Editor’s note: Cleo Li-Schwartz’s essay entwines personal pilgrimage and critical meditation, reading Berlin as a palimpsest of Jewish memory, Cold-War fracture, and inherited displacement. Moving through memorials, friendships, and borders, the narrator unsettles any stable present. The essay later turns to Leung Ping-kwan, a Hong Kong poet and essayist renowned for his meditations on history, migration, and cultural interstices, whose Berlin writings retrospectively frame these encounters. Through his poetics of the interstice, Berlin emerges as a provisional space for thinking memory, language, and belonging across generations and geographies.

[ESSAY] “Walking with Leung Ping-kwan: Berlin, Memory, and the Interstice” by Cleo Li-Schwartz

)

Ramble 1

When walking in Berlin, I always feel that I traverse segment after segment of history with my own two feet. —Leung Ping-kwan, Walking in Berlin1

我在柏林走路老覺得自己在用雙腳走過一段一段歷史。——也斯《在柏林走路》

Berlin is a city whose history and very spatiality invite reflections on memory, in my case both personal and political.

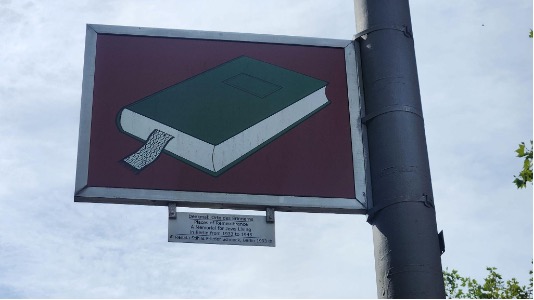

On my first visit there last August, I met B, an old friend of my father’s whom he had not seen in 35 years. She took me on a walk through Schöneberg, once an enclave of affluent Berlin Jewish life, to see Renata Stih and Frieder Schnock’s fragmented memorial “Places of Remembrances,” eighty signs scattered throughout the neighbourhood, each of which is emblazoned with the text of an anti-Jewish law and a corresponding artist’s image. Installed in 1993, when these smaller-scale memorial projects were just beginning, and controversial for both their bluntness and their placement, these signs reinscribe the texts of oppression above the heads of contemporary passersby. In fact, when Stih and Schnock first set about installing their work, the police dismantled and confiscated their placards. “Art or no art, the limits of good taste have been overstepped.” So said the State Secretary. A look up can be a look towards the past, sometimes an undesired one.

B is also an art journalist, and so it was that I found myself at dinner with Stih and Schnock that evening at their home and studio in Potsdamer Platz. “The Places of Remembrance,” for me so freshly emblazoned, were for them a distant memory of a project commissioned over 25 years ago. They recalled that at the time many were opposed; one curator in Munich declared that all such sparks of memory should be housed in a museum, not on the street, where they might intrude uncomfortably on daily life. But is that not the point of “never again,” and of Vergangenheitsaufarbeitung (working through the past), that we must be reminded of these ugly pasts wherever we turn? The unsettling bullet points of legalese that presaged the Final Solution certainly do that. The Jewish Museum in Berlin now has a similar exhibition, which collects the text of every single anti-Jewish law in one vast room. Its effect is equally chilling but different, more viscerally overwhelming yet sealed off from the everyday. The infiltration of the everyday, of quiet, now-tranquil Schöneberg, is the power of Stih and Schnock’s installation.

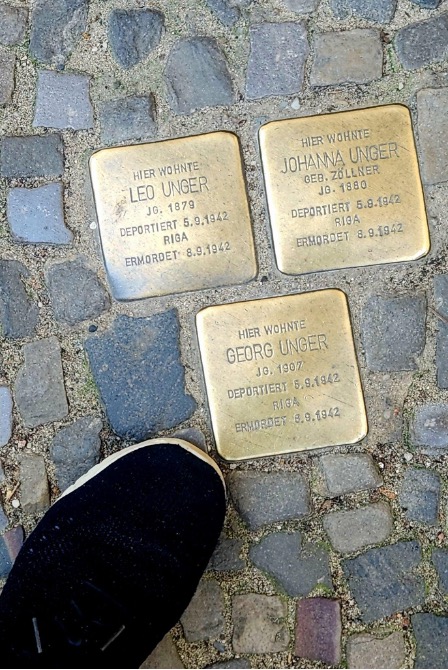

These days, a look up in Schöneberg can be accompanied by a look down. In the intervening years, Stolpersteine, or “stumbling stones,” which commemorate individual deported citizens at their last known address, have populated the city, including Schöneberg. On this first trip to Berlin they were among the many visible traces of an ugly past that scars the city. I was staying on the other side of town, in what was once East Berlin, and it took me three days of coming and going to notice the stumbling stones inlaid right next door to my apartment. Once I did, they were impossible to forget.

In a roundabout sense, it was those very stones that had brought me to Berlin in the first place. The summer before, in Washington, DC, I had attended a reading by Jeremy Eichler, the author of the astonishing Time’s Echo, a cultural history of the music of Holocaust remembrance. There I struck up a conversation with the remarkable H, newly arrived in Washington from Berlin, who told me about her work bringing descendants of those memorialised to visit the stones as they were inlaid. In fact, our conversation began when I told her my story of acquiring Austrian citizenship through my Viennese Jewish great-grandmother, Anna. It was a two-year process that took me into the family archives and into a painful national history, one that remained embittering for Anna until her last days, during which, my father tells me, she forgot every word of English she had ever learned and could speak only German. As I told H, when we visited the site of her apartment building in Vienna earlier that summer, we found virtually no trace of her community’s presence in their historical neighbourhood, only in the Jewish Museum and in memorials elsewhere in the city. H and her husband agreed that there was more work to be done and urged me to visit Berlin.

Even to the untrained eye, Berlin’s architecture bears the traces of its many chapters. They are found in the ruins of Anhalter Bahnhof, a train station from which nearly 10,000 Berlin Jews were deported between 1941 and 1945, in the invisible line of what was once the Wall, still perceptible to many, which B confidently traced from the roof of her newspaper’s building, and in buildings whose tops were blown off and later reconstructed in a wholly different architectural style.

On my second trip to this variegated city, I stayed with B. I took a trek out to the Spandau Fortress to see Monuments Unveiled, an exhibition that brings together a selection of monuments that once graced, or marred, the city’s streets and squares, from Prussian relics to Nazi-commissioned statues intended for Speer’s New Reich Chancellery, and even the disembodied, gargantuan head of Vladimir Lenin. It was an echo of a common occurrence on the streets of the city itself, where, for example, an encounter with Martin Luther can be followed in rapid succession by a visit to the Marx-Engels Forum. It was jarring to see works that would normally be surrounded by swirls of pedestrians and vehicles, leaves and songbirds, placed instead in the relatively sterile space of a hushed gallery. Equally jarring, I realised, was the injunction at the exhibition’s entrance that “it is permissible to touch most of the objects.” There was something strange about laying hands on a work neatly displayed and itemised within the space of a gallery. It reminded me of the feeling of cradling a 4,000-year-old piece of jade in my hands the previous weekend in London, a disorientation of space, time, and sensation.

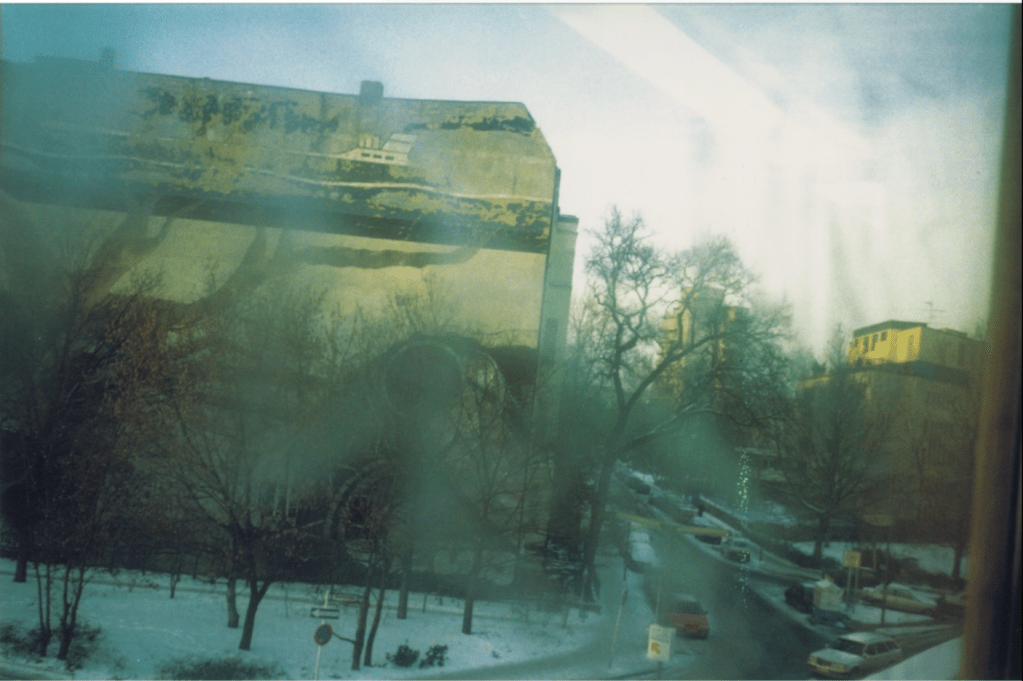

Every morning, B’s phone sends her a selection of random images from her camera reel. Often, she says, she does not remember when or where she took them, or even what they depict. “I photograph a lot of art, and sometimes art looks like reality, and reality looks like…” She trails off, but I grasp the point.

B knew my father long before I existed, before the Berlin Wall itself came down, and when he was not much older than I am now. I meant to ask her a question or two about the past, but somehow the moment never quite arrived.

Sometime later, my father tells me that B once met my grandfather, Anna’s son, at his house on Long Island, a house that I would later dub “the truck-house” for its delightful preponderance of plastic toy trucks.

This is a conversation I must have with her, next time in Berlin.

)

Ramble 2

My consciousness of the powers of Berlin and of Leung Ping-kwan’s writing bloomed at more or less the same time. A Hong Kong writer known for his keen attention to the fragmentations of history and the rich promise of cultural and culinary interchange, he wrote the words that open part one of this essay, expressing the sense that a walk through this city was a walk through history, in 1998. It was a year after Hong Kong’s handover to mainland China. It was also a year before I was born in New York City, arguably thanks to two twists of history, Nixon’s visit to Beijing in 1972 and the Tiananmen Square massacre in 1989.

This much is true: in 1998, PK began a residency in Berlin. It was not his first time in the city, but it would be the sojourn during which he produced a wide-ranging collection of essays that muse on his experiences of the city and its surrounds, and on the complicated local histories to be uncovered. He begins his account of Berlin with one of hurried departure from Hong Kong: “走得太匆忙,沒來得及說再見…在飛機上還在想該聯絡而未聯絡的朋友,看著窗外的浮雲,我想像你們又會說:「你也不是第一次這樣了吧?」” [“I left too hurriedly and did not manage to say goodbye… on the plane I was still thinking of friends I needed to stay in touch with but had not. Looking at the floating clouds outside the plane window, I imagine you saying, ‘But this is not the first time you have done this, is it?’”]

In the summer of 2024, I arrived in Berlin after a blur of leavetaking from Washington, D.C., some farewells fully enunciated. I plunged suddenly into the exploration of a city whose history is dark yet pulsing, and chanced to meet a number of Chinese people who had washed up in Berlin for various reasons: a film curator, a visual artist, and a writer from Beijing of some acclaim. All seemed to see Berlin as a haven of sorts, though perhaps only a temporary waystation, one they hoped would stimulate them while they worked out what came next.

That week, Berlin was a kind of waystation for me too. Never completely at home anywhere, that summer I truly had no home, having packed up one apartment in one city and not yet begun a new stint in another. While much of that initial trip was consumed by confronting the more obvious history that haunts Berlin’s streets, the period of Nazi rule and the fate of the city’s Jews, I also sensed its subtler connections to China and to Hong Kong, both through the people I met and the writing I was reading. My father’s friend B told me about a period in her career as an art journalist when she had travelled to China multiple times, usually sent to cover a fashion show or art expo sponsored by a German corporation. The last time she went, Ai Weiwei had been arrested, in fact at a nearby gate as she waited for her flight home to Berlin. She lost her taste for China after that.

I was introduced to that Chinese writer by her ex-husband, an interpreter of German, English, and Chinese, who also lived in Berlin and, in a remarkable twist, right next door to B. I avoided asking too many questions about the dissolution of their marriage, but I sensed the presence of two cleaving narratives shimmering somewhere out there in the city, both bearing some relation to, but not encompassing, that broken relationship. Their young son, a mixed-race child now handed back and forth between them, would presumably have yet a third version of events. His father whispered to me darkly that he insisted on holding on to the child’s passport, lest his mother whisk him back to China overnight.

I remember crossing the Canadian border once without one parent present and being sternly questioned by the authorities about their absence. I no longer remember which parent was missing, the Chinese mother or the American father, or which authority asked all those questions, the American border guards or the Canadian ones. My hunch is that it was the Americans. In any case, we crossed that border, then re-crossed it. The child was not abducted, the family was not severed.

Borders, for PK, are a perennial subject. In his story of the same name (“邊界” in Chinese), he writes about the experience of being a writer and a wanderer, and about the disjunctures of experience such a figure confronts:

How am I to recount this journey to Washington, just as I would recount any journey at all?When I came back to Berlin in 1983, I began telling stories about Paris. In 1990 I had a chance to stay in Berlin and spent my entire time there writing a story about Hong Kong. I wrote about Berlin while I was in New York, and about New York in Washington, D.C.… stories of the past never catch up with the ever-vanishing present. The present constantly alters memory, which is why the quest for the past is such a futile exercise… and yet, yes, history does stick together somehow or other. The past coheres, in its own fashion. And all we can do is speak to the present from its interstices.

我怎樣敘說這趟華盛頓的旅程?正如我怎樣敘說任何一趟旅程?我八三年回到香港以後就在說巴黎的故事,九〇年有機會在柏林一段時間,期間又一直在寫一個香港的故事,後來去到紐約就在寫柏林,去到華盛頓卻開始寫紐約……追記的故事總沒法追上眼前現實,眼前的事又不斷修改我的記憶。追逐過去是徒勞的,以前我老想什麼都可以交代,都可以時空順序,後來發覺這只是一個幻想,歷史黏在一起,我們在隙縫間向現在發言。

One scholar speaks of PK’s sensibility as a kind of “bricolage” poetics. Perhaps it is more to the point to locate his work in the interstices of history and experience, part and parcel of his point of origin, that interstitial city of Hong Kong. “Borders,” like much of PK’s oeuvre, is about searching for a perspective from which to understand one’s writing and one’s travels. It is about bridging distance, but also about acknowledging its existence. Intervention without erasure, the interstice.

Is it appropriate to speak of Berlin and the interstice? An interstice is an intervening space, “especially a very small one.” Berlin itself was once bisected by the brutal scar of a border slicing through its heart. In Kairos, Jenny Erpenbeck writes about the experience of being on the verge of crossing that line: “…now all of a sudden what was inside is outside, and what was ordinary is now cut off from her and no longer visible. Suddenly everything is inverted, topsy-turvy, now she is behind the picture, behind what was once the surface of some unreachable beyond… On the short stride of the station the glass façade cuts off the top of the building from the air outside, which in principle is still Eastern air, but because it gives access to the West is sort of Western air too… is this grey station endowed with the power to hold two different sorts of time, two competing presents, two everyday realities, one serving as the other’s netherworld? But where is she, when she stands on the borderline?” She is perhaps in the interstice of East and West, past and present.

These days, that space of breach has become, like so many other sites, commodified, a tourist checkpoint to be ticked off a list. Borders, however, remain as menacing as ever in their demarcation of the permissible and the forbidden. When I returned home to the US for the first time since the 2024 elections, most of my friends there, those who are not American, had been advised not to leave the country for fear that they would not be allowed to re-cross that bristling nativist border. My own American passport allowed me, shamefacedly, to leave the country in the confidence that I could return if I wished to. One afternoon I saw a meek, unassuming-looking man being arrested in the middle of Dupont Circle in Washington, D.C., and, as the paranoia of the times set in, I wondered whether he had committed some minute border infraction.

Later that day, I saw my friend M., a native Beijinger like my mother, for the first time in a while. Berlin came up, as it often does these days. Berlin reminded me of Beijing, M. said, in its size. She qualified the comparison: like Beijing in the 2000s, with its television towers and lights. “I do not remember the language in Berlin, but I do remember the sound.” And also: “I took the trip at a strange moment, when I was getting close to R.” R. was not there with her in Berlin, yet it was from the space of that city that the two of them drew emotionally closer. M. and R. were married last August, on the last day of my first trip to Berlin.

For me, that summer before the elections is now haunted by two of PK’s poems, products of his brush with the German-speaking world in those years, which I read immediately upon my return from Berlin: “A Haunted House in Berlin” and “Love and Death in Vienna.” Since I am speaking of Berlin, I will include only a fragment of the former:

All those pasts coming back to visit us

those flattened and distorted images in the mirror…

At one time there were secret tunnels in the city

and sentry posts in winter, they won’t easily

be swept away by the brandishing arm of the crane

From the shopping arcade of our desires

A self returns from a foreign land to knock at the door, in his eyes

An expression we find familiar and strange—

Still there? The words I scribbled down

Have turned suddenly into signs I cannot decipher…

The remnants of our blurred memories

call us in a whisper amidst flickering shadows in the city

Shall we stand by the window every morning to embrace old wounds?

Or watch old houses on fashionable streets being torn down

Leaving not a trace? How does one rebuild the ruins?

We shall have to live with our ghosts

那些過去回來尋見我們

镜中壓扁的扭曲形象…

城市裡曾有秘密的隧道

懂點的哨崗,不容易

被揮舞的吊臂所抹平

我們慾望商場下一個異鄉的

自己回來敲門,他有我們

認識不認識的眼神 —

還在那兒嗎?是我寫下的文字

突然變成無法辨識的符號…

………過去模糊記憶的頹垣

在城市幢幢陰影裡低喚我們

每個早晨從窗子擁抱老傷疤?

抑或看時新大街上舊房子拆得

不留痕跡?怎從廢墟翻新?

我們將要學習如何與鬼靈相處

Leung Ping Kwan’s artwork related to “A Haunted House in Berlin”

In Berlin one feels the ghosts very near, flickering just at the edge of the frame.

Perhaps it is the convergence of so many unlikely threads in Berlin that explains my curious affinity for this city, as for Hong Kong, despite not speaking either city’s most native language and having no personal, that is familial, connection to either place. Yet in both Berlin and Hong Kong’s imaginaries I find reflections of my own interests in memory and history, and in the liminal perches between cultures and languages that make life so poignant yet so worth living.

PK took his first trip to Berlin just after the Wall’s fall in 1990, a period in which low personal spirits naturally led him to distant shores. Yet, as he records, from the minglings of East and West in that city emerges a description that could easily apply to Hong Kong: “雙腳卻已經走進曖昧的地段:到底那是在西方還是在東方呢?那舊宅似乎是東邊的風景,但那廣告不又正是來自西邊嗎?” [“I had already stepped into an ambiguous zone: was it the West or the East? That old building seemed to belong to an Eastern landscape, but was not that advertisement clearly from the Western side?”]

Minglings of East and West. I took my second trip to Berlin to see Deutsche Oper Berlin’s new production of Nixon in China, the remarkable John Adams and Alice Goodman opera that depicts the fateful week in 1972 when President Nixon’s visit to Beijing reopened US-China diplomatic relations. More than a “CNN opera,” as it is sometimes pejoratively described, Goodman’s text probes both Chinese and Western sensibilities in ways I am only beginning to understand. My mother, who lived through the Cultural Revolution, once told me that it was Goodman’s setting of Jiang Qing’s aria “I Am the Wife of Mao Zedong” that finally enabled her, after so many years, to grasp this terrifying figure’s psychology: “Let me be / A grain of sand in heaven’s eye / And I shall taste eternal joy.” I went to see this new production with B, who had never seen the opera before and who expressed bewilderment at the dizzying array of visual drivel produced on stage. Strangely, the directors chose to visualise Goodman’s delicate imagery in the crudest possible way. Even more disturbingly, the Chinese characters in the work were depicted as sub-human, almost insect-like. This reminded B of the phrase chinesische Ameisen, “Chinese ants,” a pejorative term used in 1950s and 1960s Germany. The decision to restage this opera at such a moment was certainly an interesting one, and some of the production choices even more so. I later wondered what PK might have made of it, and whether he had ever seen the opera in one of its earlier stagings. Goodman’s text would, I think, have appealed to him in its fine-grained, personal approach to documenting such a historically sweeping meeting of minds.

It was only after my second return from Berlin that I discovered 《在柏林走路》, and only then that I recalled reading Jeffrey Wasserstrom’s linkage of Hong Kong and West Berlin in his slim volume Vigil: Hong Kong on the Brink: “Hong Kong and West Berlin stand at opposite ends of the Eurasian landmass, about as far apart as two cities can be geographically and culturally. And yet for most of the second half of the twentieth century, they were doppelgangers in an important way. Each was a focal point of Cold War tensions, linked by the shared stresses and strains of being battlegrounds between two diametrically opposed ideologies. Hong Kong, like West Berlin, was used as a listening post onto a nearby place.” While Wasserstrom goes on to outline the many ways in which these two places have since diverged, there remains a strange doubling effect between the two Eurasian cities.

It is in his encounters with Berlin’s darkest period that Leung Ping-kwan most evocatively conjures the interstice. On one of his walks, he happens quite by chance upon the book-burning memorial at Bebelplatz, which at the surface level appears to be little more than a hole cut into the ground. Peering through this window, he is transported:

Walking on Friedrichstrasse, on the open space of the square beside the ancient buildings, I unwittingly discovered a small window cut into the surface of the earth. It turned out to be a meticulous art installation, and I twisted my body to peer through the window. This contemporary artist asks us to look carefully into a space that lies outside glimpsable reality. They have dug out an empty room underground and filled it with bookshelves. The number of books that could fill them is exactly the number of books the Nazis burned at this site (2000). This empty bookshelf reminds us of the books that were violently burned and no longer exist. It is true that, if you pay close enough attention to the streets of Berlin, of Hong Kong, of any city, you will see many such caverns and interstices. They remind us of the residues of past violence, injustice, and prejudice, which remain to this day.

我走在腓特列大道菩提大道上,在古老堂皇的建築物旁邊廣場的空地上,無意中發現了地面上的一個小窗口。原來是一件精心的裝置藝術,我彎身從窗口看進去。這位當代藝術家叫我們留神眼前現實之外的一個空間:在地面底下挖了一個空室,放滿了書架,那裡可容的書本數目正是納粹當年在這裡燒去的數目。這空室中的空書架提醒我們當年被暴力焚掉、現已不存在的書。是的,過去柏林、香港,或是任何其他城市的街頭,只要仔細留神,一定也可以看見不少大小不一的洞穴和隙縫,提醒大家從過去殘留到現在的種種暴力、不公和偏見。

Peering into the crevasses of the past, he attempts to make out the hazy lines of a history that exists in between, tracing the reverse contours of historical narrative. On my third visit to the city, I too strained to see the empty shelves below. By then, the glass was smudged, making the task even more difficult. As PK writes later of the Jewish Museum, the interstitial windows of its installation centre the body within the layers of history.

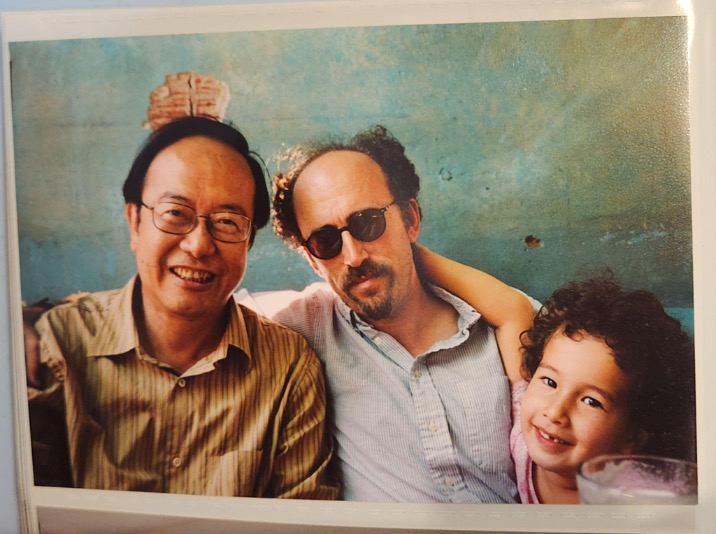

Every encounter, every conversation, leaves a trace. Most often this occurs through memory, but sometimes through a photograph. Recently my mother and I unearthed a photograph of myself, my father, and Leung Ping-kwan, splayed cosily against a mottled turquoise wall whose hue somehow reminds me of a Vietnamese restaurant in the sixth arrondissement of Paris that I failed to relocate the last time I was there. In her familiar, cherished handwriting, my mother has located and dated it for us: Vancouver, August 2004. I have no independent memory of this meeting, but there it is, burning in the archives. Long before my conscious encounter with his words, there we are together, in company, in exchange, in Canada. Was that the same trip during which the guards questioned us because a parent was missing as we crossed the border? No, it cannot have been. My father is in the frame, and my mother remembers taking the photograph.

I always try to visit a cemetery when I am in a new city. These alternate spaces offer a moment of quiet amid the chaos of new encounters, as well as a window into how a place conceives of and honours death. PK writes about visiting a cemetery in Berlin’s Kreuzberg: “我看見盡頭那面牆,一邊是人家的房子,另一邊已是高大的陵墓。換了是中國人的地方,這幾乎是不可能的事。但在這裡,對死亡,以及對生命,顯然保持不同的看法。” [“I looked at the wall at the end of the cemetery. On one side were people’s homes, on the other towering tombstones. This would be almost inconceivable in a Chinese setting. But here, views of death, and of life, are clearly different.”]

Suddenly a scene came back to me from my first trip to Berlin. Wandering into a leafy Jewish cemetery in Prenzlauer Berg, one that for obvious reasons is now more a memorial site than an active burial ground, I looked over the cemetery wall and saw a row of modishly white high-rise buildings. Across that particular wall, the business of life continued. On that beautiful summer day, people dried their clothes on their balconies, hosted friends for tea, and carefully tended their plants. I did not begrudge them the pleasures of daily life. On the contrary, there was something reassuring in the cool, pleasant murmurs of chatter drifting from the space of the living to the space of the dead. Yet I did wonder how often any of those Berliners might chance to glance over the wall to the solemn graves on the other side, and what thoughts might cross their minds in such a moment.

I am in a position now, I think, to have a proper conversation with PK. But it is too late for one conducted face to face. He died in 2013. Now I can only peer over the wall, over the page, hoping to distil something from his texts, to draw them closer, while remaining conscious of the interstices of time, space, and language that separate us.

From right to left: From right to left: this essay’s author (Cleo Li-Schwartz), Leonard Schwartz, and Leung Ping-kwan. Vancouver, Canada, August 2004. Photo by Zhang Er.

The Jewish Cemetery, Schönhauser Allee, Prenzlauer Berg, Berlin, August 2024. Photo by the author.

- The “Walking in Berlin” excerpts are translated by the author, “Borders” is translated by Shuang Shen, and “A Haunted House in Berlin” by Martha Cheung. ↩︎

How to cite: Li-Schwartz, Cleo. “Walking with Leung Ping-kwan: Berlin, Memory, and the Interstice.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 31 Dec. 2025. chajournal.com/2025/12/31/berlin.

Cleo Li-Schwartz is an editor and writer specialising in Chinese-language literature and culture. She earned an MPhil in Chinese Studies at the University of Cambridge and was previously an Associate Editor at The Washington Quarterly in Washington, DC.