茶 FIRST IMPRESSIONS

茶 REVIEW OF BOOKS & FILMS

[ESSAY] “The Burden of Representation: Pillion and the BDSM Representation on Screen” by Hongwei Bao

Click HERE to read all entries in Cha on Pillion & Box Hill.

Editor’s note: Hongwei Bao revisits the conversations prompted by Pillion’s UK cinema release, following both his earlier Cha review essay of the film and his writing on Adam Mars-Jones’s Box Hill (2020), the novel on which the film is based. His new piece reflects on how Pillion extends the book’s themes while responding to current debates about BDSM representation and queer storytelling.

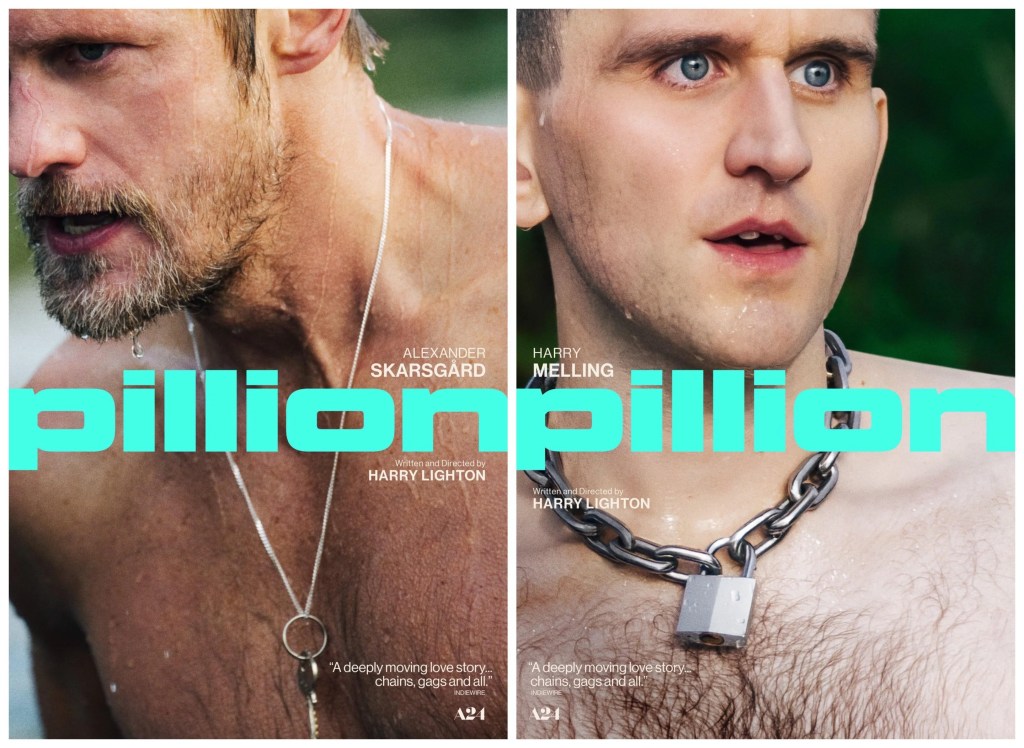

Harry Lighton (director), Pillion, 2025. 103 min.

Since its premiere at the 2025 Cannes Film Festival in May 2025, Harry Lighton’s directorial debut Pillion has received international recognition, including Best Independent Film, Best Debut Screenwriter, Best Costume Design and Best Make-up and Hair Design at the British Independent Film Awards, which attests to its artistic merits. As of 3 December 2025, the film holds a rating of 7.4 out of 10 on IMDb and a 100 percent approval score on Rotten Tomatoes. Peter Bradshaw, reviewing for The Guardian, compares the film to “a cross between Alan Bennett and Tom of Finland with perhaps a tiny smidgen of what could be called a BDSM Wallace and Gromit. It’s basically what Fifty Shades of Grey should have been.” There are, however, dissenting views, and writing for Queer Guru, Justin David offers a critical assessment of the film’s portrayal of kink: “What I saw here felt cold and disconnected. I genuinely couldn’t see what either character gained. Not on the surface, anyway.”

Just as BDSM is not everyone’s cup of tea, and as a non-normative sexual and subcultural practice it is unlikely to be, Pillion does not have to appeal to every member of the audience. The film is rated 18 and above by the BBFC, which means it is not family friendly, and its graphic depiction of sex and nudity may outrage sexual and religious conservatives. That the film exists at all, and is made and released in cinemas in 2025, is perhaps one of its most significant achievements, testifying to the artistic freedom of the film industry, which is increasingly curtailed by political and commercial pressures, as well as to the broad acceptance of LGBTQIA+ people in many societies.

In my review of the film for Cha, I place it within the history of queer cinema, emphasising that it marks an important milestone in the visual representation of BDSM culture. Pillion belongs to a genealogy of films that depict bikers, including The Wild One (dir. László Benedek, 1953), Scorpio Rising (dir. Kenneth Anger, 1963) and Rebel Dykes (dir. Siân A. Williams and Harri Shanahan). These films share a bold, unapologetic celebration of leathersexuality and the spirit of rebellion. Leather-clad “kinky gay bikers” have become a powerful visual emblem of sexual and social nonconformity, challenging both heteronormative and homonormative values. Pillion is best understood within this radical lineage of queer representation. Queer cinema is not intended to offer the audience pleasing images of gay life but to pose difficult questions about the complexities of sexuality, desire and social conventions.

Compared with the controversial film Cruising (dir. William Friedkin, 1980), a crime thriller that depicts New York’s underground leather subculture in the 1970s, Pillion offers a less sensational, voyeuristic and exploitative representation of the gay leather community. In contrast with the more recent Fifty Shades of Grey (dir. Sam Taylor-Johnson, 2015), an erotic romantic drama that introduces BDSM to a mainstream audience, Pillion places stronger emphasis on BDSM as a subcultural and social practice. Beyond its intimate scenes, the film shows gay bikers, performed by real members of the GBMCC, gathering at private parties and in outdoor spaces, engaging in unconventional sexual practices and forming a subcultural community. These bikers and other members of the leather, kink and BDSM communities have also taken an active role in various screening events. Pillion therefore represents a more ethical mode of filmmaking in which the filmmakers work closely with the communities portrayed, ensuring their voices are heard while avoiding stereotypes and misrepresentation.

Films representing historically marginalised communities are often confronted with the “burden of representation”, a term Kobena Mercer uses to describe the heightened expectations placed upon films that depict the Black experience. Because of historical injuries and the lack of visibility, films that portray marginalised communities are frequently expected to provide perfect representations, as if such depictions could repair long-standing social and historical injustices. Since films representing BDSM and kink experiences remain rare, both LGBTQIA+ audiences and the general public may load more expectations onto Pillion than usual. When do we expect heterosexual films to represent perfect, harmonious families, or crime thrillers to portray an orderly society? Members of LGBTQIA+ communities may wonder whether the film reflects their personal experiences, or whether it offers a positive portrayal of the community. General audiences may question whether the film is suitable for all ages, including children and the elderly, which it is not, hence its 18 rating. They may ask whether the film mirrors the LGBTQIA+ individuals they know, which is unlikely, since no single film can encompass the breadth of any community. The desire to map the narrative of a film onto the experience of a community, a society or an individual is, inevitably, destined to fall short.

Perhaps we should view Pillion as it is, a story about a specific BDSM relationship between Colin and Ray. Their dynamic is singular and unconventional, and it may not resemble other relationships, yet this does not make it more or less valid. Colin and Ray’s relationship is like no other, even within kink, leather and BDSM communities. What matters is that the film avoids easy conclusions and moral judgements. It does not declare their relationship good or bad, healthy or unhealthy, abusive or not. It tells the story and invites the audience to form their own interpretations. “Showing, not telling” remains a sound principle for successful storytelling. Pillion does not attempt to represent a monolithic community experience, either. It presents a complex narrative that prompts reflection and discussion, and in this respect the film achieves what art can at its best.

For people who have suffered abusive relationships or traumatic experiences, however, Pillion may not be the most suitable viewing, and they should, if possible, avoid it. Yet it is crucial to distinguish between a consensual BDSM relationship and an abusive one. BDSM is always grounded in “safe, sane and consensual”; any breach of that principle becomes abuse. Pillion reveals how delicate that boundary can be, and how intricate human emotions and desires often are.

As David Rooney writes in his review for The Hollywood Reporter, “Pillion is less about the shock factor of some very graphic gay kink than the nuances of love, desire and mutual needs within a sub/dom relationship.” Here, “nuances” does not refer to a simple division into black and white; it speaks to the fifty shades, or five thousand shades, of human desires, emotions and experiences. As John Bleasdale observes in his review for Sight and Sound, “Some relationships are meant to last forever; others might be passing. That doesn’t make them any less valid. What the film assures us of is that this is transformative for Colin and perhaps Ray too.” We might also see Pillion as a transformative film in terms of BDSM representation. It is concerned with what people enjoy or do not enjoy in their own sexual lives, with openness, and with learning to consider BDSM in different ways through the perspectives of Colin and Ray, regardless of how much we may disagree with them.

How to cite: Bao, Hongwei. “Representing Radical Queer Love on Screen: Harry Lighton’s Pillion.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 4 Dec. 2025, chajournal.com/2025/12/04/representation-pillion.

Hongwei Bao is a queer Chinese writer, translator and academic based in Nottingham, UK. He is the author of Queer China: Lesbian and Gay Literature and Visual Culture under Postsocialism (Routledge, 2020) and Queering the Asian Diaspora (Sage, 2025) and co-editor of Queer Literature in the Sinosphere (Bloomsbury, 2024). His poetry books include The Passion of the Rabbit God (Valley Press, 2024) and Dream of the Orchid Pavilion (Big White Shed, 2024). [All contributions by Hongwei Bao.]