[EXCLUSIVE] “Seeing the Unseen: Lessons from Tai Po” by Stuart Lau Wai-shing, translated by Tammy Lai-Ming Ho

“What is essential is invisible to the eye.”

Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, The Little Prince (1943). Spoken by the fox during his lesson to the Little Prince.“All that is solid melts into air.”

Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, The Communist Manifesto (1848), Chapter One, “Bourgeois and Proletarians”.

O

Roland Barthes writes in Camera Lucida that the truest meaning of a photograph does not reside in what is offered openly to sight. The deepest moment lies elsewhere, beyond the visible particulars, in that private and affective spark which no gaze can wholly contain. When he contemplates a photograph, he is drawn towards the eyes within it. Looking upon the portrait of Napoleon’s younger brother, he speaks of its punctum as lying in those eyes which once beheld Napoleon and watched the whirlwinds that remade Europe. These past days, I, who have lived in Tai Po for so long, have found his words returning unbidden.

When I saw, beyond the police cordon, the platform where survivors of the Wang Fuk Court fire had gathered, I watched them staring at their own homes as they burned. Some cried out that they had lost contact with their families. Some covered their eyes, unable to bear the sight, yet still peered anxiously through their fingers, tears blotting the gaps between them. In those eyes one saw not only sorrow but desolation, anger, and self-reproach. These emotions weigh heavily for the people of Tai Po, and empathy renders them piercingly clear. Yet have any officials perceived them? Are they reduced to nothing but “mouths”, given only to sophistry and evasion?1 They have eyes, but do they have vision? Have you all seen what’s happening?

If even these helpless, grief-stricken gazes have gone unseen, then all that lies outside the frame stands no chance at all. Consider the volunteers who had come of their own accord, busy sorting supplies. As they bent to their work they would lift their heads and cast sideways glances towards the line of Care Team members in their bright vests, posing for photographs.2 None of those sidelong looks, none of that cool disdain, will appear in the images. Those cheerful snapshots will likely grace some future report written to flatter tranquillity, though how many will notice, behind the staged smiles, the civilian-donated goods silently revealing that beyond the frame many eyes were watching askance.

During my run this morning I saw police driving away the volunteers and the Care Teams taking full control of the collected goods, treating those who had hurried to aid the victims as though they were thieves. The absurdity of it left me dazed, as if I had strayed into another land. Have you seen all this?

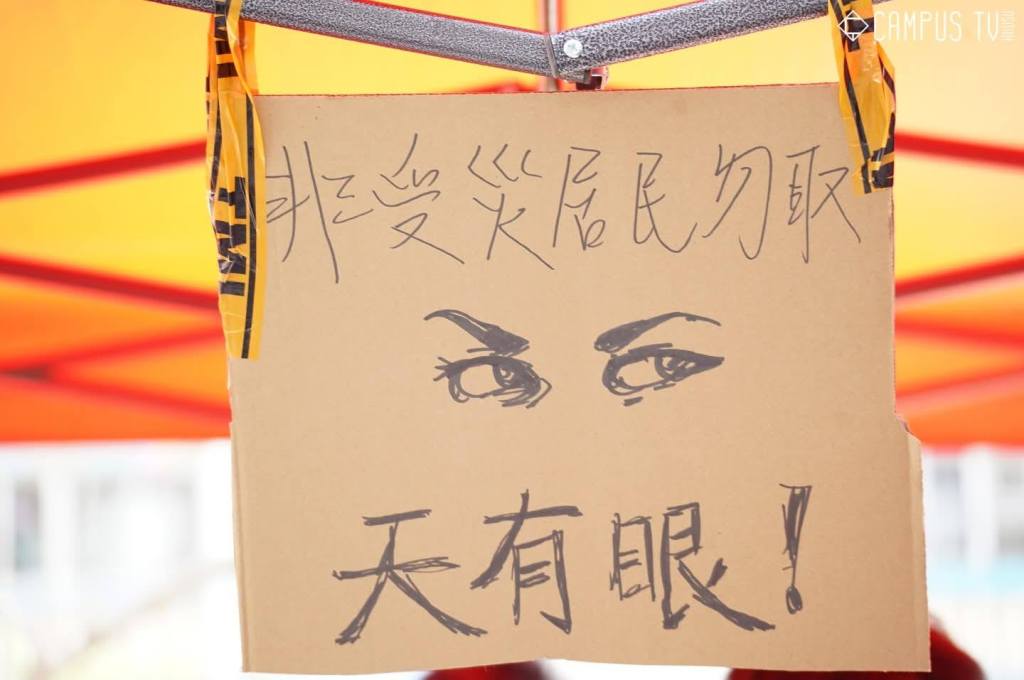

There is another pair of eyes, the sort once printed on the old posters of my childhood which warned that litterers would be despised by all. (「亂拋垃圾,人見人憎」, Fig. 1) Now these eyes have been drawn hastily on a scrap of corrugated cardboard, above the words: “Residents not affected by the disaster must not take these. Heaven has eyes.” (「非受災居民勿取!天有眼!」, Fig. 2) Though sketched quickly by a student, they carry indignation and the resolve to uphold justice. This sense of justice is that spark of goodness and righteous spirit which grows naturally from a conscience formed on the teachings of Confucius and Mencius. No reform of curriculum, no examination crafted to bypass thought and usher students straight to predetermined answers, can wholly extinguish it.

Fig. 1

Fig. 2

In recent years we have laboured, in an anti-intellectual spirit, gone to great lengths to empty the term “critical thinking” of its force, dressing it up instead as mere “clarified reasoning”, in the hope that students would thereby be “purified” and “dulled”. Yet before matters of true moral weight, are not these Heaven-seeing eyes the most immediate expression of the very clarified reasoning we claim to prize? Have you not heard the sharpness of their rebuke? Perhaps the expensive “Heaven’s Eyes” surveillance we have installed can only recognise faces and cannot discern the essential meaning held within a human gaze. Which side, then, is in genuine need of learning how to reason clearly.

After disaster strikes, one perceives most clearly the civic character of a place. I recalled a recent news report: in a country we have been fiercely criticising of late, a powerful earthquake had struck, shopfronts stood wide open, yet without any surveillance not a single victim took goods without permission, and at the points where relief supplies were distributed the young yielded their places to the elderly. And we, who speak so proudly of critical thinking, see it used here to justify open calls for the beheading of another nation’s leaders. When I saw that cardboard sign with its Heaven-seeing eyes, tears rose unbidden, and I remembered the line often attributed to Rousseau: “I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it.”3 The difference here is that I stand in wholehearted agreement with the students, and as an educator I would defend to the death the clarified reasoning that moved them to draw those eyes; for if teachers are commanded to suppress such eyes, what remains of our city? Have you seen all this?

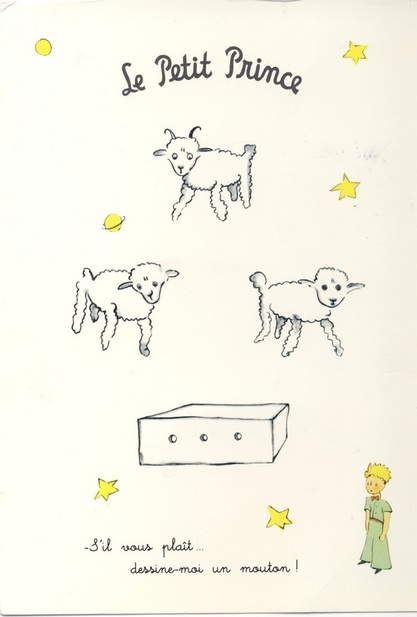

The truly important things are invisible to the eye. In The Little Prince a similar truth appears. The Little Prince asks the aviator to draw him a sheep. Several attempts fail to satisfy him. At last the aviator draws a box with a small opening, and the Little Prince is overjoyed. We all know this scene. I had feared that students had become like the trembling sheep the aviator first drew, as fragile as Dolly the cloned ewe. Yet what I saw instead was that the students drew me a box, and on one of its sides they cut three small openings. Peer inside and one sees the words Heaven, Has, Eyes.

“… suddenly a little boy comes from nowhere and asks him to draw a sheep”

Running once more along the Lam Tsuen River this morning, I saw again the building burned through. A tight ache seized my eyes as though someone had fastened a rubber band around them. I did not photograph the ruins again. I took instead a picture of Tolo Harbour, lying before the building, and silently wished all my neighbours in Tai Po a peaceful way forward. I believe that far off on the horizon the hinges of Heaven’s justice continue to turn, quietly, like a deep ocean current that moves slowly but moves all the same. I trust you can see that it still flows in silence, and that you have now become part of the force that urges it onward.

Tolo Harbour

“All that is solid melts into air” is the title of a work by Marshall Berman, whose subtitle is The Experience of Modernity. I believe that along the path of modernisation there remain certain values sacred as relics which we must guard from dissolution. I do not know precisely how one guards them. I know only that to look with one’s whole heart for what the eye cannot see is an essential part of the task.

Saturday 29 November 2025.

- Translator’s note: In Chinese, the author makes a visual pun on the structure of the character 「官」 (guan), meaning official. The small square component 「口」 means mouth, and in early or stylised forms the lower part of 「官」 was written with two stacked 「口」 components, creating the image of an “official” made of two mouths. This visual arrangement is often used to suggest someone who speaks much but sees little, or whose authority rests on words rather than genuine insight. Although modern forms of 「官」 no longer show the two mouths clearly, the traditional association remains and underlies the critique. ↩︎

- Translator’s note: Following the Wang Fuk Court fire in Tai Po in November 2025, District Services and Community Care Teams were deployed as part of the community-level response, assisting alongside government departments and volunteers in providing support to affected residents. Their involvement was reported in local media coverage of the relief efforts. At the same time, Care Teams have been the subject of public criticism in Hong Kong, with commentators noting concerns about political alignment, the potential use of community service for image-building, and public scepticism toward the visibility of Care Team members during emergency operations. ↩︎

- Translator’s note: The quotation is not by Rousseau or Voltaire; it was written in 1906 by Evelyn Beatrice Hall as a summary of Voltaire’s views in The Friends of Voltaire. ↩︎

How to cite: Ho, Tammy Lai-Ming and Stuart Lau Wai-shing. “Seeing the Unseen: Lessons from Tai Po.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 2 Dec. 2025, chajournal.com/2025/12/02/taipo.

Born and raised in Hong Kong, Stuart Lau Wai-shing received his PhD from the Department of Humanities and Creative Writing at Hong Kong Baptist University. He is a publishing professional and a part-time university lecturer in writing, editing and publishing. Lau is the author of several prose collections, including Alpine Forgetting of Shadow (2021), Obtuse Angle of Wings (2012) and The Child Holding a Flower (2007), as well as recent poetry collections Window, Pool, Unrippled (2024), Modest Heat in Fruits (2020) and How Broad Are the Plank Roads of Sunshine (2014). In 2021, he was awarded “Artist of the Year (Literary Arts)” by the Hong Kong Arts Development Council.

Tammy Lai-Ming Ho is the author of If I Do Not Reply (Shearsman Books, 2024), the editor-in-chief of Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, a founding co-editor of Hong Kong Studies, the English editor of Voice & Verse Poetry Magazine, and the translation editor of The Shanghai Literary Review. Formerly a tenured Associate Professor at Hong Kong Baptist University, she is an Honorary Researcher at the Richard Charles Lee Canada-Hong Kong Library at the University of Toronto and a Cheney Creative Fellow at the University of Leeds. She currently lives in Europe. Visit her website for more information.