TIFF 2025

▞ 10. The Archivist’s Film: A Conversation on Kunsang Kyirong’s 100 Sunset

▞ 9. She Was Screaming into Silence: A Conversation on Cai Shangjun’s The Sun Rises On Us All

▞ 8. You Don’t Belong to Anyone: A Conversation on Kalainithan Kalaichelvan’s Karupy

▞ 7. The Paper Boy: On Park Chan-wook’s No Other Choice

▞ 6. Saigon Does Not Believe In Tears: On Leon Le’s Ky Nam Inn

▞ 5. The Need for Change: On Kei Ishikawa’s A Pale View of Hills

▞ 4. The Angel of Death: On Jafar Panahi’s It Was Just An Accident

▞ 3. Of Eros & Of Dust: On Ratchapoom Boonbunchachoke’s A Useful Ghost

▞ 2. Light At The End of the Labyrinth: On Genki Kawamura’s Exit 8

▞ 1. Affairs of the Heart: On Cai Shangjun’s The Sun Rises On Us All

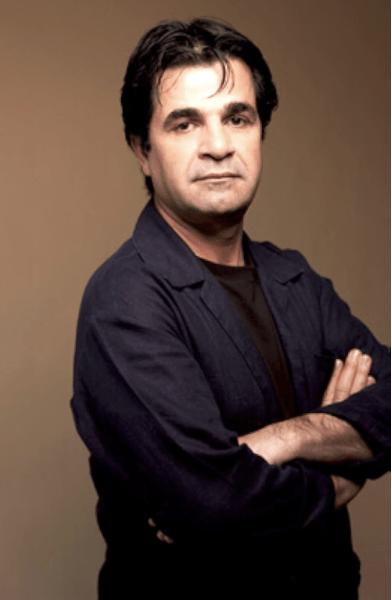

Jafar Panahi (director), It Was Just An Accident, 2025. 101 min.

That Jafar Panahi’s (pictured) newest film, It Was Just an Accident, which won the Palme d’Or at this year’s Cannes Film Festival, begins inside a car is hardly surprising. His cinema has long been drawn to the figure of the driver. Like Abbas Kiarostami before him, and Asghar Farhadi after, Panahi has been fascinated by the cinematic and narrative potential of the moving vehicle. This tendency extends beyond eliminating the need for the two-shot or creating easy depth within the frame: it establishes an interior perspective contained within an external medium.

The film, which at 105 minutes unfolds over a single day, opens at night with a middle-aged couple driving home along a roadside lined with barking dogs. When their daughter suddenly appears in the back seat, evoking Razieh, the seven-year-old protagonist (Aida Mohammadkhani) of Panahi’s debut The White Balloon (1995), our understanding of the dynamic shifts. She asks to turn up the music, reasoning that they are not at home and no neighbours can overhear them. Such a detail, carefully layered into Panahi’s script, only reveals its resonance later. But something is struck on the road, ending their playfulness. The father steps out, his face bathed in red light, and removes the body, his hands stained with blood. “You killed it,” the daughter says on his return. He stirs uneasily as words such as “fault”, “purpose” and “blame” drift into the air.

“What will be will be,” the mother remarks, prompting us to suspect that this incident is the titular accident and to view it as a metaphorical lens for what follows.

When the car later breaks down and the family find a repair shop that allows them to return home, the perspective shifts from the family unit to an individual: Vahid, played by Vahid Mobasseri, familiar to Panahi’s audiences as the submissive landlord in No Bears (2022). A mechanic with chronic back pain, Vahid grows unsettled when he hears, rather than sees, the faint squeak of a prosthetic leg. This sound gradually transforms the driver into an enigma. As time passes, and as Panahi clarifies the initial ambiguity—something he often does explicitly—we learn Vahid’s past. He was a unionised worker, imprisoned along with many others by the regime. He now believes that the driver, whom he calls “The Peg Leg”, was his torturer, the man whose abuses still scar his life. Convinced, he follows him, strikes him with a shovel, and prepares to bury him alive. Yet the man insists he is mistaken: he lost his leg in an accident the previous year. Vahid is left with doubt.

Later, Vahid gathers the torturer’s other victims. These include Goli (Hadis Pakbaten), due to marry the next day, and Shiva (a radiant Mariam Afshari), her photographer and former cellmate. They tell Vahid that he is a man who acts before thinking, though at least he becomes more reasonable. This is contrasted with Hamid (Mohamad Ali Elyashmehr), a paranoid and explosive figure who shakes both the group and the audience out of their clinical detachment, his volatility becoming a disruptive voice of reason. Since the prisoners were blindfolded throughout their captivity, recognition can come only through sensory fragments: the sound of the leg, the smell of sweat, the touch of thighs. The drama derives from their inability to decide if this man truly destroyed their lives, and from their burning need for confirmation before enacting a revenge that might redeem them, even though such justice risks employing the very tools of the oppressor.

“The further you go,” the groom (Majid Panahi) warns his bride, “the more you sink.”

Yet Panahi refuses to go further. More obstacles are laid before the group on their path to truth, including a third-act development that tips the film into farce and attempts to wrench emotion through the threatened innocence of the daughter. Where Kiarostami—in Like Someone in Love (2012), Certified Copy (2010) and Taste of Cherry (1997)—sustained ambiguity in character and motivation without weakening the implications of his films, and where Farhadi—in About Elly (2009), A Separation (2011) and The Past (2013)—constructed puzzles that remained unresolved without diminishing their dramatic force, Panahi seems intent on imitation. But his impatience, his inability to render the passage of time compelling, and his desire to reshape the material into a thriller—driven by a screenplay that is carefully drawn yet riddled with inconsistencies, implausibilities, and an unearned catharsis—diminish its impact.

As in No Bears, where the drama centred on the contested existence of a photograph that unsettled an entire village, It Was Just an Accident ends by leaving us uncertain as to what is real and what is not. The conclusion, recalling Denis Villeneuve’s Prisoners (2013) and seemingly indebted in scope to Incendies (2010), offers a vision of what it feels like to be haunted by the angel of death, which sooner or later will come for us all.

How to cite: Nagendrarajah, Nirris. “The Angel of Death: On Jafar Panahi’s It Was Just An Accident.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 8 Sept. 2025, chajournal.blog/2025/09/08/just-an-acciden.

Nirris Nagendrarajah (he/him) is a Toronto-based writer whose work has appeared in paloma, Polyester, Fête Chinoise, In the Mood Magazine, Tamil Culture, in addition to Substack. He is currently at work on a novel about waiting. [All contributions by Nirris Nagendrarajah.]