茶 FIRST IMPRESSIONS

茶 REVIEW OF BOOKS & FILMS

[FIRST IMPRESSIONS] “Where Do We Belong? On Language, Migration, & Teresa Wong’s All Our Ordinary Stories” by Rebekah Chan

Teresa Wong, All Our Ordinary Stories, Arsenal Pulp Press, 2024. 240 pgs.

I found the graphic novel All Our Ordinary Stories by Teresa Wong while searching for a sense of self. Having left Hong Kong almost four years ago, I felt out of place when I returned to Canada.

In Hong Kong, I was regarded as more Western, but in Canada I felt far more Chinese than my other Canadian-born Chinese counterparts. I therefore turned to literature in the hope of finding myself, reading the works of other Chinese women from North America and Hong Kong in desperation to situate myself somewhere in between. This was how I discovered Wong’s multigenerational family odyssey recounting how her family came to live in Canada from China and Hong Kong.

Before the story even begins, there is a disclaimer. Wong writes:

Notes On Language

My first language—the language of my family—is Cantonese. And even though I don’t speak it well, you can assume all conversations I have with my parents and other Chinese elders in this book occur in Cantonese. I have chosen to keep some Cantonese words untranslated because I feel they are better represented and more meaningful in their original form… I also use Mandarin Pinyin for many Chinese place names to make them easier to locate on a map. If you find this jumble of language and dialects frustrating, please know that it is even worse inside my head.

This patchwork of languages, a key characteristic of the diaspora, arises when immigrants and their children adapt and assimilate while maintaining knowledge of their heritage language. The result is a hybrid of English shaped by Chinese grammar, or Chinese words scattered within sentences in which they would not normally appear. Yet this is precisely where they do belong, where they fought to belong. Wong’s story of her broken Cantonese is itself a story of migration, of a language that has survived outside its origin and natural environment.

For example, on page 120, Wong remarks within the sky of a hilly countryside drawing: “For the longest time, when I asked my mom where she was born, she’d simply say, ‘heung haa,’ which I mistook for a place name.” The term “heung haa” is not fully realised until one sets foot in one’s ancestral village. That is exactly where Wong goes, seeking greater clarity about her family’s history.

The story has multiple beginnings because she is searching for a starting point. The first beginning opens with a hospital scene, where her mother is recovering from a stroke and subsequently falls into a depression. In this moment, Wong is unable to communicate affection or comprehend her mother’s suffering. She cannot help but wonder about the hardships her mother endured.

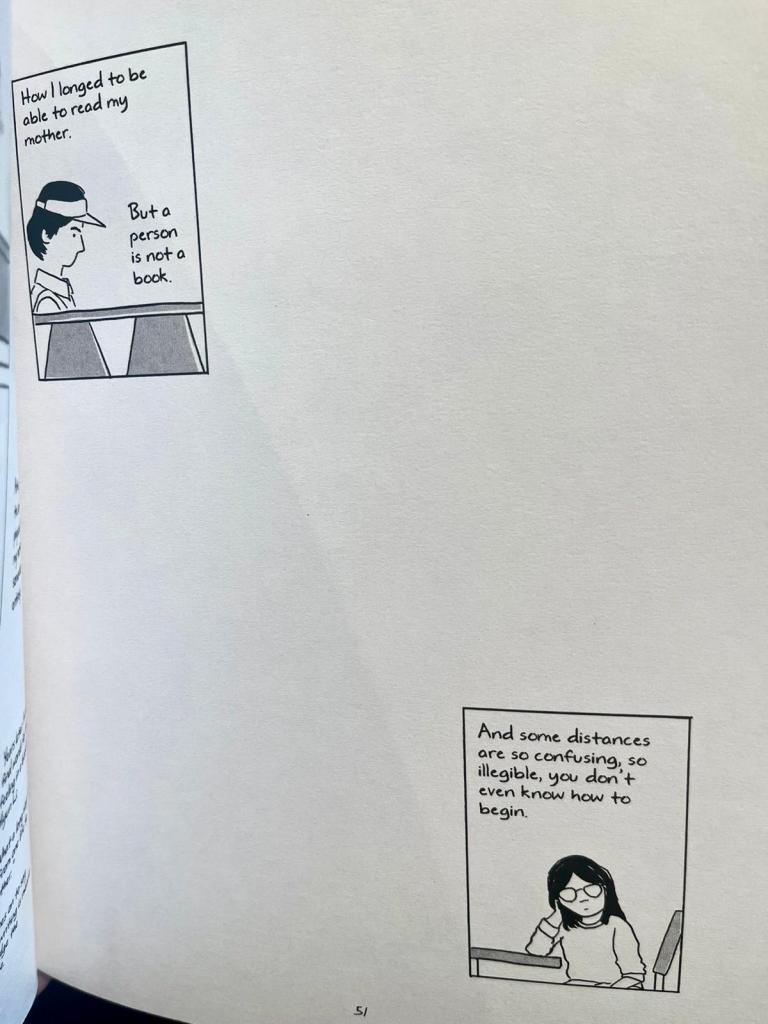

Wong longs to understand her parents and their seemingly dismissive behaviour. Through calm prose and minimalist panels, she searches for meaning within the greater historical events that shaped the generations before her, such as Canada’s Chinese Exclusion Act, the Cultural Revolution and the Great Leap Forward.

In what is perhaps the most moving of the stories she pieces together, we witness her mother’s escape from a commune in 1969 in Guangzhou, China, and her swim to Hong Kong. Even within my own family, there are stories of friends and relatives who swam to Hong Kong from China. Yet I never knew, or perhaps never searched as diligently as Wong did, the exact logistics or route. Contrary to her mother’s assertion that “It’s such an ordinary story,” I had no idea how extraordinary it truly was.

Wong also explores her Chinese-ness, or her perceived distance from her heritage, which deepens the emotional divide between herself and her mother. Her use of blank space and wordless panels heightens this vastness even further. Wong often highlights her lack of Chinese proficiency as a central reason she and her mother struggle to understand one another, adding to the difficulty of uncovering the answers she most seeks: “Where did I come from?” “Where are we going?”

Like Wong, I was troubled by the same questions. I too wished to know how my family’s origins might inform my future direction.

For as long as I can remember, I understood the term “heung haa” to mean “ancestral village of origin.” Yet when I asked my mother about the Chinese characters, she explained that it was merely a colloquial expression, not something used in formal writing. Although the word can be written in Chinese (鄉下), or in Wong’s transliteration “heung haa,” it is used primarily in vernacular Cantonese, a language that loses relevance with each passing day.

Wong has meticulously learned and recorded her family’s origin story, her own “heung haa,” preserving what might otherwise have been forgotten or left unheard forever. Perhaps we too may recognise the urgency of transcribing and safeguarding our own shared stories and languages, just as she has done.

How to cite: Chan, Rebekah. “Where Do We Belong? On Language, Migration, and Teresa Wong’s All Our Ordinary Stories.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 23 Nov. 2025, chajournal.com/2025/11/23/ordinary.

Rebekah Chan is from Toronto and has also lived in Singapore, Tokyo, and Hong Kong, where she completed her MFA at City University in Hong Kong. While in Hong Kong she served as Editor-in-Chief for her MFA legacy anthology, Afterness: Literature from the News Transnational Asia, and held the position of Community Manager for the Hong Kong Writers Circle. In Japan she wrote for the lifestyle magazine Tokyo Weekender. Her literary work appears, or is forthcoming, in Tupelo Quarterly, Blood Orange Review, Wild Roof Journal, Reed Magazine, and more. Rebekah is currently based in Toronto and writes about loss and belonging. Her writing is also supported by the Canada Council for the Arts. You can find her at @bx_writenow on Instagram.