茶 FIRST IMPRESSIONS

茶 REVIEW OF BOOKS & FILMS

[REVIEW] “Off-Kilter Worlds and Authoritarian Futures in Ysabelle Cheung’s Patchwork Dolls” by Jennifer Eagleton

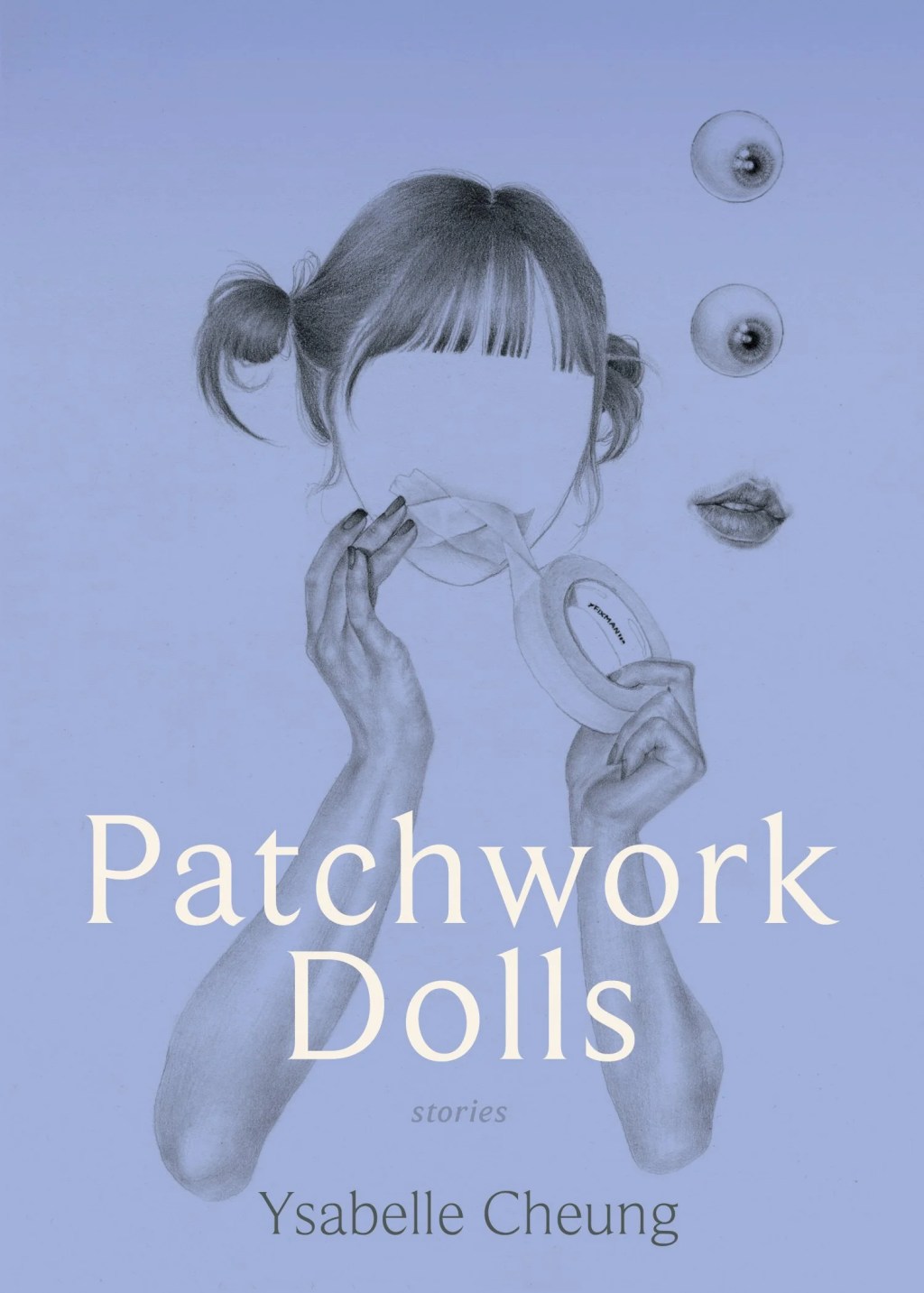

Ysabelle Cheung, Patchwork Dolls, Blair, 2026. 200 pgs.

Ysabelle Cheung’s stories are clearly connected to contemporary society, yet they are set in off-kilter, defamiliarised worlds. Drawing on an amalgamation of science fiction, myth, and magical realism, Cheung exposes the dangers that arise when memory, history, and identity disappear, as well as the difficulty of breaking free from social expectations and governmental dictates.

The collection opens with the Kafka-like story “Mycomorphosis”, a strange tale of a woman whose body becomes a breeding ground for various kinds of fungi. Her debilitating migraines are diagnosed as “extra fungus in your head”. Once diagnosed, she begins to see “brain fungus everywhere”, and as the fungi continue to grow, the narrative shifts into one of rebellion. Her condition becomes “something stickier; and rebellious”, as she grows increasingly defiant toward both societal norms and the expectations imposed by her peers.

“Please, Get Out and Dance” recalls Yoko Ogawa’s The Memory Police, echoing its surreal exploration of memory, trauma, and loss. In Ogawa’s novel, an unknown force causes the inhabitants of an island to forget objects and concepts collectively, along with their emotional attachments to them. In Cheung’s story, things also disappear. People are informed of the supposed benefits of this loss, yet they continue to hold funerals for what they can no longer possess. After the authorities implement “a central network system that tracked and classified everything”, a date is selected on which citizens are required to get out and dance. This date “was fortuitous”. According to the almanac, it was “a good day for change”, becoming an “enforced tradition” in which “nationalism veiled itself in culture”. In response, a group of rebels flee the vanishing city to establish a new home beneath the ocean, defying the government’s mandate. The story inevitably recalls Hong Kong’s political situation. Readers may recognise parallels between the “central network system” and contemporary security legislation, as well as efforts to reshape the city’s historical narrative and redefine “patriotism” as a core civic value.

In “The Reader”, the sudden disappearance of books signals a broader meditation on memory loss and the impossibility of writing without remembrance, as society suffers from a form of collective amnesia. The story is arranged in an unusual manner, with the narrator offering instructions on how to navigate its interconnecting threads through the use of italics and blank spaces. This structure highlights the difficulty of disentangling deliberate obfuscation from genuine attempts to clarify historical narratives. The text also refers to an unnamed city in which protesters dressed in black and raised “five fingers” in demonstration. Although the city is clearly Hong Kong, the phenomenon of disappearing books is far from unique to it. “To My Great-Granddaughter, Who Will Find This Letter When I Am Dead” likewise engages with time, memory, and remembrance, using food and journeys through the city to enable a future generation to recall events that have been erased through the loss of books, the spread of misinformation, and the repeated utterance of lies.

In “Patchwork Dolls”, the story that gives the collection its title, women known as “patchwork dolls” sell their faces to “affluent white women” seeking “an upgrade to newer, trendier (and ethnically ambiguous) faces”. The procedure, known as “transdermal patchworking”, is controversial because it reinforces “murky racial inequities”, with those selling their faces described as “primarily disadvantaged women of colour” who need the money. The narrator, who has experienced anti-Asian racism, remains deeply unsettled. As she observes, “On a white woman, my face was desired, ambiguous, a symbol of power and wealth. But for me it had been a curse, something I desperately needed to scrub out”.

In “Herbs”, the reader follows an elderly widow whose dead husband begins to reappear in the form of unsolicited clones. She is forced to confront her memories of him at different stages of life, from youthful naivety at 21, to emotional abuse at 45, to familiarity at 75. As reliving this history becomes intolerable, she takes decisive action to address the increasingly distressing situation.

In “Find Your Spirit”, a woman’s deceased twin sister returns to persuade her to download an application that tracks the unliving “as long as she remains close to the earthly plane”. This “ghost tracker”, however, gradually transforms the sister into a virtual presence that no longer resembles the person she once was. The story suggests that, as a twin, the protagonist may ultimately be searching for an understanding of herself rather than for her lost sibling.

In “Galatea”, set in China, a woman visits her date’s apartment and eventually leaves with his Companion Doll, which he insists is “not a sex toy…. more for companionship”, though it resembles “a generic female office worker”, much like the woman herself. The man explains that the dolls will ultimately collaborate with the government, outlining a vision in which they eliminate the need for migrant workers and caretakers by prioritising efficiency. The implication emerges that the woman herself may already function as a kind of Companion Doll.

Matched cohabitation forms the subject of “The In-Between”, in which a matchmaking company attempts to identify a “true couple” by ensuring long-term compatibility through extensive data collection. The process claims to be “being sensitive to expectations” by uncovering every detail about potential partners, leaving nothing to chance or risk in the pursuit of relational success. One character remarks that the entire data-gathering process is stressful and exhausting, asking, “If they liked each other, wasn’t that enough?”.

“Not in This Neighbourhood” is an anti-immigration story told from the perspective of an interplanetary migrant. “She had chosen America simply because she had been to no other place on Earth”, yet her name is reduced to “T” due to the difficulty of pronouncing its “sloping vowels”. Although mass migration is initially encouraged, “the narrative changed from a language of community to one of singularity, of hostility”. The story reflects a familiar contradiction: while migration by disadvantaged groups is often welcomed in the abstract, the practical demands of integration are frequently resisted.

Taken together, the stories in this collection explore the dangers of technology pushed to extremes, the rise of authoritarian tendencies, and acts of rebellion against social norms and imposed expectations. They forge a compelling link between the present and an uncannily altered potential future, defamiliarising contemporary reality while keeping it unmistakably recognisable. The suggestion remains that there is still time to alter that future.

How to cite: Eagleton, Jennifer. “Off-Kilter Worlds and Authoritarian Futures in Ysabelle Cheung’s Patchwork Dolls.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 18 Jan. 2026. chajournal.com/2026/01/18/dolls.

Jennifer Eagleton, a Hong Kong resident since October 1997, is a close observer of Hong Kong society and politics. Jennifer has written for Hong Kong Free Press, Mekong Review, and Education about Asia. She has published two books on Hong Kong political discourse: Discursive Change in Hong Kong(Rowman & Littlefield, 2022) and Hong Kong’s Second Return to China, A Critical Discourse Study of the National Security Law and its Aftermath(Palgrave Macmillan, 2025). Her poetry has appeared in Voice & Verse Poetry Magazine, People, Pandemic & ####### (Verve Poetry Press, 2020), and Making Space: A Collection of Writing and Art (Cart Noodles Press, 2023). [All contributions by Jennifer Eagleton.]