茶 FIRST IMPRESSIONS

茶 REVIEW OF BOOKS & FILMS

[ESSAY] “Not A Utopian Land: Rereading the Evenki Culture in Chi Zijian’s novel The Last Quarter of the Moon and Gu Tao’s documentary film The Last Moose of Aoluguya” by Yiwen Liu

✿ Chi Zijian (author), Bruce Humes (translator). The Last Quarter of the Moon 额尔古纳河右岸, Vintage, 2014. 320 pgs.

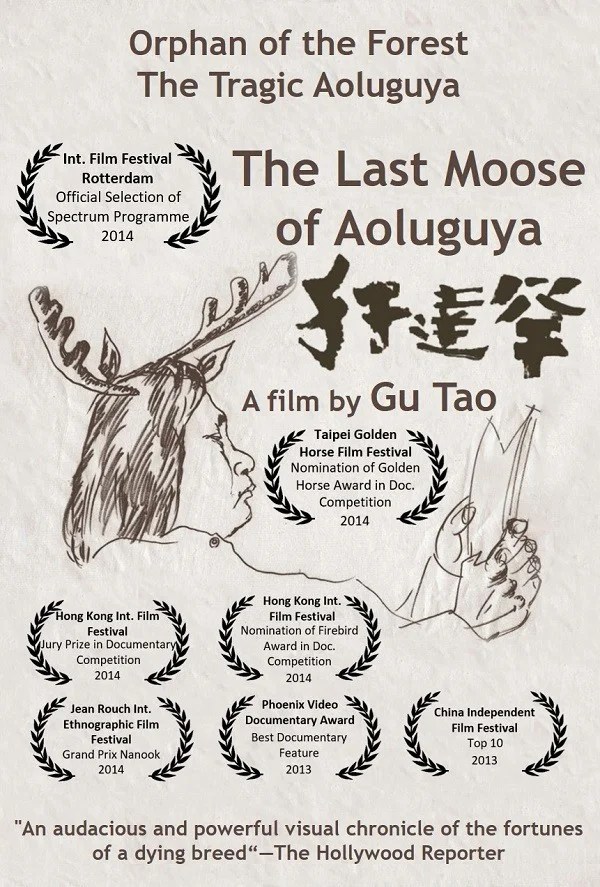

✿ Gu Tao (director), The Last Moose of Aoluguya 犴达罕, 2014. 99 min.

Since an internet influencer on Douyin recommended Chi Zijian’s novel The Right Bank of the Argun River (2005) in 2023, the Evenki people have entered the public imagination in mainland China in an unprecedented way.

In January 2024, multiple major news outlets reported that the Evenki tribe and their reindeer had “mysteriously” appeared on the famous Central Street in the northeastern city of Ha’erbin.1 Most recently, in the autumn of 2025, the Evenki resettlement habitat in Inner Mongolia was featured as a utopian backdrop for the marriage reality show See You Again (Season Five). In these popular representations, the Evenki, an originally nomadic hunter gatherer people, have been exoticised as a model minority in Northeast China, especially in contrast to the more “troublesome” Muslim communities in Xinjiang. In other words, by imagining the Evenki people in popular cultural venues as a good, pure, and peaceful ethnic minority 少数民族, who represent nature and the vast land of China, the state is able to justify national and colonial expansion across its many contested borderlands.2

Against this dominant socio-cultural background, I offer critical reviews of two cultural productions that represent the Evenki people, showing how they expose state violence of resettlement and assimilation carried out in the name of progress. As an ethnic group with one of the smallest populations, approximately 30,000 in China and 38,000 in Russia, the Evenki have lived in the Greater Khingan Range alongside the Mongol, Manchu, Oroqen, Daur, Han Chinese, Russian, and many other ethnic groups for centuries. Renowned for their reindeer herding practices, the Evenki are a nomadic people who have migrated along and across the Argun River, a major waterway that partially forms the border between present day China and Russia.

I will first reread Chi Zijian’s novel The Right Bank of the Argun River (2005), translated into English by Bruce Humes under the title The Last Quarter of the Moon. I will then introduce Gu Tao’s independent documentary film The Last Moose of Aoluguya (2013), originally titled 《犴达罕》, the Mandarin transliteration of “Kandahar,” the Mongolian name for moose. Notably, Chi is Han and Gu is ethnically Manchurian, and both have lived adjacent to Evenki communities in the Greater Khingan Range.3 Although neither work is a full self representation, they nevertheless provide crucial counter narratives. Chi’s and Gu’s representations of Evenki history and epistemology challenge the logic of national borders and industrial modernity.

The Last Quarter of the Moon

The Evenki lifestyle depicted in Chi’s novel confronts, rather than escapes, China’s postsocialist, neo capitalist modernity. Behind the predominantly exoticising reading of the novel, what I discern is a collective desire to identify state violence that is now experienced not only by nomadic ethnic minorities at the frontier but also by the everyday urban Chinese subject. Narrated by an unnamed ninety year old Evenki woman in a distinctive oral style, the novel opens with a statement that sounds counterintuitive to modern ears: “I won’t sleep in a room where I can’t see the stars. All my life I’ve passed the night in their company. If I see a pitch dark ceiling when I awake from my dreams, my eyes will go blind. My reindeer have committed no crime, and I don’t want to see them imprisoned either” (Chi and Humes, p. 4). The narrator’s grievance is directed at the resettlement project, namely the Forest Protection Project 天保工程 launched in the 2000s, which effectively displaced the hunter gatherer community from their centuries long living environment. The novel then turns to the elder’s memories, offering an account that moves from her childhood to the present narrative moment, interweaving stories of four generations that span more than a century.

A plot summary does not do justice to the literary and cultural value of the novel. Instead, I wish to foreground its representation of Evenki epistemology, that is, non exploitative and non human centric ways of living, thinking, and being. The novel documents major historical events in Evenki temporality, which stands as an alternative to Western or Han Chinese historical epochs. Calendar dates appear only as secondary references when describing imperial and civil wars, including China Russia, Sino Japanese, and CCP KMT conflicts, as well as the stages of communist and postsocialist China. By contrast, the narrative consistently foregrounds the reindeer, the forests, and the characters’ reciprocal relationships with other Evenki tribes and neighbouring ethnic groups, such as Russian merchants, Han Chinese farmer loggers, and Japanese military soldiers. Through fluctuations in collective well being, the novel reveals how characters formulate friendship and kinship in the face of conflict, violence, and betrayal within an Evenki epistemological framework. Numerous moments illustrate how humans may engage with the world, both spiritually and materially, in responsible ways. For instance, the practice of kolbo, storage hubs built throughout the forest and intended to serve mountain travellers in need of food and shelter during emergencies (Chi and Humes, p. 113), exemplifies a mode of material exchange grounded not in accumulation but in mutual obligation among strangers. Another example appears in the figure of Nihau the Shaman, who saves others’ lives at the cost of her own children because she refuses to distinguish between her children and those of others (Chi and Humes, p. 278). These material and cultural practices differ fundamentally from both capitalist modes of exchange and those of state organised communism.

The Last Moose of Aoluguya

If the political critique in Chi’s novel can be readily subsumed into the “dream of Han innocence,” as Kazakh scholar Guldana Salimjan argues, Gu Tao’s documentary faces a different but equally dangerous form of misinterpretation. The Last Moose of Aoluguya should not be read through the lens of victimhood. In some respects, Gu’s film can be understood as a sequel to Chi’s novel, as it follows an Evenki man, Wei Jia, in tracing the community and their lives after urban resettlement in the Aoluguya township. Living with Wei Jia for an extended period, the film crew follows him from the urbanised Aoluguya to the traditional settlement in the Greater Khingan Range, then to the southern city of Sanya on Hainan Island, and finally back to the mountains. Two interrelated themes run through this journey: Wei Jia’s life threatening struggle with alcoholism and his desire to hunt a moose in the traditional Evenki way.

Much like the unnamed narrator in Chi’s novel, Wei Jia’s resistance to urban resettlement does not suggest an inability to engage with modern change. On the contrary, he is able to defend his culture and his people against state violence through poetry and art, which function as expressions of both Evenki tradition and modernity. By challenging the moral and social stigma surrounding alcoholism, the film reveals a painful truth: Wei Jia is acutely self aware that drinking constitutes a compromised and self sabotaging response to the loss of Evenki hunting culture and to the intensifying pressure of assimilation into urban Han society. Crucially, alongside drinking, Wei Jia, his siblings, and other Evenki individuals of his generation, born in the 1980s, also turn to poetry and art as alternative means of articulating grievance and asserting agency. The moose, now on the brink of extinction due to massive logging during China’s socialist period, survives only in Wei Jia’s memory and in his oil paintings. These creative practices testify to his capacity to incorporate diverse artistic forms in the articulation of an Evenki identity.

This dynamic is perhaps most powerfully expressed in his poetry composed in Mandarin Chinese. Wei Jia’s poems, together with the poetic language captured on camera, resist both assimilation and the interpellation of the Evenki as “uncivilised” or “backward.” I conclude with two such poems, the same poems with which the film ends. The first is recited by a rivulet in the Greater Khingan Range following Wei Jia’s release from involuntary psychiatric hospitalisation in Sanya. The second is performed orally during a snowstorm, after Wei Jia reflects on the destructive effects of alcohol abuse among Evenki youth. Presented below in Chinese and in my English translation, the two poems demonstrate two sides of Wei Jia: love and anger. To understand his anger at state violence, non-Evenki audiences must first understand his love for his land and culture.

Poems

1

聆聽春日之靜

晴朗的天空傳來很熟悉的聲音

聲音與人之形構成立體

吟詠空間的詩

解釋著永恆的秘密

莊嚴地降落在湖面上

山坡上的棒雞正舉行著迎春儀式

大雁與棒雞相約的地方

化凍的冰河燦爛的運動之中

森林望著他已熟知的目光

凝視著聲音和色彩在遠方混合

聆听春日之静

Listen to the quietude of the spring

The bright skies carry familiar sounds

The sounds enveloping us

composing a poem of the forest

that interprets the sacred eternity

landing with solemnity on the lake

the pheasant on the hill conducting rites of spring

In their meeting place with the goose

the melting river glittering its movement

The forest gazing at its familiars

the sound and color melting together in the distance

2

现在社会进步了

狩猎文化消失了

工业文明带来了一个悲惨的世界

如果有更文明世界的警察向我开枪

那就

开枪吧

Society is progressing

Hunting culture is disappearing

The industrial civilization has turned the world into a miserable place

If the police of a more civilized world were to shoot at me

then I’d say

“Go ahead, shoot!”

- See Xinhuanet 新華網, The Paper 澎湃新聞, and QQ News QQ新聞. ↩︎

- Salimjan, Guldana. “The Dream of Han Innocence.” Los Angeles Review of Books, 27 July 2024. This piece critically examines the Chinese TV drama To the Wonder in terms of how it romanticises Xinjiang and masks colonial and extractive policies through an ideology of Han innocence. It offers relevant framing for tourism, cultural production, and frontier colonialism in Xinjiang.” ↩︎

- For reflections on their personal relationships with the Evenki as non community members, see Chi Zijian’s “Afterword: From the Mountains to the Sea,” included in The Right Bank of the Argun River and available in English translation on Bruce Humes’s blog, https://bruce-humes.com/2014/04/22/authors-afterword-last-quarter-of-the-moon/; and Gu Tao’s interview, “In the Midst of Life,” published by Made in China Journal in collaboration with the Australian Centre on China in the World, https://madeinchinajournal.com/2017/04/16/in-the-midst-of-life-an-interview-with-gu-tao/ ↩︎

How to cite: Liu, Yiwen. “Not Your Utopian Land: Rereading the Evenki Culture in Chi Zijian’s novel The Last Quarter of the Moon and Gu Tao’s documentary film The Last Moose of Aoluguya.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 22 Dec. 2025. chajournal.com/2025/12/22/last-quarter.

Holding a PhD in English from Simon Fraser University, Yiwen Liu is currently a SSHRC Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of Toronto. Her primary research focuses on Hong Kong Sinophone literature produced between the 1940s and 1980s, re-theorising the relationship between the Cold War and postcolonialism. She teaches theories and literatures of postcolonialism, diaspora, migration, and global Asias. [All contributions by Yiwen Liu.]