan constructs interconnected identities of fictional characters, performers, Filipinos, and Americans. These identities are marked by postcolonial ambivalence: Filipinos garrotting fellow Filipinos, protagonists driven to suicide or murder, and American fighter jets occupying the same visual and temporal space. The exhibition articulates a hybrid Filipino identity that recognises colonial inheritance as both meaningful and futile, both gift and curse. In doing so, Viva España, Long Live America confronts the enduring sentiments of love and hatred that continue to shape Filipino memory and postcolonial consciousness.

Bibliography

▚ Constantino, Renato. “The Miseducation of the Pilipino.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 1, no. 1 (1970): 1–16.

▚ José, F. Sionil. The Pretenders. Manila: Solidaridad Publishing House, 1962.

▚ Kerouac, Jack. Some of the Dharma. New York: Viking, 1997.

▚ Rafael, Vicente L. White Love and Other Events in Filipino History. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2000.

Artworks Cited

▚ Roldan, Norberto. The Dark Box, 2005–2022. Viva España, Museo Iloilo, Iloilo City.

▚ ___. Garden of the Dead, 2022. Viva España, Museo Iloilo, Iloilo City.

▚ ___. Erehes, 2017. Viva España, Museo Iloilo, Iloilo City.

▚ ___. The Sacred and the Secrets in Our Lives, 2001–2016. Viva España, Museo Iloilo, Iloilo City.

▚ ___. Soy yo! [I Am He], 2002. Viva España, Museo Iloilo, Iloilo City.

▚ ___. Mother of Perpetual Colony, 2002. Viva España, Museo Iloilo, Iloilo City.

▚ ___.Wear, Conquer [Self-portrait], 2002. Viva España, Museo Iloilo, Iloilo City.

▚ ___. White Love, Love White, 2002–2012. Long Live America, Kri8 Art Space, Jaro, Iloilo City.

▚ ___. Pretenders No. 9 (Elvis Presley), 2014. Long Live America, Kri8 Art Space, Jaro, Iloilo City.

▚ ___. Fighter Jet Over Rizal Avenue, 2018. Long Live America, Kri8 Art Space, Jaro, Iloilo City.

▚ ___. Fighter Jet Over Antipolo, 2018. Long Live America, Kri8 Art Space, Jaro, Iloilo City.

How to cite: Barrios, John E. “Postcolonial Ambivalence in Norberto Roldan’s Viva España, Long Live America.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 21 Jan. 2026, chajournal.com/2026/01/21/Norberto-Roldan.

John E. Barrios is a Filipino literary critic, author, and academic recognised for his scholarship on regional Philippine literatures. He earned his PhD in Filipino-Panitikan (Philippine Literature) from the University of the Philippines Diliman and teaches in the College of Arts and Sciences at the University of the Philippines Visayas in Iloilo. His reviews and critical essays have appeared in various outlets, and he is the author of the book Kritikang Rehiyonal: Diskurso ng Lahi, Uri, at Kasarian sa mga Akda mula sa Rehiyon (Regional Criticism: Discourse on Race, Class, and Gender in Regional Literary Works), which examines literary production and criticism from the Philippine regions within broader cultural and theoretical contexts. He contributes to ongoing discussions on literature, culture, art, and regional identity.