茶 FIRST IMPRESSIONS

茶 REVIEW OF BOOKS & FILMS

Editor’s note: In Hongwei Bao’s new essay, Pillion (2025), directed by Harry Lighton and adapted from Adam Mars-Jones’s 2020 novella Box Hill, becomes a lens for exploring queer biker cinema, kink cultures, and consent. Situating the film within historical traditions, Bao assesses its aesthetics, politics, and limits, offering nuanced guidance for audiences, newcomers to fetish communities, and filmmakers seeking responsible, sex-positive representation on screen.

[ESSAY] “Geared Up for Pillion” by Hongwei Bao

Click HERE to read all entries in Cha on Pillion & Box Hill.

Harry Lighton (director), Pillion, 2025. 103 min.

The public screening of the film Pillion (dir. Harry Lighton, 2025) has become an event in itself. At the film’s première at Cannes and at its public screenings across various international film festivals, Alexander Skarsgård’s fashion choices, involving leather and fetish gear, have attracted considerable media attention. Equally striking has been the presence of leather clad men carrying fetish paraphernalia such as chains, collars, and pup masks, represented by members of the GBMCC (Gay Bikers Motorcycle Club) at Cannes and the BFI London Film Festival, and by the SLM Stockholm at the Stockholm International Film Festival.

Following the film’s theatrical release in UK cinemas on 28 November 2025, several venues have curated fetish friendly screening events. These include a “geared up” screening of the film at the BFI London, in which “fetish gear (leather, biker, pup, etc.) and biker gear is encouraged”, and a screening at The Arzner, London, where “chains, whips, leather, whatever you desire are all welcome”, both held on the evening of 29 November.

What is Pillion about, and how does it relate to the LGBTQIA+ and kink communities? How does Pillion represent kink experiences, and does it do justice to the community it portrays? What should one consider if they wish to attend a Pillion screening in gear, or if they simply wish to learn more about kink and kink communities? This essay offers a brief introduction to kink cultures, practices, and communities, using Pillion as an anchor point.

o

Pillion: “A Gay Kinky Biker Movie“

Based on Adam Mars-Jones’s 2020 novella Box Hill and directed by British filmmaker Harry Lighton, Pillion is an unconventional queer romantic comedy, sometimes described as a “dom-com”, set in contemporary Britain. The film depicts a love story between an introverted young man, Colin, performed by Harry Melling, and a handsome, charismatic gay biker, Ray, performed by Alexander Skarsgård. Colin voluntarily submits to Ray and enters a 24/7 Total Power Exchange relationship. While their relationship is accepted by the gay biker community to which they belong, it is frowned upon by Colin’s mother, who perceives it as exploitative and abusive, leading to a series of compelling conflicts.

Gaywelshbiker, who appears in the film as a human pup, describes Pillion on social media as a “gay kinky biker movie”. The film features an abundance of biker leather, and its cinematography effectively immerses the audience in the embodied experience of riding a motorcycle, vividly capturing speed, movement, and physical proximity (see my review of the film, “Riding Along”). It also portrays the social life of a gay bikers’ club, where members relax in pubs, race along motorways, and gather at private and outdoor parties. They wear leather, rubber, latex, sports gear, chest harnesses, padlocked chains, and pup masks. The film includes explicit sex scenes involving oral sex, spitting, rimming, and fucking, and is therefore likely to alienate some viewers (see my discussion of the film, “The Burden of Representation”). These scenes do not appear obtrusive; rather, they function as an organic component of the narrative and support character development. With virtuoso performances, sleek cinematography, and memorable musical selections, the film is marked by a distinct indie aesthetic while remaining grounded in the familiar conventions of the romantic comedy genre.

o

Gay Bikers on Screen

Both born at the end of the nineteenth century as modern technologies, cinema and motorbikes have shared an intimate relationship in shaping the modern experience of time, speed, and sensation. The history of cinema is deeply entangled with the histories of youth culture, counterculture, and dissident sexualities. Admittedly, not all bikers are gay, and not all LGBTQIA+ people are interested in kink. However, the figure of the “gay kinky biker” has existed as a powerful trope since the 1940s. The representation of the gay kinky biker in Pillion is best understood within the history of cinema, particularly in relation to earlier “biker films” such as The Wild One (dir. László Benedek, 1955), Scorpio Rising (dir. Kenneth Anger, 1963), and The Leather Boys (dir. Sidney J. Furie, 1964).

The 1955 American crime film The Wild One, directed by László Benedek, cemented the association between motorbikes, leather, masculinity, and youth counterculture. The gang leader Johnny, performed by Marlon Brando, who was known to be bisexual, clad in a leather jacket later dubbed the Marlon Brando leather jacket and riding a motorbike, became a cultural icon of post Second World War countercultures. The iconic Marlon Brando poster later appeared in the film Scorpio Rising.

Scorpio Rising is a 1963 short film directed by the American queer filmmaker Kenneth Anger. It is credited with sparking a major fashion fad for biker gear in New York and beyond. The film portrays a group of bikers on a night out and features homosexuality, leather, drugs, motorbikes, and the occult. This experimental work is widely regarded as a precursor to the modern music video and marks the emergence of the mix tape approach to filmmaking, namely the overlaying of images with a popular music soundtrack. The almost fetishistic camera gaze amplifies the appeal of metal, leather, and the nude male body. Notably, the film includes Peggy March’s hit song “I Will Follow Him” on its soundtrack.

British biker culture in the 1960s was closely intertwined with the rockers subculture. Rockers, also known as leather boys or ton up boys, were young people of working class origin who followed rock and roll music and rode motorbikes at high speeds. They formed part of post war British subcultures, and their clashes with Mods in seaside towns such as Brighton and Margate in 1964 generated widespread media sensationalism and moral panic. The Leather Boys is a 1964 British drama film directed by Sidney J. Furie and based on the 1961 novel by Gillian Freeman, who published the book under the pen name Eliot George. Set in East London and marked by British kitchen sink realism, the film engages with motorbikes, homosexuality, criminality, and working class masculinity. Its depiction of same sex intimacy was significantly subdued in comparison with the novel. In the film, most bikers are straight, with the exception of Pete, who is portrayed as actively seducing the heterosexually married biker Reggie. The female lead Dot’s derogatory taunt of the two men as “queers” reflects the public hostility towards gay people at the time. Trump Engineering, a British motorcycle manufacturer, refused to supply bikes for the production due to the film’s queer subject matter. Despite its portrayal of homophobia, the film nevertheless remains a daring example of queer cinema for its period.

As if paying tribute to earlier biker films such as Scorpio Rising, Harry Lighton opens his 2025 film Pillion with the Italian version of the song “I Will Follow Him”, titled “Chariot” (Sul Mio Carro), while the English version is used in the film’s official teaser. In contrast to the angry straight biker Johnny in The Wild One and the isolated gay biker in The Leather Boys, Pillion depicts a young man, Colin, being inducted into a gay biker community, presenting gay bikers as a collective that forms strong social bonds and lives an unapologetically authentic lifestyle. The comparison between these biker films gestures towards the symbolic function of gay bikers as representatives of alternative lifestyles and communities that resist dominant sexual and social norms. At the same time, the differences among the films reveal shifts in public attitudes towards LGBTQIA+ people and demonstrate how biker communities have become increasingly queer friendly over time.

o

Representing Kink:

On Limits, Boundaries and Non-Verbal Consent

Pillion has been celebrated for its bold and authentic representation of kink communities and lifestyles. Writing for The Guardian, Barry Levitt asked members of kink communities about the authenticity of kink representation in Pillion, and the responses were overwhelmingly positive. In the interview, Luca (29, Oxford) comments that “Pillion nailed the idea of BDSM and kink being about experimentation and self-exploration, and not just strictly in bed”. Homme de Cuir, a steel artist and designer whose work appears in the film, views it as a celebration of the kink community, observing that “there’s so much warmth and so much humanity in Pillion“. KrugerAfterDark, a fetish community online journal, similarly praises the film as a much needed corrective to earlier BDSM representations, in which “BDSM or fetish are very often reduced on celluloid to thriller and horror genre psychopathic sadists, or the much maligned stereotypical gimp in the basement”.

Questions of consent and boundary crossing sit at the centre of many discussions of the film, particularly given the guiding principle of BDSM, namely “safe, sane and consensual”. In the same Guardian interview, Dr Lori Beth Bisbey, a GSRD therapist, sex and intimacy coach, and psychologist, notes that there “isn’t a single consent conversation in the film”, perhaps because extended negotiations between Colin and Ray could appear tedious on screen and reduce narrative suspense. Consent, however, is pervasive throughout the film and manifests in multiple forms, ranging from Colin’s shout of “thank you” to Ray after their first alleyway hook up, to his embarrassed response, “that sounds like a plan”, following Ray’s suggestion of a butt plug. It is further expressed through Colin’s silent compliance with Ray’s instructions, his voluntary return to Ray each evening, which he is not compelled to do as a consenting adult with a gay friendly parental home, and his defence of Ray before his parents, as well as his pride in identifying as a sub in front of his colleagues. Within the film’s cinematic grammar, consent is articulated both verbally and non verbally.

BDSM also expands conventional understandings of consent as an explicitly verbal agreement between transparent, rational, and autonomous subjects. As Judith Butler suggests, one does not always know in advance who one is or what one desires; rather, the self is explored and understood through action and within evolving social contexts. Viewed in this way, consent is not an a priori condition but a dynamic process, continually negotiated between those involved and shaped by their specific social locations. This is precisely the process Colin undergoes in the film, in relation to Ray and through his ongoing assessment of each situation as it unfolds. Consent is thus relational and dynamic, rather than individualistic and static.

The film is not without criticism. Ben, a member of London’s fetish community, writes on Letterboxd that despite evident progress in kink representation, the film reproduces several clichéd tropes associated with BDSM relationships. Most significantly, he argues that it fails to depict a healthy kink dynamic: “I’m a bit tired of how every protocol sub in film lacks agency in their real life and was born for nothing more than to follow, and how every protocol dom in film is actually emotionally repressed and afraid of connection, and how every kink dynamic in film is actually just a really unhealthy relationship with attractive dressing.” Ben also highlights the absence of clear communication and boundaries on the part of both characters, which ultimately renders the relationship unsustainable. “Colin’s continuous breaching of Ray’s set boundaries is often played as tragic or as though there’s yearning behind it as opposed to it being a breaching of boundaries that keep Ray comfortable.” While many viewers may side with Colin because of his perceived subordinate status, Colin bears as much responsibility for maintaining the dynamic as Ray does. Ultimately, the film centres on consent, limits, and boundaries, demonstrating both their necessity and the ways in which they can become complicated in lived relationships.

The relationship between Colin and Ray is distinctive, shaped by their personalities, past experiences, and shared encounters. Colin enters the dynamic as an introverted, inexperienced, first time sub, hesitant to articulate his needs or assert himself. Ray’s history remains largely opaque, aside from the three women’s names tattooed on his chest, which may gesture towards psychological trauma from earlier relationships as well as discomfort with his own sexuality, a factor that also explains his prolonged avoidance of physical intimacy with Colin. Although their relationship resembles a protocol dom sub dynamic, particularly within the Old Guard tradition, it is not presented as the only model within the kink community. The film also depicts alternative dynamics, such as that of Kevin, performed by Jake Shears of Scissor Sisters, and his dom, whose relationship is more casual and openly affectionate, including kissing and hugging. As Alexander Skarsgård remarks in a PinkNews interview, “We wanted those scenes with the whole gang to feel authentic but it was also important to distinguish the couples within this group because we’re not carbon copies of each other. For example, Colin and Ray don’t kiss. But that doesn’t mean it’s a rule within the group obviously.” Pillion thus foregrounds the diversity of kink identities and relationships and, in doing so, challenges clichéd stereotypes and monolithic representations of kink on screen.

Pillion may not offer a flawless representation of kink, but it nonetheless marks a significant advance in comparison with earlier cinematic portrayals. It gestures towards the possibility of more complex and nuanced representations in the near future. What filmmakers can learn from the film lies in its celebration of diverse and authentic kink experiences, as well as in its reciprocal relationship with kink communities, extending from production through to reception.

o

Geared Up for Pillion

Reviewing the film for The Guardian, Peter Bradshaw describes Pillion as “BDSM Wallace and Gromit” and as “what Fifty Shades of Grey should have been”. Although the sadomasochistic dimension of the narrative is less visibly foregrounded on screen, Pillion is saturated with fetish, fetish for leather, for motorbikes, and for men. Oxford Learner’s Dictionaries define fetish as “(1) the fact that a person spends too much time doing or thinking about a particular thing or thinks that it is more important than it really is; (2) the fact of getting sexual pleasure from a particular object; (3) an object that some people worship because they believe that it has magic powers.” These definitions tend to cast fetish in a negative light, but this need not be the case. In Pillion, Colin’s love for Ray can be understood as an obsession and therefore as a form of fetish. Ray’s attachment to leather and motorbikes carries both sexual and spiritual connotations. Fetish is represented in multiple ways throughout the film: in the manner in which Ray’s tight fitting leather reveals the contours of his body and emanates sexual appeal, in the methodical care with which he washes and rides his motorbike, and in the admiring gaze Colin directs towards him. Fetish is ultimately celebrated in the film as an authentic experience and a genuine expression of the self.

Fetish is often perceived as “too much” within heteronormative and sex negative cultures. For people of marginalised genders and sexualities, however, fetish can function as a form of liberation and empowerment, as a way of life, and as a means of finding friendship, intimacy, and community. The French philosopher Michel Foucault’s essay “Friendship as a Way of Life” and the American feminist thinker Audre Lorde’s essay “Uses of the Erotic” both point towards productive and sex positive approaches to sexuality, pleasure, and collective belonging.

Leather, kink, and BDSM communities have long existed in urban centres. The post Second World War period witnessed a proliferation of biker, leather, and BDSM clubs, bars, and organisations. Among the most famous venues are The Eagle in San Francisco, Quälgeist in Berlin, SLM Copenhagen, and the now defunct The Backstreet in London. Major venues and organisations also host Mr Leather or Mr Fetish contests, whose winners are often expected to serve as community leaders by promoting and supporting their communities. Some of the best known kink events include Darklands Antwerp Fetish Festival, Fetish Week London, the Folsom Street Fair in San Francisco, Folsom Europe Berlin, and Maspalomas Fetish Week in Gran Canaria, Spain. Folsom Europe Street Fair 2025 attracted 20,000 visitors from around the world, transforming Berlin’s Schöneberg district into a carnival for kinksters.

In recent years, aided by the Internet and social media, kink communities have expanded rapidly. These communities are not confined to lesbian, gay, and bisexual people but also include heterosexual and trans identifying participants. Recon is among the most popular apps for gay and bisexual men interested in fetish, while FetLife is one of the most widely used platforms for kink communities across genders and sexualities. The understanding of fetish has also broadened significantly in recent decades. According to the Fetish Week London website, one may be drawn to a wide range of kinks, including leather, rubber, sports, skinhead, uniform, military, and pup play. Among Generation Z, pup play has emerged as one of the most popular kink practices.

For newcomers, one of the best ways to meet fellow kinksters is to attend a local leather or fetish social, often referred to as a “munch”. These gatherings usually take place in public venues such as fetish friendly pubs, bars, or community centres. While there is typically no strict dress code for such events, wearing fetish gear is often encouraged. For fetish parties held in private clubs, however, attendees are advised to read event information carefully and familiarise themselves with the relevant dress and behavioural codes. Historically, fetish communities have relied on coded forms of communication, particularly during periods when homosexuality was criminalised and kink practices were forced underground. Handkerchiefs or bandanas of different colours signal specific sexual interests, while wearing chains or hankies on the left traditionally suggests a dominant role and on the right a submissive role. John Pendal’s blog article “First Time on the Scene” offers useful guidance for newcomers to leather bars within the Old Guard tradition, although some advice may appear outdated in contemporary contexts. Organisations such as London Leathermen and Klub Verboten provide club rules tailored to present day audiences. Across all venues and events, core principles including consent, safety, respect for boundaries, and privacy remain paramount.

One does not need to get geared up to attend Pillion, although doing so is more than welcome. For a film that celebrates kink experience, wearing publicly acceptable fetish gear can feel appropriate where venue policies allow. Above all, attending a Pillion screening requires courtesy towards venue staff and fellow cinemagoers, an open mind, and a willingness to embrace both surprise and emotional intensity along what may be a challenging but rewarding journey.

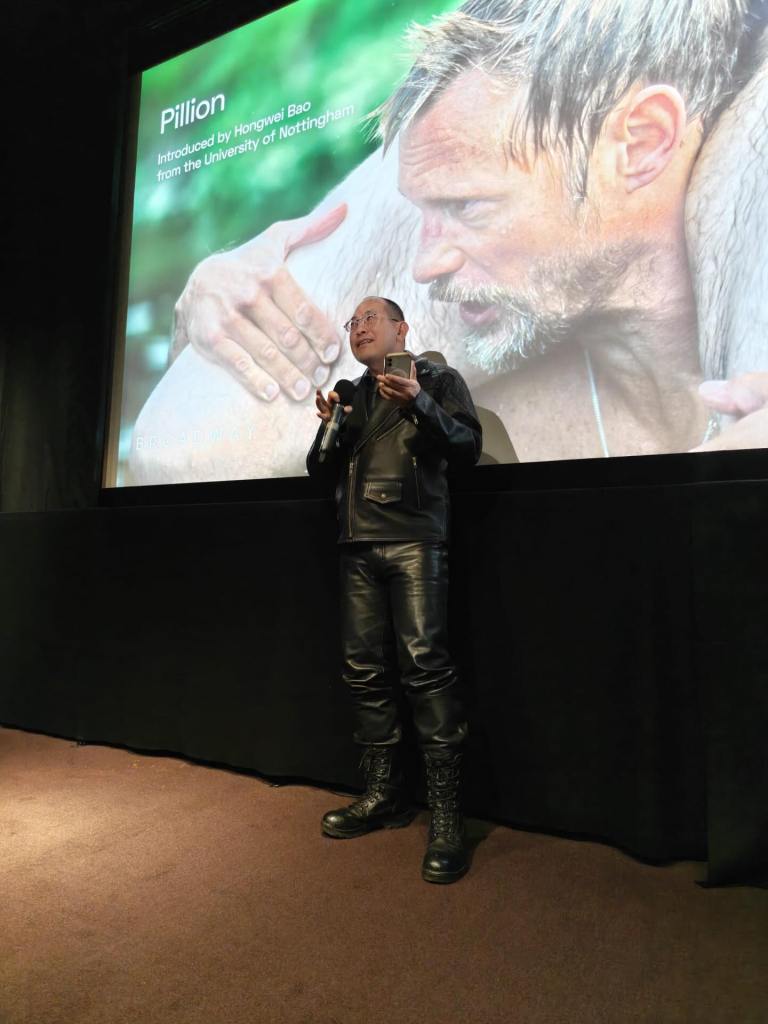

Hongwei Bao introduced Pillion, wearing bike leathers, at Broadway Nottingham on 2 December 2025

How to cite: Bao, Hongwei. “Geared Up for Pillion.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 10 Jan. 2026, chajournal.com/2026/01/10/geared.

Hongwei Bao is a queer Chinese writer, translator and academic based in Nottingham, UK. He is the author of Queer China: Lesbian and Gay Literature and Visual Culture under Postsocialism (Routledge, 2020) and Queering the Asian Diaspora (Sage, 2025) and co-editor of Queer Literature in the Sinosphere (Bloomsbury, 2024). His poetry books include The Passion of the Rabbit God (Valley Press, 2024) and Dream of the Orchid Pavilion (Big White Shed, 2024). [All contributions by Hongwei Bao.]