茶 FIRST IMPRESSIONS

茶 REVIEW OF BOOKS & FILMS

[REVIEW] “The Party’s Interests Come First: Joseph Torigian’s The Life of Xi Zhongxun, Father of Xi Jinping” by Susan Blumberg-Kason

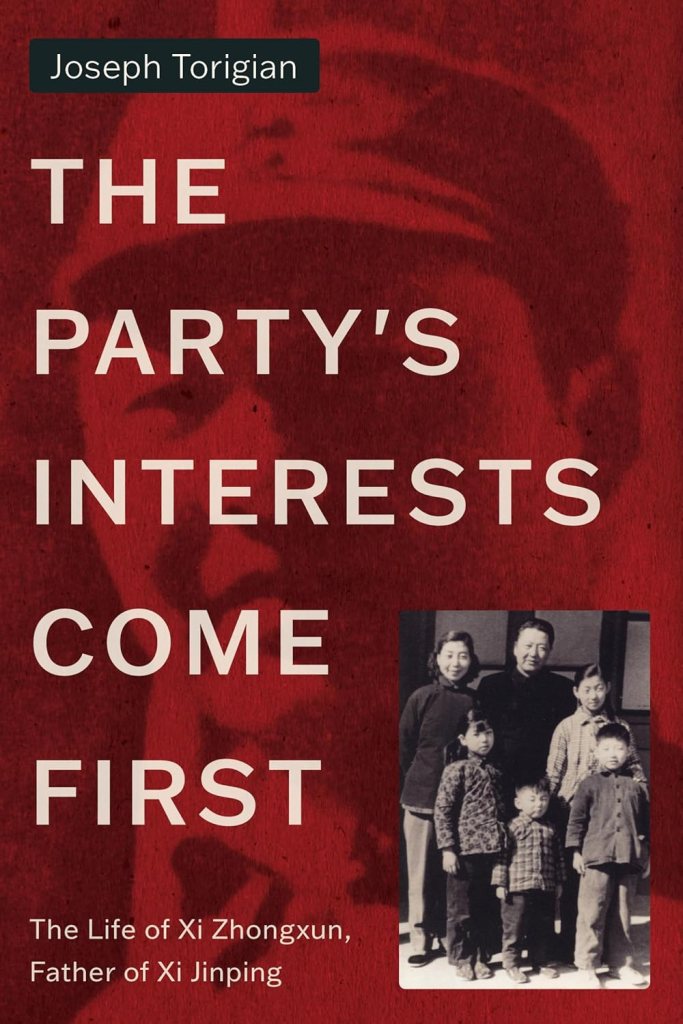

Joseph Torigian, The Party’s Interests Come First: The Life of Xi Zhongxun, Father of Xi Jinping, Stanford University Press, 2025. 718 pgs.

During the early months of the pandemic, the Hong Kong Studies symposium hosted Professor Joseph Torigian of American University to speak about his research on Xi Zhongxun, father of Xi Jinping, for a book he was then in the process of writing. Torigian captivated the Zoom audience with compelling accounts of Xi Zhongxun’s career—first as a revolutionary, and later as the senior government official overseeing Guangdong province. These accounts, among others, left the audience eager to read the eventual publication. The Party’s Interests Come First: The Life of Xi Zhongxun, Father of Xi Jinping is now finally out, and it has proven well worth the wait.

Joseph Torigian presented a paper entitled “Fathers and Sons—Hong Kong and Xi Jinping’s Father Xi Zhongxun” at the Hong Kong Studies symposium “Hong Kong & Elsewhere” in July 2020. Via.

From the outset, Torigian makes clear that his objective in writing Xi Zhongxun’s biography was not to explore the dynamics of father and son, nor to speculate on how père may have influenced fils, but rather to chart the course of the Chinese Communist Party’s history through the prism of a figure who has not always received his due recognition. Torigian also notes in the opening chapter that while Western scholars are often quick to categorise Chinese leaders as “good”, “bad”, “leftist”, or “rightist”, such reductive labels do little to illuminate the complexity of a figure such as Xi Zhongxun. The book’s title more accurately reflects Xi’s character and his political career, which spanned more than half a century. Indeed, Mao himself declared in the 1940s that Xi Zhongxun consistently placed the Party’s interests above his own—frequently to his own detriment.

Xi became politically engaged at the tender age of thirteen, when he joined a youth organisation run by Communists. He began to study Marxist thought and, before long, entered the Communist Youth League. Years later, Xi would reflect that one of Communism’s greatest appeals lay in its ready access to a wealth of books and newspapers. He remained steadfastly committed to the cause for the remainder of his life.

As a teenager, he fought in the Red Army in the Shaanxi–Gansu–Ningxia region of northwest China, laying the groundwork for the Yan’an Communist headquarters. Following the establishment of the People’s Republic in 1949, Xi became the principal leader of the Northwest Bureau, which included Tibet and Xinjiang. A natural diplomat, he cultivated cordial relations with the Panchen Lama and attempted to mend ties with Soviet advisers as Sino-Soviet relations began to deteriorate. Although Xi appeared to be succeeding in his role, other senior figures in the Northwest during the early years of the PRC—Gao Gang and Peng Dehuai—were purged, and it was only a matter of time before Xi met the same fate. This occurred in the early 1960s, when he was placed under house arrest.

Prior to his political downfall, both Xi and his second wife, Qi Xin, worked so extensively that they sent their four children to a boarding school in Beijing for the offspring of high-ranking officials. Xi Zhongxun was frugal, and his children—including Xi Jinping—wore hand-me-downs and bathed in used water when at home. Yet his frugality could also be his most endearing quality in forging connections with others, and his personal motto was “forging”—as in forging ahead regardless of obstacles. And there were many. The notion of “eating bitterness” is one that older generations in China often wear as a badge of honour, and it was through this shared experience of hardship that Xi found common ground with people from diverse backgrounds. He was among the most empathetic senior officials working on United Front relations—for instance, with former Kuomintang members who had remained in China, religious minorities, and overseas Chinese. Yet his empathy did not always extend to those who suffered on account of their minority status—namely Tibetans, Uyghurs, and others.

Many parts of this book elaborate on well-known episodes in the history of the People’s Republic of China, with Xi frequently at the centre. One particularly striking section recounts the period when Xi was dispatched to Guangdong—after the Cultural Revolution but prior to his full rehabilitation. In April 1978, he began as second-in-command in the province, but soon assumed the role of First Secretary. Three months later, he travelled to the China–Hong Kong border, where he observed a stark contrast between the two regions.

A particularly dramatic moment occurred during a trip to Sha Tau Kok, where Chung Ying Street was controlled on one side by the mainland and the other side by Hong Kong. On the capitalist side, business was brisk, but in the mainland, the scene was desolate; buildings were run-down, and weeds were growing in abandoned areas. “Liberation happened so long ago, almost thirty years,” Xi said. “That side is prosperous, but on our side, everything is shabby.”

Xi supported the Special Economic Zones, although they were established after he left the region to return to Beijing in 1980. Torigian notes that it was not Deng Xiaoping but Hua Guofeng who initially championed the SEZs. And although Xi firmly believed in the SEZs, he did not at first support the household responsibility system—a reform granting peasants the right to farm their own land, in contrast to the collective agricultural model that had prevailed since the 1950s.

The book reads like a Cold War thriller, particularly following Xi’s return to Beijing in the early 1980s. He rose to become one of the senior Party leaders in the central government, as Deng Xiaoping and Hu Yaobang found themselves increasingly at odds. Xi felt caught in the middle: while he sympathised with Hu, he could not bring himself to oppose Deng. Though a reformer, Xi also prized stability and had a deep aversion to disorder. The decisive turning point, as history would reveal, came with Hu’s death in the spring of 1989. The Tiananmen massacre followed shortly thereafter, and Xi did not speak out on behalf of the students. A year after Tiananmen, he returned to Guangdong, where he spent the final dozen years of his life in the semi-tropical environs of Shenzhen.

Xi Zhongxun devoted his life to the Party and found enduring hope in the virtues of the old revolutionaries. No world leader today would live in a cave or bathe in reused water, yet for Xi Zhongxun and his generation, there was honour in this austere vision of nation-building. While many opportunities were missed during his tenure in the Chinese Communist Party, it is unrealistic to imagine that a single individual could have opposed such a powerful centralised system. Torigian wisely reminds readers at the close of The Party’s Interests Come First that it is unhelpful to view CCP leaders through the binary lens of “good” or “bad”, as is often the tendency in the West. Midway through the book, Torigian reflects on Xi’s post–Cultural Revolution years—a single paragraph that encapsulates his decades-long career in the CCP:

In certain ways, Xi shared critical views of the past—he certainly loathed the Cultural Revolution. He was so optimistic about the post-Mao future that he believed the party’s message was powerful and persuasive. At the same time, however, one of the most unambiguous lessons of the Cultural Revolution for Xi was the need for stability and unity. A clear fear of chaos thus shaped Xi’s reactions. When dialogue did not work, he did not shrink from more repressive methods.

How to cite: Blumberg-Kason, Susan. “The Party’s Interests Come First: Joseph Torigian’s The Life of Xi Zhongxun, Father of Xi Jinping.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 16 Jul. 2025, chajournal.com/2025/07/16/xi-zhongxun.

Susan Blumberg-Kason is the author of Bernardine’s Shanghai Salon: The Story of the Doyenne of Old China, a 2023 Zibby Awards finalist for Best Book for the History Lover. She is also the author of Good Chinese Wife: A Love Affair With China Gone Wrong and the 2024 Zibby Awards winner When Friends Come From Afar: The Remarkable Story of Bernie Wong and Chicago’s Chinese American Service League (University of Illinois Press, 2024). She is the co-editor of Hong Kong Noir and a regular contributor to the Asian Review of Books, Cha and World Literature Today. Her work has also appeared in the Los Angeles Review of Books and PopMatters. Visit her website for more information. (Photo credit: Annette Patko) [Susan Blumberg-Kason and ChaJournal.]