茶 FIRST IMPRESSIONS

茶 REVIEW OF BOOKS & FILMS

[ESSAY] “What is an Orange? Reading Gillian Sze’s An Orange, A Syllable” by Robert Black

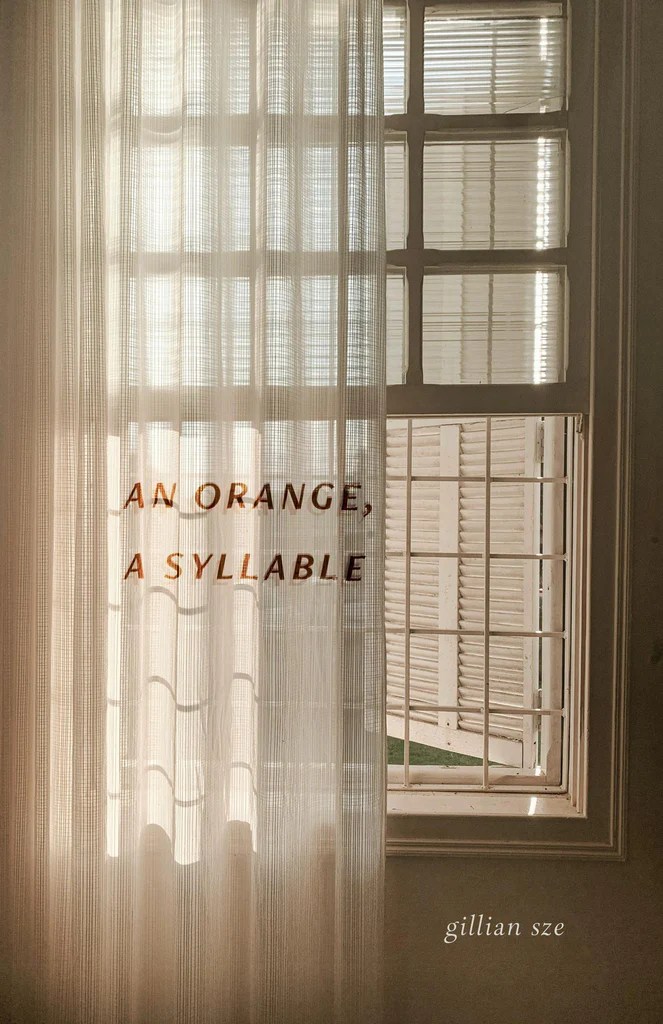

Gillian Sze, An Orange, A Syllable, ECW Press, 2025. 88 pgs.

What Is an origin?

A word, a geometric shape of light, a grey shadow personed within a frame, a movement hidden in the corners of a home emptied of the recognisable, a woman’s back turned towards a window, a child bathing in a tub with a toy whale clenched in its fist, the blank postcards a partner buys on a trip, their very whiteness housing all the potential of love, given unworded.

The light on the threshold names the world.

The weeds in the garden, the birds cloistered in the trees, the scent of an orange on a child’s lips, the bloom held on the tongue in the afternoon, the citrus peel’s scent as the nature of speech.

Loss, loneliness, the languor of love arrive in the shape of what is missing.

The mis-said and misapprehended meaning that hangs between partners on a doorstep, the poem that turns into a shell of prose. Where does the world of naming originate?

The speech we cling to, the way a child teethes on language, the organic sloppiness of our verbal observations, the failure to pinpoint accuracy or to succeed in remembering, the misrepresentation of adults when we fail to recognise or countenance the misunderstood. Is this at the heart of language, and of each of us?

These are some of the questions that lie at the heart of Canadian poet Gillian Sze’s remarkably beautiful new book, An Orange, A Syllable, a work that marries prose poetry with short, poetically inflected philosophical essays examining the nature of language, motherhood, childhood, art, and the bonds between a couple seeking meaning in their lives. At the heart of the book, Sze measures love through the lacuna of language, both her own and the world’s. It is a rich and thoughtful book that searches for meaning amid the confusion that permeates the quotidian life of a household.

)

As Sze describes in her prose poems, we fail even in our verbal abundance, our ideas drawn into an architecture of assumptions built from certainties we purport to be accurate, when in fact their essence, and that of the visible world, is collapsing.

Piece by piece I erect a structure that piece by piece you take apart. Together, we accomplish nothing.

Rauschenberg asked for a drawing from de Kooning and, upon receiving it, erased it. “But empty space tingles the desire to know.”

The child suckling on new words intuits a richer poetry of meaning and description, the palimpsest of the missing which, even in its inaccuracy, reveals something accurate through erasure. Meaning runs out the door the moment we begin to tie it down.

Is this the nature of communication, the nature of writing, the nature of constructing the world through unreal mediums? Is this the nature of love? Of learning? Of being a poet? Of being? Inaccuracy darts forward with a quiver of words strapped to its shoulder.

Where does language’s beginning house itself: in the back of a child’s throat, in the silence of a painting, in the chasm of communication between people straining to find meaning and connection in their marriage, in a child’s late-night fit in a back room, in the appearance of winter light falling from the darkness above in small, twirling flakes?

To go wordless, or abundant in our inaccuracies?

)

An Orange, A Syllable tackles the nature of language and awareness through a series of short, paragraph-length poems and philosophical observations. These range from an exploration of how poetry originates in the way a child names the world to an examination of how a child’s inaccurate naming of objects finds its mirror in adult life, as couples attempt to connect through persistent failures of mutual understanding and of apprehending the world.

The child:

Baby language, I soon found out, was catachrestic…. In the tub, she would point to the eye of the toy whale and say, Moon. She would clamber up the step stool and say, Tree. And when the child pointed to the cracks in the floorboards, she would say, Hole, followed by Ow…. Point to the circles in the rug and say, Hole. Ow. All was lace. From the child’s small mouth, she undid the world around me.

The adult couple:

Another fight, another footnote. These days everything between us is marginal.

Late in the book, after describing the clumsy distance between partners, Sze receives a postcard of a painting by the Danish painter Vilhelm Hammershøi, which prompts an investigation into the meaning of his enigmatic work. Hammershøi’s oeuvre consists of painting absence within the real, the unreal rendered into the actual spaces of the rooms of his home. Again and again, pictorial emptiness captures absence, of love, of language, of meaning, of certainty, embodying despair or longing.

His depictions of light occupying rooms made corporeal prioritise themselves over the human figures that occasionally appear within them. His work stands as an inversion of Vermeer, who privileges the human figure and action within a silence suffused with magnificent light. Hammershøi paints the unseen, perhaps the incomprehensible, through an absence of recognisable markers, most notably in the withholding of his wife’s face. His paintings enact the same palimpsest that lies at the core of linguistic expression: the life behind words, the face we cannot see from behind, the erasure of the drawing, the disappearance of memory and the stains left in its wake.

But do words that outline the world prepare us to truly see?

Hammershøi’s paintings and Sze’s investigations alike seek to understand this question, to describe the presence of what cannot be fully understood or grasped, to write of moments that cannot be wholly encapsulated by paint or word. They confront the stubborn inability of language to cement what we desire to know, its thorny resistance to certainty.

Sze’s commitment to questioning, and her refusal to turn towards certainty, to accept both the blank postcards and the back of the beloved, may be how she comes to understand the nature of love and of writing.

Her reluctance to define or encapsulate a person’s depiction or representation is connected to the way a child’s accumulation of language initially refuses adult definitions. What is the truth of a hole in a sock, the hurt contained in a hole, or the origin of snow?

Height? Emotion? Imagination?

Sze examines these questions alongside the nature of romantic relationships mediated by language, as partners struggle to recognise their failures of communication. The failure of language may, in fact, best secure meaning within relationships and desire, and within the hope that a couple might understand one another and the life they share. Though language resists accuracy, the failure to understand or to be understood may itself be the nature of love.

Sze delves unapologetically into linguistic failure and into the assumption, particularly within romantic relationships, that recognition is possible if only the right words are found. Perhaps, as Sze suggests, it is failure and misnaming that reveal what is possible in love, just as a child’s invented malapropisms convey a deeper poetry.

)

Can two people who love one another ever understand one another accurately? Why do parents fail to understand their child’s fits and desires? Is language uninterested in accuracy, as children often demonstrate, or does it exist beyond accuracy altogether? Why do children not rely on linguistic certainty to measure and seek the world in the way adults long to do? Why are they unencumbered by this need? Perhaps this question lies at the heart of poetry and of meaning.

This is what Sze’s book explores and risks at its boldest: the pursuit of the heart of language.

Sze is a poet, and poets rely on words, depending on form to shape meaning from an often unreconstructible and unknowable world. To continue, to ballast a life and a family, we must shape meaning through language, even when it fails us. When the utility and assurance of words fall away, what remains? What does the poet have to work with, if not words and meaning?

Sze interrogates words and our reliance upon them for comprehension. This fearlessness is what makes the intelligence of her book so compelling. She refuses to romanticise connection and resists the suggestion that linguistic intensity can remedy the grief of unknowing. Instead, absence renders the beauty of the quotidian legible, recognisable, and full of meaning. This holds true for Sze as a poet, a partner, a parent, and a person.

Language is, in the end, our origin.

Beginning as small bodies of hunger, we long for that through which we might explain the world in our endless search.

In a beautiful moment halfway through the book, a mother and daughter press their faces against a window in winter, watching snow fall and searching for its origin, the birthplace of snowflakes:

…Nowhere else to look but skyward. We try always to find that first point, the highest start. But we can see only where the streetlight shines. It’s not snow we see, it’s the instances of light…. Between the two we can measure something that feels like right now, a forever away of time.

A forever away.

Sze’s fluid agility with metaphor and musicality expands the scope of her questions, suggesting that wherever she locates them, in the back of a child’s throat, in the dim corners of a silent room, in the vacant above teeming with light falling on a quiet evening, these are the sites that sustain us through absence.

What is an orange in the mouth of a child?

The origin emerges when the mouth, agape, utters and wrestles sound into the shape of meaning, the shape of the fruit and its abundant scent, the shape of snow falling late at night, the shape of two people standing on a threshold, wordless yet of the world, together, the love for and of the world, the shape of first words and first mistakes that are, in fact, each of us.

Absence, the unrecognisable, the inaccurate, these form the domain of language, of love, and of life, where language and absence become one.

The future we, always held in the mouths of the unborn.

How to cite: Black, Robert. “What is an Orange? A Review of Gillian Sze’s An Orange, A Syllable.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 12 jan. 2026, chajournal.com/2026/01/12/an-orange.

Born in California, Robert Black is an award-winning Canadian poet and photographer who resides in Toronto, Canada. Having lived in seven countries, including part of his childhood in Taipei, Taiwan, his work often explores bifurcated identity and the rootlessness of language. His poetry and short stories have been published in the United States, Canada, France, Russia, Spain, Argentina, the United Kingdom, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Japan, and Australia. He has been a finalist for the CBC National Poetry Award and for the OmniPress Book Award. He is currently seeking a publisher for his first poetry manuscript and is working on a second poetry collection, as well as a children’s book. [All contributions by Robert Black.]