茶 FIRST IMPRESSIONS

茶 REVIEW OF BOOKS & FILMS

Editor’s note: In “E.T. 3 is Lying in a Coffin Outside Wuhan”, Angus Stewart explores Xiaosha Zhang’s 2018 mockumentary My Son Went to an Alien Planet (E.T. Made in China), situating it within China’s rising science fiction cinema. The film follows a grieving farmer who claims to possess an alien corpse, revealing intersections of grief, exploitation, and belief amid social and economic decay. Stewart compares Zhang’s film to Kong Dashan’s Journey to the West (2021) and TVFilthyFrank’s E.T. 2 (2015), tracing shared themes of abjection, loneliness, and faith in the absurd. Ultimately, alien encounters become metaphors for human despair and hope.

[ESSAY] “E.T. 3 is Lying in a Coffin Outside Wuhan” by Angus Stewart

❀ Xiaosha Zhang (director), My Son Went to an Alien Planet or E.T. Made in China, 2018. 90 min.

❀ Dashan Kong, Journey to the West, 2021. 111 min.

❀ TVFilthyFrank, E.T. 2 , 2015. 8 min. 45 seconds.

Obscurity can be painful. The promise of escaping it is as alluring as a miracle. Yet breakthroughs do occur. Oddities are, on occasion, uncovered.

By 2018, the once “lonely, hidden army” of Chinese science fiction was basking in its ascent from domestic obscurity to global readership. This breakthrough was thanks in no small part to the 2014 English edition of Liu Cixin’s The Three-Body Problem, translated by Ken Liu, which went on to win a Hugo Award in 2015 and earn a recommendation from Barack Obama in 2017. The movement’s cinematic beachhead arrived with The Wandering Earth in 2019, a muscular adaptation of another Liu Cixin epic. Yet one year earlier, a smaller, scrappier alien had already emerged on the shore.

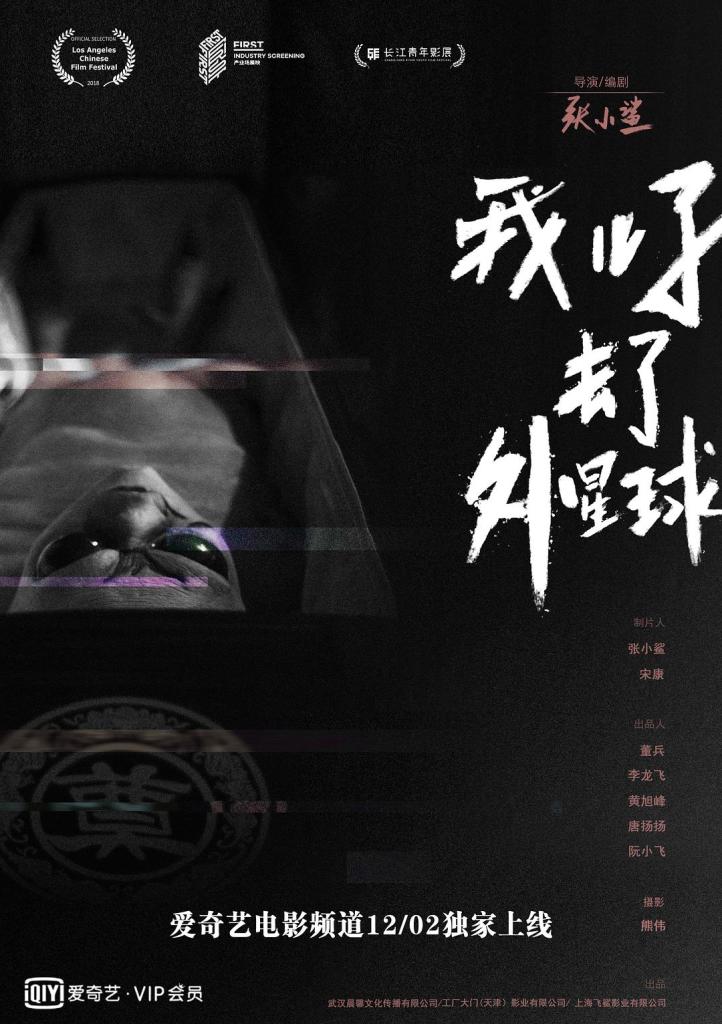

Its title, 我儿子去了外星球, translates as My Son Went to an Alien Planet. A little awkward, but so is the film. There is also an alternative Chinese title: E.T.悲伤乐园, which translates to E.T.: Sad Paradise. The official English title lands closer to the latter: E.T. Made in China (2018), a bit half-baked. But so, arguably, is the film.

我儿子去了外星球, or, My Son Went to an Alien Planet, or E.T. Made in China (2018)

My Son Went to an Alien Planet is shot as a mockumentary. It follows a duo working for a local news channel: the quiet but diligent reporter Wang Xiaoru and her brash right-hand man, videographer Lao Li. They seek out a farmer named Chen Ligen, who claims to possess the body of an alien that died after being caught in his electric rabbit net. UFO enthusiasts in the Middle Kingdom will immediately recognise its lineage from a real 2013 news story, where a man in Binzhou, Shandong Province was punished by the law for making just such a claim.

Chinese science fiction cinephiles might recognise a parallel in a minor scene from the similarly themed alien seeking mockumentary, Journey to the West 宇宙探索编辑部 from 2021. Roughly forty minutes in, the protagonist and his raggedy band of extraterrestrial seekers visit a semi rustic eccentric who shows them his refrigerated “dead” alien. He then makes a swift pivot to offering them expensive souvenirs and shaking a donation box. The alien is an obvious fake, but the scammer’s earnest attitude is strangely infectious.

Casting the net a little wider, a certain cohort of netizens might recall E.T. 2 (see below) from 2015, an eight minute and forty three second video in which the debased YouTuber Filthy Frank, the then alias of George Kusunoki Miller, who is now known as the “sadboy” musician Joji, cures his crushing loneliness by discovering and befriending a four foot alien, presumably made of rubber. He then loses his new friend in a hip hop flavoured haze of avarice and despair. “ET RETURNS TO EARTH AND EXPLORES HUMAN PLEASURE”, the video’s one sentence description blares. What follows is determinedly abject, stupid, and offensive; that is the entire point. Yet, an existential strain runs through the chaos.

Religion, art, music, love—in an endless oblivion of darkness in space, humans are the only species primitive enough to care. You must do what you love. The best things in life will always end in conflict—that is why humans are primitive. Fuck this planet; it is a piece of shit, seriously. If I cannot return to space, then I will snort coke until I die. —E.T.

I cannot prove that My Son Went to an Alien Planet‘s writer-director, Xiaosha Zhang 张小鲨, watched E.T. 2 back in 2015. However, I can confirm the video was available behind the Great Firewall on the Chinese platform Bilibili 哔哩哔哩. It was part of a playlist of core FilthyFrank videos that I watched around 2017, and a 2021 upload of the video remains on the site today. I can also trace a few aesthetic similarities between the works.

Acronym: In its final shot, MSWtaAP compounds on its use of ‘E.T.’ in the English title, panning out from a forensic outline of the alien model with ‘E.T.’ chalked where the human heart would sit

Antisocial: MSWtaAP shares with Miller/Frank’s output a mix of absurd and sometimes childish humour, blended with angst; many scenes break down into yelling and brawls, but there is an undercurrent of inner pain

Rake: Zhang, like Miller’s ‘Frank’ persona, seems to have proved controversial online

Rover: Like many ‘classic’ Filthy Frank videos, MSWtaAP is filmed in liminal spaces—backwoods, backrooms, empty coastline, empty playgrounds. Miller produced videos in ricefields and runways, empty parks and rooftops around Japan and New York, while MSWtaAP was filmed in tumbledown corners of Tianxingzhou 天兴洲, a natural wetland isle in the Yangtse, on Wuhan’s northeastern fringe.

It would be best to curtail the comparisons here. Before doing so, however, it may also be worth noting that Miller, as Joji, has continued to expand his “sad paradise” of hedonistic melancholia. This later work retroactively injects a new meaning into his earlier tale of a depressed rubber alien who burrows into mountains of cocaine to escape self awareness.

Drugs feature in My Son Went to an Alien Planet as well, albeit in a censored and unnamed form. More on that follows.

First, a quick dose of context.

After Wang Xiaoru and Lao Li take a ferry to Tiangxingzhou, interview bemused locals, and stumble upon Chen Ligen, the viewer should not need long to piece together the farmer’s situation. His predicament appears more material than celestial. Around his chicken coops and vegetable plots, Chen runs a simple agritourism hotel, a “fun farm” or 农家乐. This perhaps echoes the 乐园 (paradise) from the film’s alternative title, Sad Paradise. However, an unseen developer wants Chen to sell his land. Its bespectacled negotiator and his troop of heavies are never far off, regularly returning to harass Chen, who in turn almost unfailingly responds by grabbing his trusty pole and charging at them, swinging wildly and yelling blue murder.

So why will Chen not cave in and move on? This is where the alien factors in.

And where did Chen’s strange hope originate? This is where drugs become a factor. After adopting a stealthier approach, Wang and Li identify a sketchy individual who visits Chen at night. At first, the midnight guest exhibits the frazzled, haunted paranoia of one who has ‘seen the truth’. He is the one feeding Chen promises of his son’s return, but these come with requests for large sums of money. It comes as no surprise, then, when Wang and Li eventually witness the man taking hard drugs. He is, in fact, homeless, living nearby inside a beached (human) ship that he has decorated as a makeshift shrine to the alien, a gesture that could be part of his scam or a sign of genuine belief.

Wang Xiaoru, the vessel for the viewer’s conscience, pities Chen and wants to expose the con. Similar concern is shown by the village head, who has correctly surmised the farmer’s psychological impasse is grief. “Don’t let yourself go crazy,” he pleads. However, the Party man also sides with the developer, calmly framing its profit-seeking as an uplifting collective imperative: to further the development of the township, just as others who accepted payment to move to the city have done. He also introduces a practical concern, reminding Chen that the yearly floods are imminent and are predicted to worsen.

Thus, a plague of intangible forces weighs down on Chen.

- The state, and its narrative of progress, entangled with…

- The market, and its narrative of progress. This includes the pattern of urban-rural migratory work that killed Chen’s son, the same system that is depopulating the island and isolating its elderly residents. And the market again, in its imperative to attract, and not alienate, tourists.

- Organised crime, appearing as capital’s enforcers, who often arrive armed.

- Disorganised crime, in the form of a single, desperate addict.

- The media. Wang and Li’s slimy employer, upon receiving their footage, distorts Chen’s struggle by depicting him as a mere attention-seeker.

- Mental ill health, which has already incapacitated Chen’s wife and now seems to be wearing him down, too.

- Climate change, never named explicitly yet encroaching more with each passing year.

It is no wonder that so much of the film channels a mood of quiet abjection, evident in the beaten down faces of the bereaved parents and the detritus and decay scattered across the island in the Yangtze, which sits beneath a bridge carrying motorcars and high speed rail.

The one unseen force promising relief from worldly disappointment is the aliens. For Chen, they can undo death. For the addict, they offer an escape from the planet. For the reporters, there is the promise of a career defining story and a victory over their boss. But the aliens simply do not exist. Or do they? As in Journey to the West, a mysterious final chapter complicates matters.

Aliens or no aliens, shame walks hand in hand with abjection. Few characters escape it. “You worked for decades,” the village head chides Chen, “and for nothing.” The developer’s thugs openly admit, more than once, that they are only harassing Chen out of fear of their employer and shame at having failed at such a basic task for so long. “It’s just a job,” they plead when faced with Chen’s whacking stick.

Even the film requests forgiveness. At its opening we pass through various layers of the fourth wall, hearing but not seeing a cinema audience chatting before a screening commences. There are only empty seats and a blank screen. Then one smartly dressed elderly gentleman sits down with a cigarette in hand, and a somewhat shoddy Chinese shadow puppet scene begins. It features a little alien framed by a tower block on the right and an overgrown dumpster on the left, narrated in the style of a Chinese opera:

This is a news documentary

Because the hard disk that stores the movie footage is damaged,

the movie also has a lot of damage

Therefore, if you feel uncomfortable during the movie, we hope you do not get angry

Later interludes, both operatic and otherwise, also plead with the audience to excuse the film’s technical limitations. The film is peppered with faux digital glitches, from pixelated stitches to static stutter, and frequently jumps from one format to another: widescreen, DV, CCTV, and so on. Various scenes that would have been difficult to produce on a low budget are instead presented using traditional puppetry and opera, such as an extended fight and a climactic, possibly dreamed, encounter with the aliens’ transdimensional vessel.

Multiple scenes within the shipwreck shrine are staged twice due to ‘missing footage’, and are then interspliced. The first version uses the reporters’ hidden cameras to present a static, detached recording of an argument between the original non-professional actors playing Chen and the addict, who appear as skinny, scruffy figures. The second version adopts conventional television drama camerawork and lighting. The “doppelganger” actors for Chen and the addict not only perform in a cosy, clichéd style to match this production value, but also appear noticeably more plump and well groomed. Here, the film’s fragmented approach produces an interesting demonstration of how the shameful and difficult elements of a society can be papered over precisely by depicting them in the default visual language of mainstream media.

In its themes of abjection, despair, and lonely determination, My Son Went to an Alien Planet finds an alien sibling not only in Frank/Miller’s deranged E.T. 2, but also in Journey to the West. That film’s equivalent to Chen Ligen is the washed out magazine editor and true believer, Tang Zhijun. Tang has also lost a child; his daughter died by suicide two years prior. He, too, buries his grief, only able to release his tears after his journey’s end. Like Chen, Tang is a loser in the modern economy. He followed his passion as a science magazine editor but has ended up barely scraping a living through odd jobs, despite the great promise and enthusiasm of his youth. His quest takes him from Beijing into the rural hinterlands and then the raw wilderness, culminating in a quasi divine encounter with ‘the alien’ writ large, inside a hidden cave.

Thus, in each production we find a form of sadness, and a solution to that sadness offered by a real or imagined visitor from another world.

In E.T. 2: a bleak, nonspecific, and mostly juvenile sadness arising from frustration at man’s animal fallibility, solved by self obliteration through toxic male bonding and debauchery.

In Journey to the West: an early midlife sadness stemming from lost potential and broken family ties, solved by questing for the unknown with comrades in tow.

In My Son Went to an Alien Planet: a late midlife sadness, repressed and fermenting into outrage, provoked from multiple angles by a predatory and encroaching market economy, to be faced fearlessly alongside one’s spouse and remedied first by hoped for support from the authorities, and second by an imagined fair exchange with emissaries from a more developed civilisation.

I am left to wonder what sadness, if any, haunted the original scammer in Binzhou. News reports from the time stated that he believed in aliens and wanted to use his fake to persuade others. And about this flavour of earnestness, found in both the real man from Shandong and the fictional Chen Ligen on the outskirts of Wuhan, one must ask: should we view it with scepticism, or feel strangely envious?

How to cite: Stewart, Angus. “E.T. 3 is Lying in a Coffin Outside Wuhan.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 15 Nov. 2025, chajournal.com/2025/11/15/e-t-3.

Angus Stewart is a Dundonian living in Greater Manchester who writes occasional strange stories and essays. His works have appeared in various small publications including Ab Terra, STAT, Dark Horses., and more recently, The Asian Review of Books, Typebar and Big Other. His show, the Translated Chinese Fiction Podcast, is on hiatus. [All contributions by Angus Stewart.]