茶 FIRST IMPRESSIONS

茶 REVIEW OF BOOKS & FILMS

[REVIEW] “Realism and Memory in Chinese Film: Cecília Mello’s The Cinema of Jia Zhangke” by Tim Murphy

Click HERE to read all entries in Cha

on Jia Zhangke

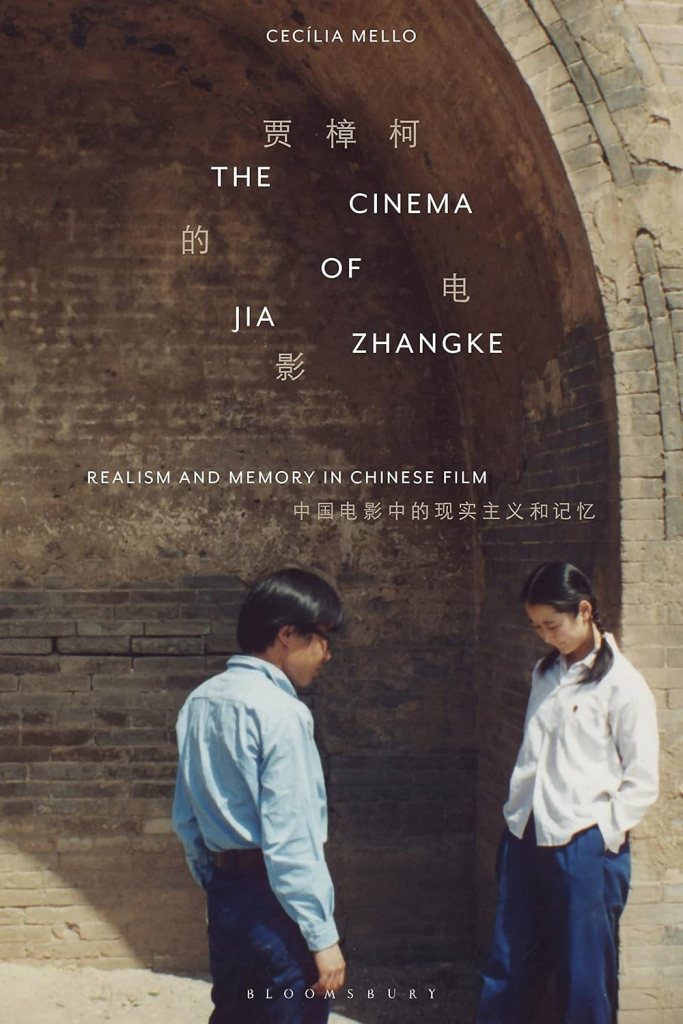

Cecília Mello. The Cinema of Jia Zhangke: Realism and Memory in Chinese Film, Bloomsbury Academic, 2019. 302 pgs.

The film director and auteur Jia Zhangke (pictured left) emerged in the 1990s as part of the so-called “sixth generation” of Chinese filmmakers, whose realist films portrayed the often negative consequences of internal migration and urbanisation during the globalisation of the Chinese economy. Born in 1970 in Shanxi province in northern China, Jia began making films as a student in Beijing. By 2019, when Brazilian academic Cecília Mello published this scholarly monograph, Jia had become “one of world cinema’s most original and important directors” (p. 1). The Cinema of Jia Zhangke: Realism and Memory in Chinese Film covers the director’s oeuvre of twenty-seven films at the time of publication, including features, shorts and documentaries. Mello’s in-depth analysis offers an impressive interpretation of Jia’s work grounded, first, in theories of cinematic realism and “intermediality” between artistic traditions, and second, in cinematic practices of remembering and representing memory. This specialist academic study is a significant addition to the English-language literature on Chinese cinema and is therefore essential reading for any student of world cinema. At the same time, although Mello’s analysis can at times be dense, the book’s thorough contextualisation also enables it to engage the interested general reader. It is, then, a book for Sinophiles as well as cinephiles.

Jia’s complex and distinctive cinematic style is rooted in a realist aesthetic. Cinematic realism, according to the influential French film theorist André Bazin (1918, 1958), seeks to articulate hitherto hidden or repressed facets of reality. Its modes of production include techniques such as deep focus and the long take, location shooting with natural light, and the use of semi- or non-professional actors. These characteristics are so prevalent in Jia’s work that Mello suggests he may fairly be described as “a Bazinian film-maker” (p. 4). Mello also emphasises the post-war Italian neorealist practices that Jia employs “to establish a direct approach with the real in all its materiality, ambiguity, contingency and mystery” (p. 3). In connection with this sense of directness, Jia was an early convert to digital technology, which, as the Brazilian director Walter Salles suggests in the Foreword to the book, “serves the urgency of his cinema” (p. xiii).

The Italian neorealist Michelangelo Antonioni was a major influence on Jia. Antonioni’s 1964 Red Desert, with its images of an angst-ridden Monica Vitti set against a background of industrial unrest in a petrochemical plant in northern Italy, has a particular resonance for Jia’s work. This is evident not least in Jia’s frequent casting of his long-time leading actress, and wife, Zhao Tao (pictured right), in scenes depicting the similarly unglamorous coal industry in Shanxi. Shanxi is by far China’s most important source of coal, with the province alone currently producing more coal than India. However, the fate of China’s coal industry, and thus the socio-economic future of the province, remains uncertain in light of environmental concerns surrounding fossil fuels. Jia’s films sometimes blend documentary and fictional modes, and while they occasionally portray characters who have prospered during China’s development, their primary focus is on those who are marginalised or alienated from the mainstream. The powerless individuals caught up in the maelstrom of rapid change in Jia’s films are often mobile figures such as city drifters (Pickpocket, 1997), travelling artists (Platform, 2000), migrant workers (The World, 2004; Dong, 2006; Still Life, 2006), and criminals (A Touch of Sin, 2013; Ash is Purest White, 2018).

In The Cinema of Jia Zhangke: Realism and Memory in Chinese Film, Mello argues that Jia’s aesthetic derives not only from cinematic realism but also from what Bazin regarded as cinema’s “impure” essence, namely the intrinsic intermediality or interrelationship between cinema and other art forms and traditions. “Intermediality” emerged as a critical term in the 1960s in the work of Dick Higgins and subsequently came to denote the heterogeneous interconnections between different media. Mello maintains that the distinctive style, narrative structure and character construction of Jia’s films depend on this Bazinian impurity or intermediality, that is, on the techniques and aesthetics of other Chinese artistic traditions, in order to convey meaning. She further suggests that Jia’s central thematic concern is the portrayal and examination of personal and collective memory within contemporary China. In a 2009 interview, Jia spoke of the way cinema “records memory, and how it becomes part of our historical experience” (cited on p. 24), and in Mello’s account his invocation of other art forms enables him “to interweave multiple temporal and meaningful layers that make room for the emergence of memory” (p. 9).

The chapter structure of the book is organised around “points of commonality relating to particular instances of an intermedial engagement with the real” (p. 24). The context of each chapter, in other words, is a distinct artistic tradition on which Jia draws in order to record and retrieve personal and collective Chinese memories. Chapters 2 and 3 examine the role of architecture in Pickpocket, The World, Still Life and Platform. Chapter 4 discusses the role of pop music in Platform, Still Life and Unknown Pleasures (2002). Chapter 5 explores landscape painting and philosophy in relation to Still Life. Chapter 6 considers Chinese operatic theatre, with particular reference to A Touch of Sin. Chapter 7 analyses the role of photography in Dong, Still Life, 24 City (2008) and I Wish I Knew (2010). Chapter 8 addresses spatial practice in Chinese garden architecture and its relationship to The World and Cry Me a River (2008).

Each chapter incorporates discussions of Chinese history and culture alongside an account of another artistic tradition, and Mello skilfully interweaves these elements into her analyses of specific films. Indeed, the book’s appeal beyond a specialist academic audience lies primarily in its contextualisation. A strong example is the discussion in chapter 5 of painting and philosophy in relation to Still Life, a film set amid the destruction and displacement caused by the Three Gorges Dam project on the Yangtze River in Hubei province. In Mello’s reading, the film shares aesthetic qualities with the Chinese tradition of landscape painting (shanshuihua 山水画) and with associated elements of Daoist and Confucian philosophy. Another example is her discussion of Chinese garden architecture in chapter 8. The chapter argues that while cinema mirrors gardens in its capacity to initiate “an emotional journey through multiple spaces”, ancient Chinese garden architecture constituted “a proto-cinematic experience on many levels” long before its Western counterpart. Prior to her analysis of spatial practice in Jia’s The World and Cry Me a River, Mello provides a broad overview of the “basic characteristics” of Chinese gardens from the Shang dynasty (1600 to 1046 BC) onwards.

Mello’s careful contextualisation is combined with persuasive arguments concerning the complex nature of Jia’s particular realist brand of cinematic “impurity”. Platform (2000), one of Jia’s most acclaimed early films, features prominently in Mello’s analysis of the interrelationship between cinema and architecture in chapter 3 and of the intermedial role of pop music in chapter 4. Platform is set in the 1980s, when the journey towards twenty-first-century globalisation was beginning in China, and the film artfully contrasts the post-Cultural Revolution world with what Mello describes as the “China of millennial traditions” (p. 9).

The film follows four friends who are members of a state performing troupe in Fenyang, Jia’s hometown in Shanxi, although parts of it were shot around the city walls of the nearby, historically preserved city of Pingyao. While noting that walls have been a defining feature of Han urban architecture since at least the Tang dynasty, Mello suggests that the fourteenth-century city walls of Pingyao “compose a type of metaphorical configuration that is integral to [Platform’s] style and narrative structure” (p. 61). In addition to several scenes in which the walls serve as the setting for a couple’s secret meetings (pictured on the book cover) and signify the obstruction of their relationship, which is strongly opposed by the woman’s authoritarian father, images of the troupe leaving the city to perform elsewhere have an upbeat quality, underscored by the receding view of the walls, whereas their returns are markedly more doleful. The walls evoke not only the past and the weight of history but also “the entrapment of a whole 1980s generation caught between reform and closure, opening up and enclosure” (p. 66).

Platform also includes several scenes in which characters listen to personalised pop music on cassette tapes or broadcasts from Hong Kong and Taiwan while reflecting on reports about the world beyond Shanxi. Mello observes that the immense popularity of songs such as Teresa Teng’s “Mei jiu jia kafei 美酒加咖啡” (below) stemmed from their innovative use of first-person enunciation, in which the personal pronoun “I” replaced “We”. She argues that Jia deploys pop music in Platform “as a historical, memorial, narrative and aesthetic tool, able to create different journeys and passages across geographies, moving between the individual and the collective, and within oneself” (p. 90). For Mello, the pop songs that punctuate Platform, as well as other films such as Still Life and Unknown Pleasures, are fragments of Jia’s personal memory transformed into collective memory through cinema, while their intimate dimensions serve to signify the early emergence of modern individualism in China during the 1980s.

Mello’s monograph concludes with an afterword, chapter 9, devoted to I Wish I Knew (2010), a documentary film commissioned for the Shanghai World Expo in 2010 but containing no direct reference to the event itself. Instead, the film focuses on the ways in which personal stories are interwoven with the history of Shanghai, presenting eighteen interviews with current and former residents of the city. Michelangelo Antonioni’s 1972 film about China, Chung Kuo, appears in I Wish I Knew through an interview with Zhu Qiansheng, one of the Shanghai crew members on that production. In Taiwan, Jia also meets another of his key directorial influences, Hou Hsiao-hsien, who relocated as an infant from Guangdong province to Taiwan with his family in 1948.

Mello observes that in Hou Hsiao-hsien’s appearance in I Wish I Knew “there is an underlying sense of loss, a feeling of rootlessness, of never quite belonging, typical of those who were exiled from their country of birth” (p. 229). Jia’s engagement with the theme of migratory displacement continues in his 2024 film Caught by the Tides, which, owing to restrictions on filmmaking introduced during the COVID pandemic, is his only film to date since the publication of Mello’s book. Caught by the Tides presents a panorama of twenty-first-century social change in China, drawing on footage from several of Jia’s earlier films alongside documentary material he himself recorded over the years. Its familiar style, together with its pronounced intertextuality and intermediality, renders the film a kind of summation of Jia’s filmmaking career thus far.

While Jia’s realism has depicted many of the adverse consequences of China’s developmental trajectory, it would be misleading to characterise him as a critic of the Chinese state or ruling party. Like many “sixth generation” filmmakers, Jia’s films have frequently been censored in China despite their success at international film festivals and arthouse venues, yet his cinema is not regarded as subversive in a confrontational sense. He has remained resident in his native country and in 2017 was a co-founder of the Pingyao “Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon” International Film Festival, established to champion emerging Chinese filmmakers. Mello addresses Jia’s public roles in China, including criticisms of his participation in advertising campaigns as alleged “betrayals” of the neorealist spirit, by arguing instead that his art “does not sit well with notions of purity, simplicity and ideologies. It is impure, complex and contradictory, and this is where its great wealth lies” (p. 148). Views may differ regarding the responsibilities of artists, but what is beyond dispute is that The Cinema of Jia Zhangke: Realism and Memory in Chinese Film is a major work of film theory devoted to an important and influential director. Specialists will be stimulated by the originality and depth of Mello’s scholarship, while engaged general readers will gain a strong sense of how Jia Zhangke both draws upon and generates memory, or, as Walter Salles observes in the Foreword, how he “unveils” memories through multifarious strands of Chinese history, culture and art.

How to cite: Murphy, Tim. “Realism and Memory in Chinese Film: Cecília Mello’s The Cinema of Jia Zhangke.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 15 Dec. 2025, chajournal.com/2025/12/15/jia-zhangke.

Tim Murphy is the author of two poetry collections, Mouth of Shadows (SurVision Books, 2022) andUpward Spiral (Red Moon Press, 2025). His poetry has appeared in journals including Abridged, Anthropocene, Eratio, Maintenant, The Honest Ulsterman and NOON: a journal of the short poem. He previously worked as a philosopher of law at universities in the UK, France, Ireland, Iceland, Malaysia and Spain. His academic publications include Rethinking the War on Drugs in Ireland (Cork University Press, 1996) and Law and Justice in Community (with Garrett Barden; Oxford University Press, 2010). Originally from Cork in Ireland, he lives in Spain. [All contributions by Tim Murphy.]