茶 FIRST IMPRESSIONS

茶 REVIEW OF BOOKS & FILMS

Editor’s note: Ai-Ting Chung’s essay “Toxic Humidifiers and Atmospheric Thinking in Air Murder” examines Air Murder (2022), directed by Jo Yong-sun, as an ecocinema work grounded in real-life tragedy: South Korea’s humidifier disinfectant disaster, which killed and injured thousands between the 1990s and 2011. It argues that the film’s portrayal of domestic intimacy, corporate corruption, and state indifference transforms air itself into a metaphor for atmospheric injustice.

[ESSAY] “Toxic Humidifiers and Atmospheric Thinking in Air Murder” by Ai-Ting Chung

Jo Yong-sun (director), Air Murder, 2022. 118 min.

On 22 April 2022, Earth Day, the film Air Murder (2022) was released, bringing renewed attention to the humidifier disinfectant disaster in South Korea. Two weeks earlier, the Environmental Health Citizens’ Center held a press conference at Gwanghwamun, Seoul. The speakers revisited nearly three decades of suffering and criticised the companies Oxy and Aekyung, which had ignored both the dead and the many survivors still seeking justice. The conference ended with a call for public participation, urging citizens to watch Air Murder and join a boycott of the corporations that had produced and sold the disinfectant so carelessly.

This essay looks at the shared atmosphere surrounding this air-borne disaster and considers how air itself shapes public feeling and public harm. By understanding the disaster as a form of atmospheric pollution, I suggest shifting our attention from air as a neutral material to the wider pursuit of “good” air and the stark inequalities that pursuit reveals in a highly capitalised Korean society. Instead of presenting a documentary, Air Murder depicts the disaster through intimate and emotional spaces, from family life at home to the charged crowds gathered at the courthouse. Through these scenes, the film brings into focus the social and political injustices that allowed the tragedy to unfold. I describe the transformation of air into a metaphor that invites public awareness and empathy as atmospheric thinking.

To think about atmospheres is to consider how air shapes our emotions and our lives. It helps us reflect on the tension between the air we breathe, the rapid pace of economic growth, and our desire for comfort and modernity. Atmospheric thinking allows us to see how air inequality is produced and justified, and how it reflects uneven power within the nation. In his book Air Conditioning (9), Hsu L. Hsuan asks how “air quality and ambient temperature affect people’s moods, relationships, and work experiences?” I extend this further: how does the pursuit of air quality itself reshape society? How does it support the humidifier industry and influence the choices consumers make? As Hsu observes, air conditioning is something that middle-class people “were long encouraged to take for granted” (3), and the same is true of air quality. Humidifiers have become a staple of middle-class homes, presented as essential for a comfortable winter. I argue that consumers are not only encouraged to buy a product but are steered towards a particular vision of middle-class life through their pursuit of clean and pleasant air.

Based on the 2016 novel Fungus: Humidifier Disinfectant and the Unspoken by So Jae-won, the social activist and novelist known for the film adaptation Air Murder (2022), also released internationally under the title Toxic, had completed preparations for the film even before the novel’s release. As mentioned, the story of Air Murder explores the nationwide investigation into humidifier disinfectant lung injury in South Korea between 1994 and 2011, revealing the social injustice behind the 2011 statistical report published by the Korea Centers for Disease Control. More than one hundred people, including infants and pregnant women, died simply because they used humidifier disinfectants purchased at local marts. Rather than centring the victims, the film exposes the corruption at the heart of Korean capitalism, revealing corporations concerned only with their own interests and politicians who exploit tragedy to consolidate power. These forces together created the conditions for incomprehensible deaths for which no one has been held accountable. In this essay, I consider how we might make meaning of such collective trauma by broadening our understanding of ecocinema. If ecocinema offers a way to speak about environmental crises, such as the humidifier disinfectant disaster, how can we articulate what remains unspoken, as the title of the novel suggests? How do cinematic narrative and the broader mediascape shape or fail to shape atmospheric thinking?

To illustrate how atmospheric thinking appears in a mediascape, I discuss several scenes from the film and examine the emotions that arise within them. By tracing these emotional textures, I aim to show how the film invites its audience to interpret it and how I have come to read it myself in the hope of expanding the conversation around ecocinema.

The opening sequence presents a familiar middle-class household: a husband asleep on the couch and being reproached by his wife the following morning. She stands in the kitchen preparing breakfast, aware that he has come home late after a night shift and too many drinks with colleagues. On the living-room wall, the camera pauses on a family photograph. The setting, the dialogue, and the gestures between the characters create the impression of a comfortable nuclear family. The father, dressed for work, leans over his son’s bed and says, “Don’t be sick, it hurts me, too,” a line that underscores the warmth shared among them. This simple morning routine establishes the protagonist, Jung Tae-Hun, within his stable world: a well-off family sustained by a diligent husband and a caring wife. Their main worry is the health of their young son.

The film then presents Jung’s professional world through a scene in which a colleague laments the intense pressures faced by doctors in Korea. This conversation leads to the introduction of a new character, Han Young-Ju, the sister of Jung’s wife, who is a contentious prosecutor associated with a violent incident in which she assaulted a sexual predator after leaving the courtroom. The emotional tenor of the scene contrasts the anxious, troubled expressions of onlookers with the quiet pride that Han displays.

These two figures embody expertise in distinct yet equally significant spheres: the medical and legal systems. Without their professional knowledge and their resolve to pursue the humidifier disinfectant case, exposing corporate wrongdoing and challenging both the companies and the government would have been impossible.

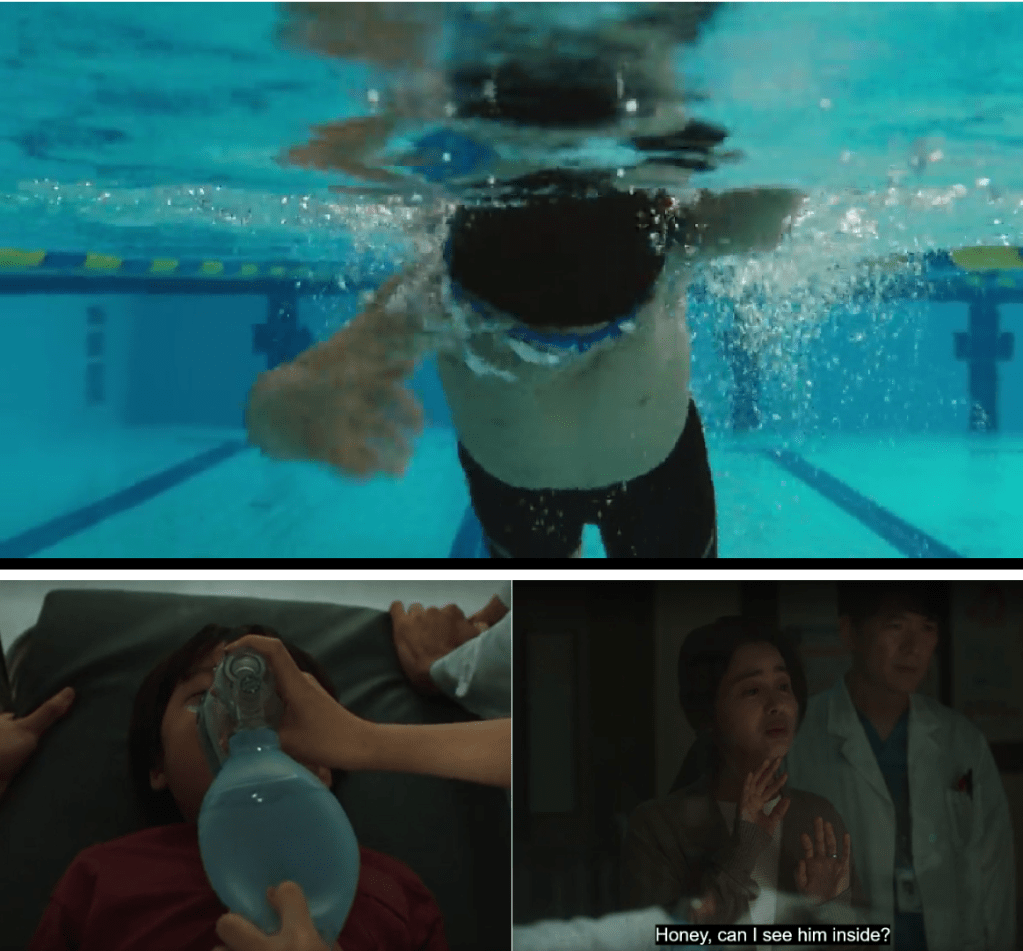

To represent the unrepresentable nature of air, the camera depicts Jung’s son swimming and slowly drowning in a pool. This visual motif echoes both the film’s title, “Air Murder,” and the later image of the boy relying on an oxygen mask in hospital. Unexpectedly, after the son is admitted, the narrative cuts to Jung attending his wife’s funeral. Both his wife and son were diagnosed with pulmonary fibrosis, a condition in which lung tissue becomes scarred and thickened, making breathing increasingly difficult. The bubbles rising in the pool serve as a visual metaphor for the victims’ collective struggle for breath. By capturing these bubbles in silence, the camera further evokes the suffocation endured by the victims’ families, who were unable to share their stories or uncover the causes of their suffering.

Aligned with the real activist group, the film underscores the perilous ease with which pulmonary fibrosis can destroy a family and the disturbing randomness with which it may strike anyone in Korea. It illustrates how the media can manipulate everyday choices and how such influence allowed the tragedy to continue for more than a decade. By framing Jung’s memory of his late wife explaining that she bought the disinfectant for their son after seeing advertisements on television, the narrative intertwines his grief, his regret at having used the product, and his anger at having trusted labels approved by the government. This flashback is arguably more powerful than any direct documentation of labels or advertisements. The film seeks to remind the public of the need to confront the tragedy collectively by boycotting products sold by these major corporations. Through the presentation of facts and data infused with emotional force, the director and the activist group foster a climate of resistance against corporate power.

It is heartbreaking to learn that children and pregnant women were effectively murdered by the humidifier disinfectant. It is heartening, however, to witness the courage of those who stood with the victims, particularly the doctors and lawyers who contributed their labour without payment. At the same time, the audience is repulsed by scenes depicting unscrupulous CEOs who use profits from the disinfectant to fund lavish parties involving sexual services. A profound sense of helplessness settles in near the end of the film, when neither government committees nor corporations show any willingness to take responsibility for the disaster.

Intertwining the issue with the dynamics of capitalist development, the film depicts victims struggling to raise funds for legal action, while multinational corporations express greater concern over the death of a single United States citizen than the deaths of thousands of Koreans, fearing that litigation in the United States could lead to bankruptcy. The CEO is portrayed as a villain who declares his admiration for Korea as a place where wealth commands obedience. This is followed by a scene in which he stresses his British citizenship, thus rationalising his business strategy in Korea. In the feature film, this villain is ultimately defeated by a group of conscientious Korean citizens. In reality, however, the CEO of the Korean branch of the British company Oxy did not apologise until five years after the investigation into the humidifier disinfectant disaster. The CEO, an Indian British national, was in fact promoted to the company’s Singapore branch. Protesters continue to work tirelessly to raise international awareness of the tragedy and to seek his imprisonment.

I conclude this essay with a consideration of a television commercial (below). The LG (“Life’s Good”) humidifier advertisement for Korean audiences features a mother and her children living in a pristine white mansion, happily sharing purified air.

Reflecting on the representation of air in the film, I draw on the term “atmosphere” in affect theory to examine how social life is grounded in the nuclear family, where an ostensibly sensible pursuit of hygiene becomes entangled with anxiety. Atmospheric thinking enables a theorisation of the relations that bind environment, bodies, and emotions. In the film, the primary victims of lung disease are women and children, conventionally positioned as care recipients. In the name of providing better care, families are encouraged to fear for their household’s well-being and to invest in products that promise enhanced air quality, such as humidifiers. To ensure that these humidifiers remain “clean,” disinfectants became the next bestseller. The blurred boundary between hyper-hygiene and toxicity is thus intertwined with consumerism and the social structures and stereotypes that sustain it.

In line with Michael Cohen’s assertion that “by definition, ecological literary criticism must be engaged. It wants to know but also wants to do […] Ecocriticism needs to inform personal and political actions” (2004, 7), the activist group responding to the humidifier disinfectant disaster sought to encode both personal and political agency through the film Air Murder. Such actions may inspire meaningful change within the community and prompt the Korean government to re-examine its legal system. Yet my concern as a film scholar, writing from outside Korea, is to scrutinise the harm that capitalist systems inflict on communities worldwide, and to practise ecocriticism through the study of film and media. Through an atmospheric mode of analysis, I explore how, and in what ways, the air itself has murdered.

Works Cited

▚ Cohen, Michael P. “Blues in the Green: Ecocriticism under Critique”, Environmental History 9.1, 9–36. 2004.

▚ Hsu, Hsuan L. Air Conditioning. New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2024.

▚ LG Humidifier [korea commercial]. YouTube. August 3, 2014. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=unIysUWLR9Q

▚ Yong-sun, Jo. Air Murder. Master One Entertainment. 2022.

How to cite: Chung, Ai-Ting. “Toxic Humidifiers and Atmospheric Thinking in Air Murder.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 21 Nov. 2025, chajournal.com/2025/11/21/air-murder.

Ai-Ting Chung specialises in East Asian cultural studies. She has written essays for Animation Studies 2.0 and Taiwan Insight. She is currently working as a film scholar developing her research on ecocinema in East Asia. She has contributed a chapter on anime and media theory to the forthcoming volume East Asian Ecocinema to be published by Edinburgh University Press in 2026. She is also launching a book project that contextualises film and media theories in Japanese cinema, examining the relationship between arthouse cinema and ecocinema.