Editor’s note: Anna Nguyen’s essay critiques the literary marketplace’s fixation on identity, arguing that it rewards legible, consumable narratives while punishing rigorous resistance. Drawing on Glissant, Jordan, and Davis, she challenges flattened intersectionality, positionality statements, and the colonial gaze masquerading as radicality. Through reflections on rejection, family history, pedagogy, and uneasy solidarities, Nguyen seeks a politics of relation that honours opacity, resists nationalist roots, and foregrounds ethical connection over self-branding within contemporary writing cultures and academic institutions alike today and beyond.

[ESSAY] “I Write An Attempt Away From Identity Reductionism” by Anna Nguyen

I am trying to make a name for myself as a rigorous poet and prose writer. Accordingly, I scroll through opportunities to publish and find myself fascinated by thematic calls on this thing we call identity. The abstracts for these calls are strikingly similar in their vagueness and clichés. Editors seek submissions that ask writers to consider what identity means, how their identity is fractured, how they might reclaim identity in a fractured world, and how identity is tied to belonging or unbelonging.

The list of questions could continue indefinitely, producing endless variations of the same cumbersome enquiry.

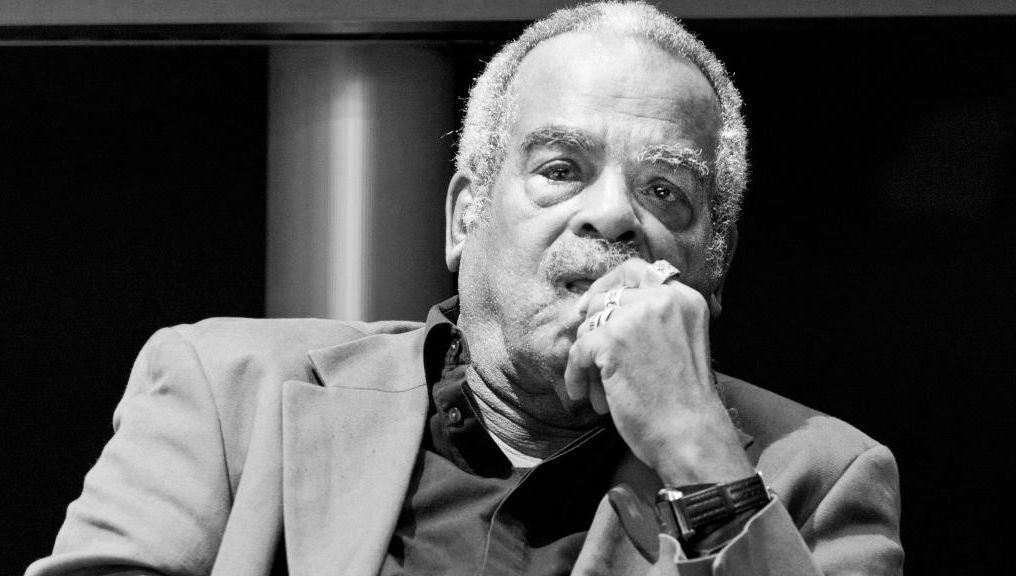

Édouard Glissant, 1928-2011

I attempt to write about identity, or, more precisely, to critique popular understandings of identity by interrogating what Édouard Glissant meant when he wrote that the “search for identity is tragic” (p. 17). Indeed, many writers and poets who centre identity do so in a tragic register, akin to what bell hooks has described as “eating the other.” Where hooks is specifically describing the ways in which the dominant group consumes and commodifies the minoritised group through mass media (p. 308), I want to draw attention to how we, the minoritised, self-consume our own Otherness in order to differentiate ourselves from the majority. They, or we, do so by shuffling through identities, as if identity alone could explain why and how we operate on different planes of the same world.

These narratives of identity become even more tragic. Despite their, or our, best efforts in producing formulaic self-evaluations of identity, such works are consumed by the dominant group, who then view them, or us, as people to learn from, to better themselves, to unlearn systemic racism. It is as if they cannot read any other story about us. They see these writers only as educators, never as full humans. Some of these writers, in turn, embrace yet another identity, that of the educator.

)

I am trying to write outside these reductive narratives. My attempts, however, are not readily embraced. I submit my work to seemingly radical feminist literary magazines and to Asian diasporic journals. My pieces are routinely rejected. I suspect this is because I do not enlist themes that are legible to them. This stance contradicts their, or our, professed embrace of another concept, illegibility, which has been mobilised as a reactive craft tool, a means of writing outside the dominant narrative and dominant storyline, and away from colonial time.

I regard this as a misuse and a misunderstanding of Glissant’s argument against legibility. The phrasing of “rights” carries a legal undertone, but Glissant’s concern is a call for the right to opacity beyond the Western colonial gaze (p. 189). People can exist, and their experiences need not be reduced or categorised. Yet we should be cautious with Glissant’s generosity. He may argue that everyone has the right to opacity, and that anyone can cite Glissant, but not everyone lives in opposition to the colonial gaze.

Some of their, or our, writing exists through the reproduction of that very gaze.

Other terms synonymous with illegibility include promiscuous and radical.

I find no trace of these essays and poems that claim illegibility, promiscuity, or radicality when they ultimately serve the colonial gaze.

And yet I continue to write, as an attempt.

)

I am always trying to write my parents’ stories, many of which are more compelling than my own. While I have strategically drawn on some of their experiences in my writing, in stories that are not quite my stories, I do not wish to be their stenographer. I do not want their lives to be consumed or rendered into caricatures of Asian refugees and immigrants through careless analysis and misinterpretation.

Yet I am not rewarded for restraint. My stories and poems, which are fundamentally critical in nature, do not appear to fit within conventional understandings of diaspora, or of identity.

My parents and I both belong to a diaspora. Perhaps we belong to multiple diasporas. Yet they cannot read my words. We do not share the same languages.

My father has passed away. His stories continue to haunt me, and it is difficult to write about him without my chest constricting in anguish and pain. I cannot share those stories because they would ultimately become stories about me, even as I attempt to write about my father without appropriating a life marked by suffering.

My mother and I do not read in the same language. So who can consume my stories, if not the very person I am writing about?

My older sister and older brother died before I was born. We are relatives, but our relationships are ghostly. If I were to write about them, how could I do so without invoking the trope of intergenerational trauma?

These are the kinds of questions I ask when I write about identity.

And so many of my rejected drafts and manuscripts remain stacked in their folders, their current homes.

)

June Jordan, 1936-2002

I am writing to ask those who claim to write about identity what they truly mean by identity. They, or we, must also be writing about race, and so the question becomes how one writes about race without eulogising eugenics and nationalism.

I reread June Jordan’s “Report from the Bahamas,” an essay that addresses consciousness of race, class, and gender identity (p. 7). Many would categorise these three taxonomies as intersectionality. This may be an accurate interpretation, particularly when one relies on the citation of another’s framework, but Jordan herself does not use the term intersectionality.

I am writing to interrogate how intersectionality has become flattened. White writers are eager to invoke intersectionality. Yet they omit class, ignore race, and define gender as fluid without acknowledging that these categories are mutually imbricated. They wish to claim that they are ever evolving and ever changing, that their identities are not stagnant.

I am writing to invoke the profoundly salient arguments Angela Davis advances in Women, Race & Class, in which she documents how historically celebrated movements, such as women’s suffrage, abolitionism, and the women’s liberation movement, were created for and by white middle-class women who deliberately excluded Black women, other women of colour, and working-class communities.

I am not writing to argue that fluidity is absent from identity. Glissant’s figure of the errant rejects fixed notions of identity in order to critique the idea of a “totalitarian root” that “threatens to kill everything around it” (p. 12). This root grows and thrives in the West, “where this movement becomes fixed and nations declare themselves in preparation for their repercussions in the world” (p. 14). Such a root describes an identity that claims land and others, an empire built upon roots. Fluidity, in a more rigorous sense, can instead be found in the errant figure who possesses “rhizomatic roots,” which rely on relationality, forming “a network spreading either in the ground or in the air, with no predatory rootstock taking over permanently” (p. 11).

This errant, rhizomatic figure may embody a form of rootedness, but it must remain open and perpetually mobile in relation to land and to others.

I am writing to remind them, or us, that while we may appreciate the poetics of Glissant’s prose, we cannot forget his political analysis of identity. Identities are fluid because we must reject coloniality in order to sustain our pursuit of freedom.

Errantry and the rhizomatic are not compatible with nationalist expansion. They do not describe world travellers seeking to unlearn through the consumption of others’ cultures or through voyages to foreign lands. Nor do they justify self-congratulation for expatriate status, which often signifies little more than the privilege of a white subject who can leave one community secure in the knowledge that another white community awaits. Rather, they insist that identity is rooted in political struggle, political desire, and political demand.

I write to remind us that we should cease praising European countries, particularly those in Scandinavia. Each day I encounter Americans lamenting the current state of their country and expressing a desire to leave.

I write to remind us that these same countries consistently reappear in annual rankings of the Best Places to Live. They are good places to live for white people because they are inhabited by white ethnonationalists.

I write this sentence and recall a time when I wished to visit Sweden while living in Germany, before I grew weary of Europe’s unearned reputation for being more progressive and more accepting than the United States. I did not wish to move from one white supremacist state to another.

I write to remind us that we ought to abolish binaries, including “foreigner” and “citizen,” because these distinctions enable self-identification at the expense of others, without regard for relationality. Glissant observes, “The duality of self-perception (one is citizen or foreigner) has repercussions on one’s idea of the Other (one is visitor or visited; one goes or stays; one conquers or is conquered)” (p. 17).

I write to remind us that these binaries and assumed fixed identities are, in fact, power asymmetries that we continue to accept, even as some claim to abolish or banish them.

)

I am writing to ask them, or us, not to resort to the nefarious use of positionality statements, which have become a means of reinforcing identity reductionism, functioning as a swift apology before a return to analytical greed.

I am writing to cite Gani and Khan’s compelling argument that positionality statements operate as a function of coloniality, given that positionality itself has its origins in colonial epistemes (p. 2). This genealogy appears to be unknown to those who eagerly open their work with a positionality statement. Gani and Khan seek to problematise this practice that they, or we, hold so dearly. Their argument should not be misread as a return to objectivity, but rather as a demonstration that even our subjectivities have limits (p. 2).

I am writing because I briefly close my eyes in anger when I hear someone begin a presentation with a positionality statement. They announce that they are not explicitly the Other, yet express a desire to belong to the community, only to return to extractive work that is not emancipatory but instead reproduces hierarchical and racialised power dynamics. These dynamics are often presumed to be disguised by a performance of privilege awareness. Positionality statements do not absolve inequity within a room.

I am writing because I want to confess that I am persistently attentive to who is writing what, drawing on whose research, and how careful scholarship can be reduced into harmful knowledge production. I write this sentence in memory of an unsurprising discovery of yet another white Canadian academic publishing a new book on Indigenous communities. My curiosity led me to research this individual, who identifies as a settler researcher, a designation I find perplexing. Even more troubling is the fact that this white Canadian academic requires prospective Indigenous students to prove their Indigeneity to someone who self-identifies as a settler researcher.

I am writing to suggest that they, or we, read Gani and Khan’s critical work with care. Although it is an academic intervention situated specifically within the field of international relations, we ought to value rigorous scholarship that underpins many personal essays. We should also attend to international relations if we wish to become errant, rhizomatic figures, because Glissant is, fundamentally, an internationalist. International relations require looking beyond one’s spatial identity.

)

I want to write a version of Jordan’s “Report from the Bahamas,” which at first reads like a travel essay but is, in fact, an unfolding consciousness of race, gender, and class during a trip to a formerly British-colonised country. It also reads as a flawless self-evaluation of Jordan’s own fluid identities, as a Black woman and as a tourist whose position is at odds with that of the Black hotel employees at the Sheraton British Colonial. Their interactions are fixed and transactional, “designed to set us against each other” (p. 8).

I am writing because I know it is controversial and untoward to write about students when one is an instructor. Yet this remains one of the most consistent spaces in which I experience race, gender, and class consciousness as a precarious worker. This is not, however, about the instructor student dynamic itself, but about what it means to teach today. In one of Jordan’s digressions, which does not take place in the Bahamas, she recalls praising a white graduate student’s final paper. The student responds by telling Jordan that she is lucky, prompting Jordan to ask for clarification. The student praises Jordan for living a life of purpose and cause, listing “Poverty. Political violence. Discrimination in general” (p. 10). Jordan asks whether the student herself has a cause, to which the student replies that her non cause is “I’m just a middle aged woman: a housewife and a mother. I’m a nobody” (p. 10). The pedagogical lesson is not merely that identities are racialised, but that Jordan is interrogating what history narrates and archives.

This apparent tangent is not a tangent at all, as it returns the reader to Jordan’s trip to the Bahamas, which begins with her reading a message from the Ministry of Tourism that offers a celebratory account of settler colonialism while strategically omitting violence. There is also an omission of significant figures in both Black and white histories, figures who “exclude from their central consideration those people who neither killed nor conquered anyone as the means to new identity, those people who took care of everyone of the people who wanted to become a ‘person’” (p. 11). Jordan is speaking of women within these exclusionary narratives.

Yes, I write frequently about whiteness fatigue, but I am writing here because anger is often easier to sustain than reflection. Rereading “Report from the Bahamas” forces me to consider Jordan’s insistence that “the ultimate connection cannot be the enemy” and that “the ultimate connection must be the need that we find between us. It is not only who you are, in other words, but what we can do for each other that will determine the connection” (p. 14). Jordan locates this connection upon her return to her teaching position in the United States, where she teaches contemporary women’s poetry. A young Black woman from South Africa asks Jordan for help because her alcoholic husband is assaulting her. Jordan desperately contacts everyone on campus, seeking assistance for the battered student, only to discover that “there were no institutional resources designed to meet her enormous, multifaceted, and ordinary woman’s need” (p. 15). It is another student, a white Irish woman active in campus IRA activities, who helps Jordan support the young Black student. Jordan follows the two women as they walk to the car, stunned, while recalling memories of being terrorised by Irish children who once hurled a racist epithet at her.

I recount the ending of “Report from the Bahamas” because I cannot help but remember a story that is not mine, though I am implicated in it. I had invited a close comrade to Germany to present at a workshop I had organised. She is a Black feminist scholar from Kenya studying in Ontario. She missed her flight in Toronto after her train was delayed. She called me in tears, panicked because an airline agent, a young Asian woman, had been hostile and refused to assist her. Another agent, a young white woman, quietly intervened and helped her secure another flight.

It had been a long day of travel for my comrade. There are aspects of the trip she does not remember. Yet we both remember this moment at the Toronto airport, though for different reasons.

I am not writing about Jordan and this vignette to suggest that there are good white people in the world. Nor am I writing to absolve whiteness. I am writing to interrogate what we call community and our tendency to believe that our skinfolk will rescue every crumbling institution. I am writing to argue that criticising whiteness is easy precisely because it so rarely disappoints us in its most blatant expressions. My provocation is that, when institutional loyalty is at stake, our skinfolk are often those who disappoint us most. They, or we, hunger for power to such an extent that an institutional identity is forged, extracted from experience, trauma, struggles for acceptance, and a desire to be seen, at the cost of relinquishing relational ties in order to exist at the periphery of the majority.

And so I am writing to suggest that there are lessons to be drawn from the recognition that skinfolk does not mean kinfolk. We might instead attend to moments of connection like those Jordan describes in “Report from the Bahamas,” moments that rarely find their way into our writing, which so often excludes ordinary acts of solidarity and genuine care.

And so I continue to write, attempting to capture these complexities of identity without reproducing identity reductionism.

Bibliography

▚ Glissant, Édouard. Poetics of Relation. 1990. Translated by Betsy Wing. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1997.

▚ hooks, bell. “Eating the Other: Desire and Resistance.” In Media and Cultural Studies: KeyWorks, 2nd ed., edited by Meenakshi Gigi Durham and Douglas M. Kellner, 308–18. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2012.

▚ Gani, Jasmine K., and Rabea M. Khan. “Positionality Statements as a Function of Coloniality: Interrogating Reflexive Methodologies.” International Studies Quarterly 68 (2024): 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1093/isq/sqae038.

▚ Jordan, June. “Report from the Bahamas, 1982.” Meridians 3, no. 2 (2003): 6–16. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40338566.

How to cite: Nguyen, Anna. “I Write An Attempt Away From Identity Reductionism.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 19 Jan. 2026, chajournal.com/2026/01/19/attempt.

Anna Nguyen left her PhD programme and reworked her dissertation into a work of creative non-fiction while studying for an MFA at Stonecoast, University of Southern Maine. Her work brings together literary analysis, science and technology studies, and social theory to examine institutions, language, expertise, citation practices, and food. She is currently undertaking a second MFA in poetry at New England College, where she also teaches first-year composition. She is the host of the podcast Critical Literary Consumption. [All contributions by Anna Nguyen.]