Editor’s note: Laurehl Onyx B. Cabiles’s essay traces a Filipino upbringing in conflict-marked Cotabato and its unlikely resonance with Derry Girls. Through memories of militarisation, prejudice, and youthful fear, it shows how humour bridges distant histories, revealing comedy as a shared survival tool when ordinary lives unfold amid persistent violence worldwide today.

[ESSAY] “Why Does a Guy from Cotabato Province Relate to Derry Girls?” by Laurehl Onyx B. Cabiles

Carmen, Bohol, Philippines

Cotabato Province is located in the central part of Mindanao and lies on the eastern side of the SOCCSKSARGEN Region. Some people still call it North Cotabato. Its reputation, tarnished by numerous massacres and war crimes, has left a mark that persists to this day. As a result, neighbouring provinces and cities continue to regard it as a dangerous area.

Hearing the din of rotor blades when a helicopter flies over your roof, or seeing tanks accompanied by army trucks passing through your street, is not unusual for the residents. Each morning, men in uniform can be heard shouting their chants as they jog around. If not every day, then on most days, there is news of gun-shooting incidents.

Our hometown, Carmen, was on the safer side, but it was not always so. As far back as my memory reaches, there was a time when the town fiesta was approaching and, all of a sudden, there would be news of deaths caused by grenades. It would normally take a few days before everything returned to normal after those unfortunate events.

I did not meet many people from outside our town until I entered college. I took my bachelor’s degree at a respected state university in our province, the University of Southern Mindanao, located in Kabacan, a thirty-minute commute from our house.

The first day of my college journey remains vividly replayable in my mind. In that small chapter of my life, I realised that our humble province, where anyone could know anyone, could still surprise me. I remember when one of my classmates, who came from a rougher area, was asked to introduce himself in front of the class. He stood up and said, “I am Allen, and I am from the land of flying bullets.” The classroom erupted in laughter, as all of us had heard stories about the place he came from.

He stood up and said, “I am Allen, and I am from the land of flying bullets.”

Allen eventually became one of my dearest friends. Throughout the days we spent together, we shared dark and out-of-pocket jokes. Perhaps humour was the glue of our friendship, because even in serious moments we would find a way to blurt out something funny.

Derry Girls (2018-2022)

It was also in college that I stumbled upon Derry Girls. It is a television series created by Lisa McGee and first broadcast in 2018 on Channel 4, a British public-service television broadcaster known for commissioning programmes that foreground social realism, political commentary, and unconventional humour. The series is set in Derry, Northern Ireland, in the mid-1990s, during the final years of The Troubles, a period marked by sectarian conflict and political unrest. Rather than foregrounding violence or ideology, the narrative is carefully structured so that the political climate functions largely as background noise, shaping daily life without overwhelming it.

The story centres on a group of Catholic teenage girls, later joined by an English boy, as they navigate adolescence within a Catholic girls’ secondary school. Their concerns are strikingly ordinary, often bordering on the trivial, and include friendships, family tensions, romantic aspirations, academic anxieties, and social humiliation. Against a backdrop of army checkpoints, bomb scares, and peace negotiations, the series deliberately juxtaposes the weight of history with the self-absorption and impulsiveness of youth, allowing humour to arise from the contrast between the two.

Based on the premise alone, it might seem boring and bleak. However, if people were to give it a chance, they would see that each episode is written with humour. The scenes contain controlled chaos, dark humour, and delightful disasters.

Erin, one of the protagonists of the show, says in an episode, “Nobody good ever comes here because we keep killing each other.”

This line echoes something my friends would say. That is why I cannot help but resonate with the storyline and the nuances of the characters. Everything feels real and relatable to me, as though it mirrors my own experiences.

Series 2, Episode 1—”Friends Across The Barricade”

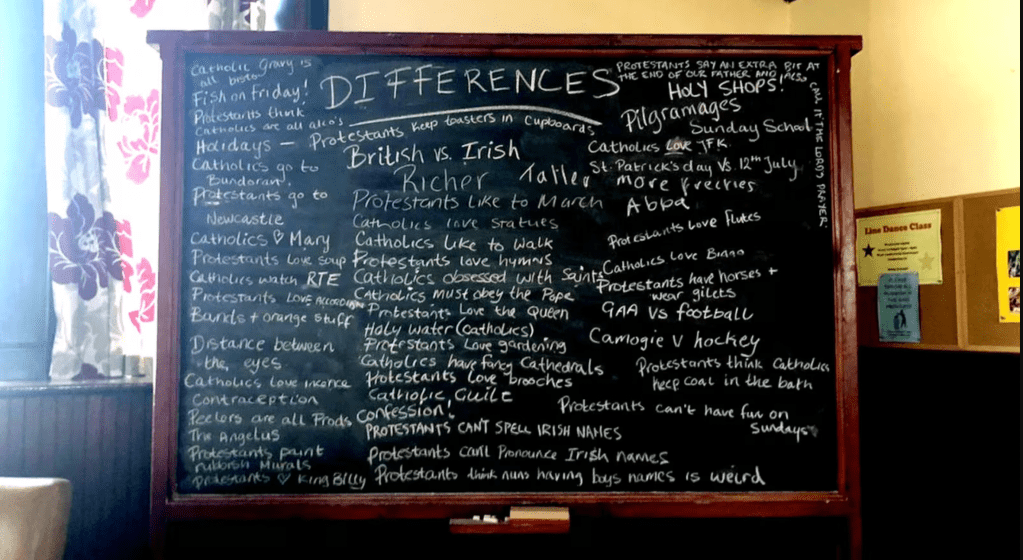

There is a particular episode in Derry Girls, “Friends Across the Barricade”, in which the protagonists join a retreat with Protestants from an all-boys school. The goal of the initiative is to foster a bond between Catholics and Protestants. However, from the first activity they share on their own, it becomes apparent that the experience will be riddled with misunderstandings. The protagonists’ preconceived notions about the Protestant boys become the very reasons the activities descend into chaos.

Whenever I watch that specific episode, I am reminded of a humorous experience born of my own ignorance and stereotypical attitude in the past. It happened during the early years of my college life.

At our university, there is a much-anticipated annual festival called Pasiklaban. It is a time when colleges across the campus compete against one another. There are many events during the celebration, and I was assigned to join a street-dancing competition. During the preparation period, I often had to go home late.

The transportation system in Kabacan at that time was unreliable. By eight in the evening, it was nearly impossible to find a multicab or bus bound for Carmen at the public terminal. If someone was favoured by the gods, they might find other passengers willing to rent a tricycle and split the fare.

As I was not particularly favoured, I would often ask the soldiers at the checkpoint to help me find a vehicle that could take me home. By then, I was accustomed to hitchhiking, and it no longer felt unfamiliar. The only thing that unsettled me during those nights was a running gag my friends had invented. Before we parted ways each evening, they would tease me about the horrors I might encounter on my journey, and I would respond with a joke of my own.

One night, while I was waiting for a free ride, the servicemen stopped a Suzuki Transformer multicab carrying men dressed entirely in white shirts, seated at the back. We spoke briefly about where they would drop me off before I joined them.

A few minutes into the ride, I confirmed, by asking about their destination, that the men were Maguindanoan, as the barangay they mentioned was predominantly inhabited by Moro people. At the time, I was a sheltered Christian boy. The negative stories I had heard since childhood accumulated in my mind, and at that exact moment, I allowed stereotypes to get the better of me. The dark, chilly road did not help. At the back of my mind, I was prepared to escape should anything go wrong. When one of them asked to stop the vehicle, I assumed they might kill me and throw me into the rice field beside the road. I stood up instantly, ready to jump. Before I could do so, however, the man who stepped out from the front seat asked whether I needed to urinate as well. To avoid an awkward situation, I pretended to do so. I was relieved that no one noticed my fear, and I thanked them sincerely when we reached my destination.

Later on, when I became a bed-spacer in an apartment near our school with my best friend Zulpikar, sharing a room with Maguindanoan people who eventually became my friends, my ignorance about their beliefs and culture was dispelled. They educated me about their struggles as a marginalised group.

As I look back on my younger years, I realise that my concerns were far less significant than the issues faced by my fellow countrymen. I have lost count of how many times I overlooked the struggles of those around me. I failed to perceive the injustices and inequalities hidden within the mundane.

Derry Girls occasionally reveals traces of The Troubles, but these moments are handled strategically, serving merely as inconveniences in the daily lives of teenagers. The programme foregrounds the characters’ amusing teenage escapades and pursuits. Humour emerges in unexpected scenarios.

I am aware that Derry Girls is set in a different period and that it is geographically distant from Cotabato Province. I also recognise that everything in the show is fictional. Yet I cannot help feeling that it all seems close and real.

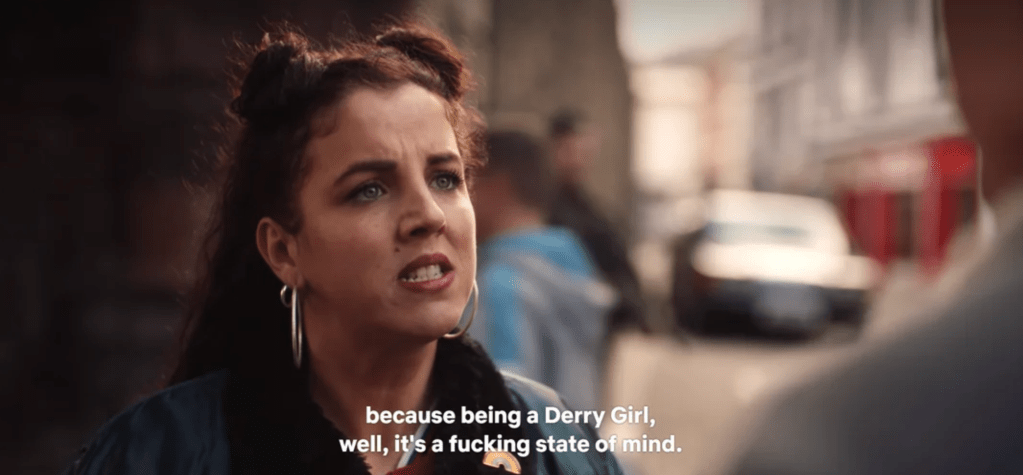

In one episode of Derry Girls, Michelle shouts at her cousin James, who is frequently bullied for being British, “Being a Derry Girl, well, it is a state of mind.”1

Even without setting foot in Derry, I find that I can still identify myself as a Derry Girl, because it is not simply about being from a particular place. It is about understanding, at heart, that when daily life is wedged between mundanity and bleakness, humour becomes a method of coping, an act of resistance. It is not a mask, but an oil that fuels people to continue pursuing their dreams and aspirations, even when violence still lingers.

- Season 2 finale, Episode 6, “The President.” ↩︎

How to cite: Caibles, Laurehl Onyx B. “Why Does a Guy from Cotabato Province Relate to Derry Girls?” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 19 Jan. 2026. chajournal.com/2026/01/19/cotabato.

Laurehl Onyx B. Cabiles is a writer from Cotabato Province. He holds a Bachelor of Arts degree in English Language. He has been a fellow in several writing workshops in Mindanao. His work has appeared inBangsamoro Literary Review, Ultramarine Literary Review, SunStar Davao, and Dagmay. [All contributions by Laurehl Onyx B. Cabiles.]