茶 FIRST IMPRESSIONS

茶 REVIEW OF BOOKS & FILMS

[ESSAY] “Filmic Silence and the Speaking Body in the Novel” by Thammika Songkaeo

Click HERE to read all entries

on Stamford Hospital.

Eva Trobisch (director), All Good, 2018. 93 min.

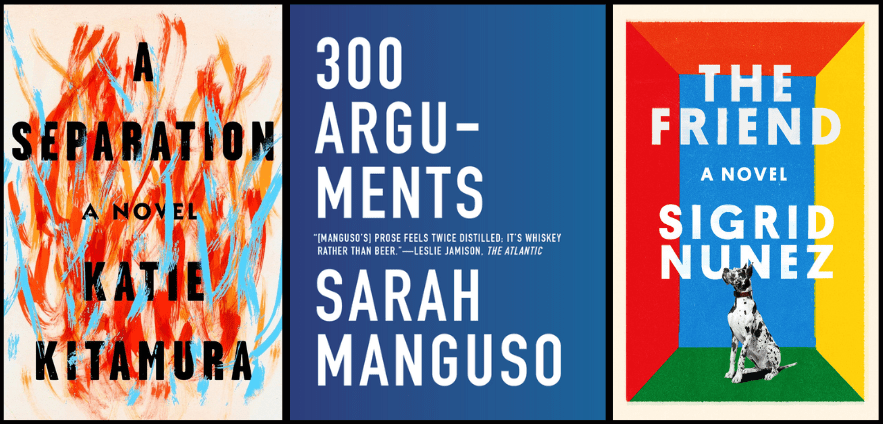

In 2020, the words of Stamford Hospital, then titled The Travelling of Sound, poured into a notebook while my computer screen played Eva Trobisch’s All Is Well (also titled All Good) on Netflix. Not all of my writing is inspired by film. Much of Stamford Hospital, now queried for film adaptation, owes its lineage to literature, including Katie Kitamura’s A Separation, Sarah Manguso’s 300 Arguments, and Sigrid Nunez’s The Friend, texts that privilege meditation over plot. Yet cinema became central to how I learned to pace, structure, and ultimately trust my scenes. Through watching film, I learned how to marry my interest in meditative writing with “an actual plot”, arriving at a style that feels true to my goals as a writer.

All Is Well became my most consistent cinematic companion over the four years it took me to complete the novel. The film taught me how to register emotional beats visually, how to stretch scenes without dialogue so that silence itself accrues meaning depending on where the camera, and thus the narrator, rests. Trobisch’s work offered a lesson I returned to repeatedly: narrative propulsion does not require constant action. It can emerge from attention, withholding, and the pressure between what is shown and what is left unsaid.

On the surface, All Is Well and Stamford Hospital are distinct. Trobisch’s film centres on Janne, a woman changed by rape, while my novel begins with a mother responding to her young daughter’s cough, a moment that leads her to hospitalise a barely ill child, using the hospital as temporary childcare so that she can attend to her own unmet needs. Where All Is Well proved invaluable was in helping me develop a visual and narrative vocabulary for trauma, not trauma as spectacle or confession, but trauma as something lived quietly in the body, with the central conflict becoming how one survives it in the face of ordinary life.

In a Guardian article titled “My streaming gem: why you should watch All Is Well”, Caspar Salmon observes that although the film concerns sexual assault, it “thumbs its nose at the register of darkness you might expect”. Darkness, so often treated as something to fear or sensationalise, had always been present in my writing. In early drafts of Stamford Hospital, however, that darkness often appeared as plotless meditation: phrases that sounded profound, fragments that felt cathartic to write, but that floated without narrative anchor. At the time, I believed, perhaps incorrectly, that I was capturing a kind of wisdom about life. I resisted, despite feedback from early readers, the pressure to create a more conventionally compelling story. Before encountering All Is Well, I worried that such narrative demands would betray the truth about trauma that meditation alone seemed able to hold.

Watching All Is Well changed my thinking. I saw how Trobisch generated emotional pull without relying on dramatic turns. Janne never names her attacker, never seeks revenge, never arrives at a moment of reckoning. So if she does none of the expected narrative acts, what does she do instead? The answer lies in the body. We watch Janne brush her teeth after the assault, wake and drink water, smile on the phone while agreeing to visit a friend. These gestures of normalcy are devastating precisely because they contradict what we assume trauma should look like. The film refuses articulation and forces the audience to experience meaning somatically, through tension rather than explanation, an approach Stamford Hospital would eventually adopt wholeheartedly, and one that ultimately resonated with readers.

Through my sustained engagement with All Is Well, I learned to trust more deeply the instinct I had been circling all along: silence. Silence is not merely the absence of speech; the body is always speaking. As a writer, I took this as permission, and as instruction, to let the body speak in Stamford Hospital. I became interested in how gesture, sensation, and physical response could carry narrative force where language receded. In this space, I found a middle ground between the pressure for plot voiced by early readers and my own intuition that psychology remains narratively potent even when plot is deliberately muted. Interior contradiction, I learned, can itself generate momentum.

That lesson shaped the novel’s central dissonance. Visually, Stamford Hospital moves towards reassurance: white rooms, professional competence, institutional order. Internally, the protagonist Tarisa moves towards exposure. Although she knows her three-year-old daughter, Mia, is no longer truly ill, she keeps her hospitalised anyway, not for the child’s sake, but for her own relief. For Tarisa, the presence of doctors and nurses produces calm not because her daughter is in danger, but because someone else is finally working in her place. As tests confirm Mia’s health, Tarisa’s anxiety escalates. Good news becomes catastrophic. The outer and inner narratives refuse to align, and that refusal is the story.

Readers sometimes tell me they were surprised by how eventful the novel felt, given how little “happens”. They often cite scenes set in libraries, dance classes, or school drop-offs, moments that resemble ordinary life. Film taught me to trust that these spaces are not empty. The ordinary is where psychic drama quietly thrives, if one learns how to look, and how to write it.

Although I never formally specialised in film, my background studying and teaching text-to-film adaptations trained me to watch attentively. Now, when I take breaks from writing, I watch not for spectacle but for permission: to linger, to trust silence, and to let the body carry meaning when language fails. It has been some time since I last watched All Is Well, but I remain on the lookout for films that invite this kind of attention, works that continue to remind me how to give my meditative instincts a narrative spine.

How to cite: Songkaeo, Thammika. “Filmic Silence and the Speaking Body in the Novel.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 17 Jan. 2025, chajournal.com/2026/01/17/filmic-silence.

Thammika Songkaeo is a transnational novelist, non-fiction writer, and film producer of Thai origin. Stamford Hospital is her debut novel, following her nomination to the Bread Loaf Environmental Writers’ Conference, which she attended on a Katharine Bakeless Nason Scholarship, a Graduate Fellowship in Comparative Literature at the University of Texas at Austin, and a grant from the Smithsonian Freer|Sackler Galleries. She received Highest Honours for her study of French literature at Williams College and earned an MFA in Creative Nonfiction from the Vermont College of Fine Arts, before becoming a Storytelling grantee of the National Geographic Society in 2022. Her work seeks to illuminate a range of globally resonant—often “taboo”—themes. [All contributions by Thammika Songkaeo.]