茶 FIRST IMPRESSIONS

茶 REVIEW OF BOOKS & FILMS

[REVIEW] “Light, Heat, Power: Rescuing the Modern in Leo Ou-fan Lee’s Shanghai Modern: The Flowering of a New Urban Culture in China, 1930-1945” by Victoria Green

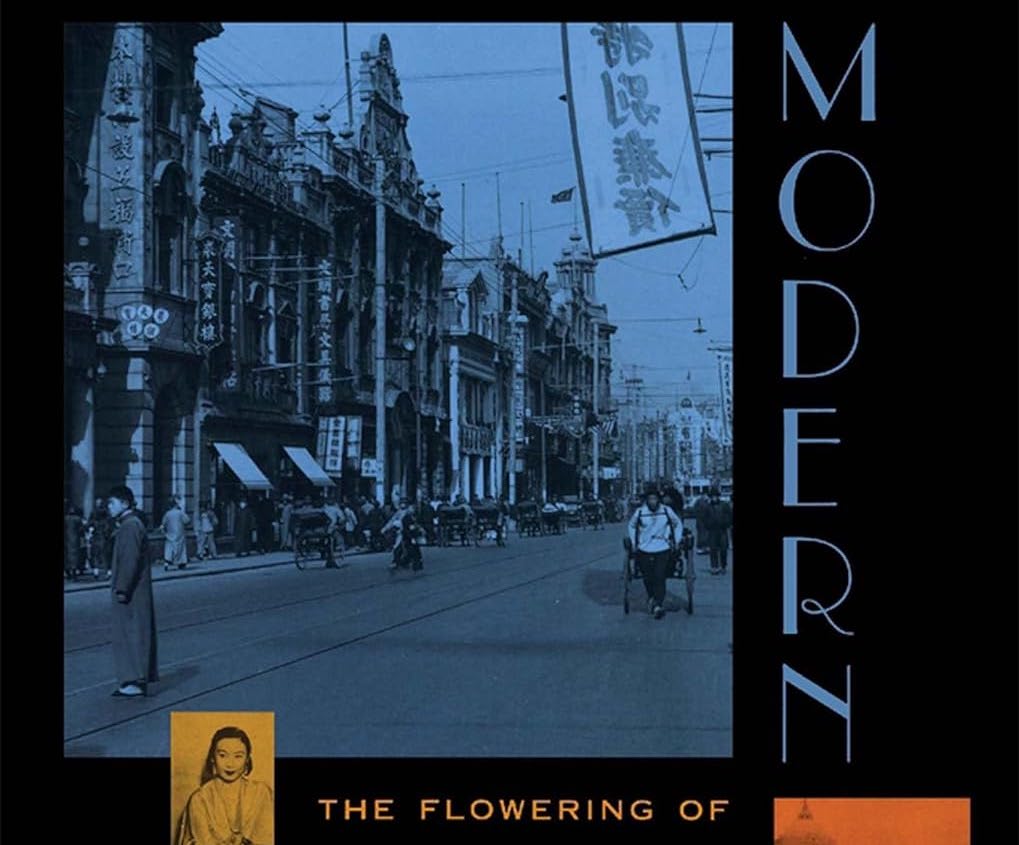

Leo Lee Ou-fan, Shanghai Modern: The Flowering of a New Urban Culture in China, 1930-1945, Harvard University Press, 1999. 409 pgs.

“I know I did not write well. I was able to excite the interest of my readers merely because I had learned methods of psychoanalysis from Schnitzler, Freud and Ellis which I used in my writings. … My works do not occupy an important position in China’s new literature. At most it was a literary experiment of a young Chinese writer who inclined towards modern Western literature sixty years ago and who was neglected before he had the opportunity to develop.” —Shi Zhecun1

Years ago, a friend was discussing a lecture he had attended at National Taiwan University, in which the lecturer claimed that Chinese literature was decades behind the times and that literary movements such as postmodernism were rushed and even senseless, for postmodernism requires the full development of modernism first. This idea shocked me. How could it be possible? Because my first entry into Chinese literature was the fiction of Eileen Chang, I was certain—arrogantly so—that this lecturer had to be wrong.

Leo Ou-fan Lee’s 1999 work of literary criticism, Shanghai Modern: The Flowering of a New Urban Culture in China, 1930–1945, set me straight. While Chinese modernism as a literary movement began to blossom in the 1930s and 1940s, it was cut off before its full flowering. Although many literary and artistic endeavours were disrupted by the Second World War, the thread was picked up afterwards, and the horrors of that period were endlessly woven and rewoven. In Chinese literature, however, there was a significant rupture with the past, and in the ensuing turmoil the works of modernist urban writers of the 1930s and 1940s were largely forgotten.

In China, the dominant portrayal of Shanghai was of a city of excesses, a corrupting influence, a hell where workers were massacred and toyed with by foreign powers. In Taiwan, Lee describes a general neglect of the Chinese literary pioneers of the generation just before his own and a time when he and his classmates read Western modernist literature as if it were new, even launching what would become a highly influential modernist literary journal (Modern Literature) in the 1960s: “We had made what we considered to be a major ‘discovery’ at a time when High Modernism had already passed its creative prime” (p. xiii).

His personal connection to the subject, in which he and his classmates, unaware of the creative scene in 1930s Shanghai—where many young men launched literary journals after being inspired by European modernism—did the same in the 1960s, enables him to describe and observe that earlier scene closely as a peer rather than as an historian puzzling out a distant time. Rather than writing off modernist-influenced works as derivative, Lee argues that the Chinese adaptation of modernism was far more innovative and influential than is often assumed.

In order to understand these artists and the world they described, Lee first sets out their city, both its physical geographic layout and its media landscape of ideas. Physically, it was a city divided into the foreign and the local, with the International Settlement, the French Concession, and foreign-owned factories geographically separated from local residences: “there was a widening gap between the still traditional Old City, with its narrow alleys, small shops, restaurants, and teahouses, and the highly modernised International Settlement, with its high-rise apartment buildings, department stores, and movie palaces” (p. 37). For local city dwellers, modernity was geographically associated with the foreign.

Yet it would be too simplistic to suggest that to be modern was merely to be foreign, for the modern was rapidly integrated and developed locally. Everyone in the city had a mania for cinemas, and in Shanghai cinemas sprang up more profusely than in nearly any other city in the world. The built environment boasted the gleaming presence of an art deco skyline and orderly public parks that offered nature as something to be consumed. Large indoor department stores offered a completely new experience of purchasing luxury items. Coffeehouses allowed men and women to interact more intimately in public than before (and featured prominently in many contemporary romance novels) and dancehalls commodified those same romantic relationships in an industrial fashion.

The media landscape of Shanghai was as important as its physical one, for it was through the media that Shanghai imagined and presented itself. Series of textbooks and encyclopaedias taught people the principles underpinning modernity, while magazines, advertisements, and films taught them what modernity looked, smelled, and tasted like. It invariably looked like young women with bare arms and high heels, smelled of Florida water and cigarette smoke, tasted of powdered milk and ice cream, and felt like the wind from the seat of an automobile.

Shi Zhecun, Lee’s key informant on literary Shanghai, edited many influential literary journals and used them as vehicles for his own short stories. Shi was an avid admirer of the Viennese modernist Arthur Schnitzler, and in his short stories such as “At the Paris Cinema,” Schnitzler’s influence is undeniable. However, rendering modernist literary techniques into Chinese required intriguing technical innovations that Lee highlights for his English-language readers: “Since in the Chinese language there is no rigid tense system and no pure tense marker nor any strict rules governing the agreement between subject and predicate, it allows even more flexibility in the use of free indirect discourse,” (p. 167) the narrative mode associated with stream-of-consciousness. Not only were the imagery and social relationships of modernism distinctive, but they also had to be conveyed in a written style entirely unfamiliar to earlier Chinese prose.

Liu Na’ou and Mu Shiying were known as pioneers of the “New Sensationalism” school, a Japanese literary movement that Liu was well positioned to import, given his background, for he was born in Taiwan as a Japanese subject and educated in Tokyo. As its name suggests, the New Sensationalism of Shanghai’s writers offered readers a city that was thrilling to the senses, always moving, glittering, and providing the young male protagonists with a never-ending carousel of sexually bold but emotionally unavailable “modern girls.” These authors describe a new “city person” who sacrificed emotional depth in order to cope with the deluge of sensations and the vast sea of people they encountered each day.

Shao Xunmei, having been educated in England and spent time in Paris, brought romanticism and decadence home with him to Shanghai. He was a tastemaker who exhausted his entire family fortune in bringing this vision to life: he imported printing presses, published numerous journals and magazines, opened a bookshop, and helped promote many pioneering comic artists. His own poetry, especially Flower-like Evil, likely strikes present-day readers as shameless in its imitation of Charles Baudelaire’s Flowers of Evil, but Shao Xunmei is better understood as an aesthete responsible for introducing the style of the European fin de siècle to Shanghai. His influence on the works produced at that time is undeniable, for he seemed to know everyone and sponsor everything.

An entire chapter is devoted to Eileen Chang, whose writing represents the crystallisation of Chinese modernism. Born in 1920, she was raised entirely in modern Shanghai; she grew up watching both foreign films and local opera performances, read newspapers and magazines in English, and devoured the romantic Chinese fiction of the Butterfly School. She was always devoted to popular literature, transitioning easily to screenwriting as well. She elevated romantic plots to high literature while never losing her closeness to her readers, effortlessly blending popular elements of Hollywood with the scenarios of traditional popular fiction.

Reading Lee’s work on Shanghai modernism now, more than twenty-five years after its initial publication, English-language readers can find an increasing number of translated works from these pioneers of modernism, but that was not the case when the book was first written. These writers, now considered foundational, were plunged into obscurity soon after 1945 and only rediscovered in the 1990s. Mu Shiying and Liu Na’ou were assassinated by KMT agents, while Shao Xunmei survived longer after falling into poverty, though he was ultimately killed during the Cultural Revolution. Eileen Chang spent the remainder of her literary career struggling in exile, attempting a transition to English-language fiction. Shi Zhecun, Lee’s chief informant, who carried the memory of Shanghai’s literary scene, abandoned his creative work entirely and devoted himself to the study of classical literature as a safer middle ground.

From 1999, when Lee’s book was published, to the present, there has been a rise in both scholarly and popular interest in these architects of Shanghai’s modernism. Liu Na’ou’s legacy has been repatriated in Tainan’s National Museum of Taiwan Literature, a fitting tribute for a native of Tainan, and a far cry from the circumstances in which Leo Ou-fan Lee first encountered his work in a Shanghai library. Shi Zhecun received a surge of public praise and interest before his death in the 1990s, and his works were republished to acclaim. Shao Xunmei’s writing has finally been granted serious scholarly attention for its own literary merits, after having long been relegated to the image of the cartoonish playboy depicted in Emily Hahn’s New Yorker columns. Despite the tragedy of a literary movement cut short by conflict and its authors maligned as colonial puppets, Lee’s work initiated the revival that ultimately rescued their legacies and restored their vision of an urbane and sophisticated life in Shanghai.

- Shi, Zhecun (author), Rosemary Roberts, Paul White (translators), One Rainy Evening, Panda Books, 1994. 187 pgs. ↩︎

How to cite: Green, Victoria. “Light, Heat, Power: Rescuing the Modern in Leo Ou-fan Lee’s Shanghai Modern: The Flowering of a New Urban Culture in China, 1930-1945.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 20 Nov. 2025, chajournal.com/2025/11/20/shanghai-modern.

Victoria Green spent several years living, working, and studying in Taiwan, and she currently works in the legal field in the United States. A fervent believer in the spirit of DIY and freedom of expression, she self-publishes a bilingual literary zine called Frisson, which can be found in local shops throughout the United States and Taiwan.