茶 FIRST IMPRESSIONS

茶 REVIEW OF BOOKS & FILMS

[REVIEW] “Thammika Songkaeo’s Stamford Hospital: Love and Loneliness in a Capitalist City” by Fathima M

Click HERE to read

Thammika Songkaeo’s

“Twist of Fate”

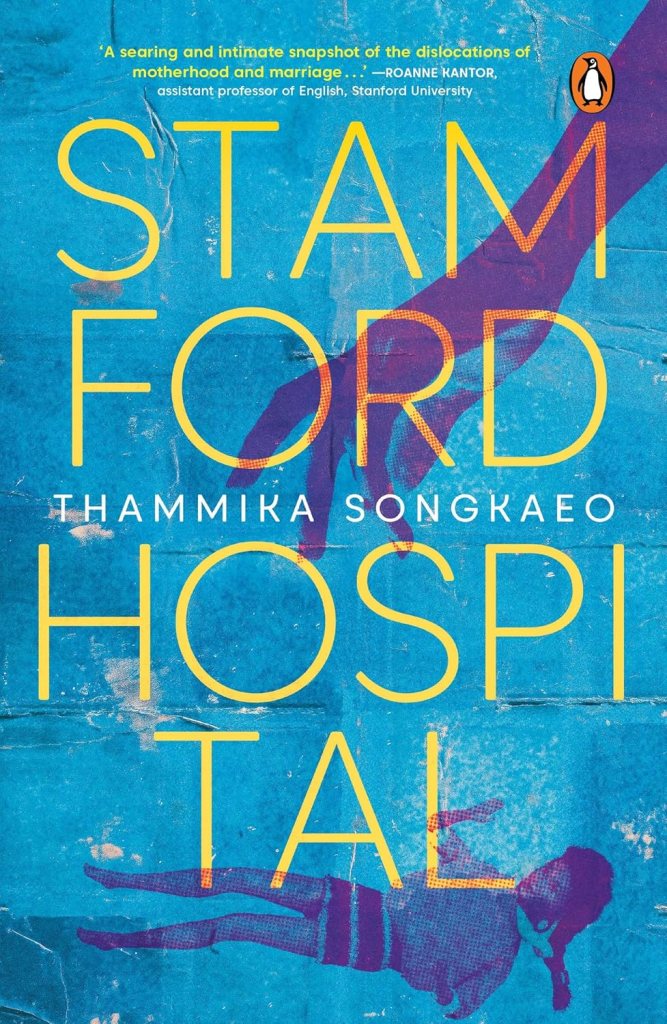

Thammika Songkaeo, Stamford Hospital, Penguin Random House SEA, 2025. 256 pgs.

Stamford Hospital explores the solitude inherent in urban life and the ways in which immigrant mothers in the modern era navigate that solitude while balancing personal ambition and domestic responsibility. For too long, motherhood has been romanticised as a noble ideal—yet the loneliness of overburdened mothers has been largely excluded from mainstream narratives. The novel centres on the life of a young woman, Tarisa, who finds herself trapped in a sexless marriage and overwhelmed by the demands of motherhood. Tarisa and her husband remain emotionally distant, bound by an institution that compels them to cohabit and co-parent. Beyond this shared duty, there exists little genuine connection between them—certainly nothing of a romantic nature.

The novel portrays life after marriage as labour-intensive and unrelenting. The protagonist is frequently depicted avoiding tasks that require her constant attention and physical presence. This is not to suggest that Tarisa is idle—on the contrary, she is intelligent and ambitious, yearning to carve out a life of her own. Yet she finds the endless domestic chores draining, and the attention her daughter demands, profoundly exhausting. She does not wish to be the perpetual centre of attention, but rather seeks solitude and space for herself—a struggle faced by countless mothers. She also longs for sexual intimacy, a desire that has remained unfulfilled since her husband became sterile following treatment for hair loss.

Although the novel begins with Tarisa’s discontent within her marriage, it is not merely another narrative of an ambitious woman acquiescing to the constraints of domestic life. By the novel’s end, we see that her husband, Chris, too, is making earnest—albeit flawed—attempts to salvage the marriage and contend with his own challenges. While Tarisa smoulders with resentment at having relinquished her PhD aspirations, her freedom, and her voice, she nevertheless remains in the marriage. Chris’s efforts, however, remain confined within patriarchal boundaries. He compels Tarisa to abandon her dream of pursuing a PhD in the United States, refusing to relocate. Content with his earnings in Singapore, he fails to grasp the importance of his wife’s desire for a career of her own. Singapore—emerging as the new global North within the global South—is a city consumed by capital. It offers opportunity primarily to those in the financial sector. The city, as Gatsby might say, smells of money. As an immigrant mother in Singapore, Tarisa finds herself doubly isolated—estranged both from her surroundings and from herself.

Marriage is a reciprocal endeavour—one that demands both time and effort. In a capitalist world, however, time and space for intimacy become increasingly elusive. The culture of overwork and the relentless hustle that pervade many societies have created a world in which adults are perpetually exhausted. Tarisa and Chris are no exception—they are both worn down. The boundless demands of parenthood and the unyielding pressure to achieve financial independence become deeply dispiriting. The novel deftly portrays the darker undercurrents of capitalism. An overworked Tarisa is denied both a raise and maternity leave. She is ultimately compelled to leave her job, as the dual burden of full-time employment and motherhood proves untenable. There are egregious moments in the novel when Tarisa’s employer advises her not to prioritise motherhood, cautioning her against making her child the centre of her world.

Capitalism thrives first on the control of our time—even before the control of our money. Long working hours, with scant allowance for anything beyond labour, render it a profoundly exploitative system. Moreover, it leaves individuals increasingly isolated—separated from family, devoid of support, while the state offers little by way of community structures to assist women who find themselves alienated and adrift.

The novel takes its title from the hospital where Tarisa’s daughter, Mia, is admitted for a minor infection. For Tarisa, this brief reprieve from motherhood—even partial—is a source of relief. The hospital, where the nurses tend to Mia with care, becomes a rare sanctuary: a space where Tarisa is not solely responsible for everything. Her exhaustion and loneliness are not merely personal—they signify a broader, collective crisis in which both men and women find themselves more isolated than ever before. The erosion of intimacy and sexual desire is as much a medical condition as it is the product of widespread fatigue. The author, Thammika Songkaeo, captures Tarisa’s emotional landscape—and that of others—with meticulous precision. At times, the tedium of their lives is so acute that the reader, too, feels the weight of each tantrum, the indifference of Chris, and the pervasive absence of communication that haunts not just their relationship, but those of nearly everyone around them. The city becomes a site of profound loneliness and ennui, where capitalism—coupled with the absence of human connection—renders life both monotonous and burdensome.

How to cite: M, Fathima. “Thammika Songkaeo’s Stamford Hospital: Love and Loneliness in a Capitalist City.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 18 Jul. 2025, chajournal.com/2025/07/18/stamford-hospital.

Fathima M teaches English literature in a women’s college in Bangalore, India. She likes hoarding books and visiting empty parks. [Read all contributions by Fathima M.]