茶 FIRST IMPRESSIONS

茶 REVIEW OF BOOKS & FILMS

[FIRST IMPRESSIONS] “The Legacy and Brilliance of Hong Kong Crime Novels: Charles Philipp Martin’s Rented Grave” by Susan Blumberg-Kason

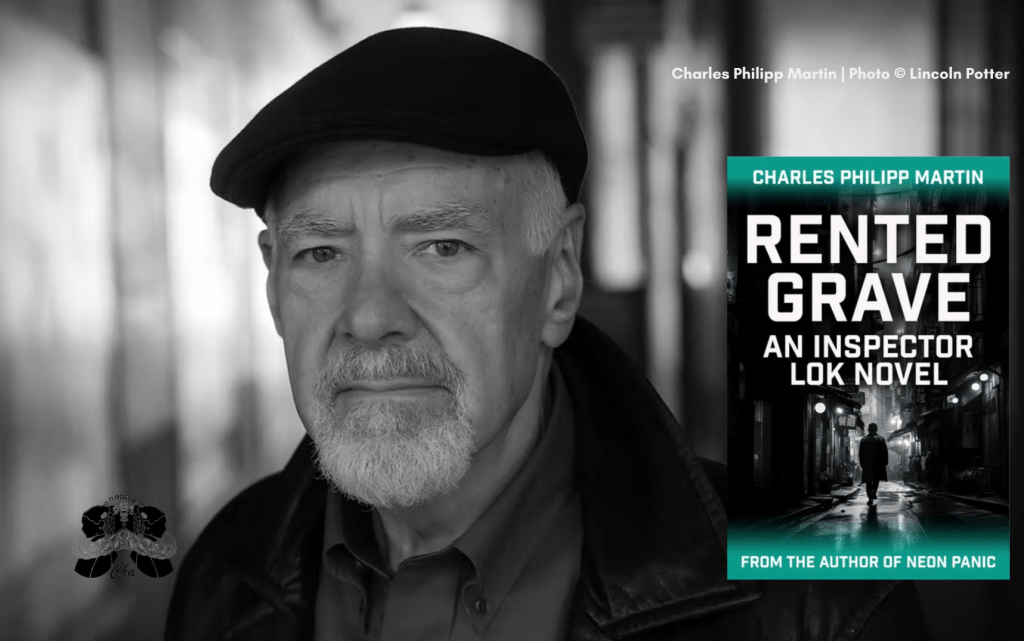

Charles Philipp Martin, Rented Grave: An Inspector Lok Novel, Level Best Books, 2024. 305 pgs.

There is something about Hong Kong that lends itself particularly well to crime fiction. Compact and easy to navigate, the city also maintains a tightly controlled border—allowing criminals in these narratives to move through crowds and vanish into the urban maze, yet without the easy avenues of escape afforded by larger nations. Then there is Hong Kong’s complex history: once a British colony that offered refuge to millions of Chinese fleeing war and turmoil on the mainland. Before it became a colony, after it was returned to China, and throughout the intervening 150 years, Hong Kong has remained a place where people come to begin anew. Though it has frequently been depicted in police dramas—on television, in cinema, and across the pages of crime novels and thrillers—Hong Kong, in reality, ranks among the safest cities in the world.

I was first introduced to Hong Kong through crime fiction forty years ago, when my mother recommended William Marshall’s Yellowthread Street mysteries, set in a fictional district known as Hong Kong Bay. The novels centre on a diverse team of police officers—some British, some Chinese—and span sixteen volumes published between 1975 and 1998, straddling the pivotal moment of the 1984 Joint Declaration.

John Burdett, best known for the Bangkok 8 series, released a stand-alone police thriller, The Last Six Million Seconds, in January 1997—just six months before the Handover. The late Feng Chi-shun authored two collections of Hong Kong crime tales, Hong Kong Noir and Kitchen Tiles. Chan Ho-kei, writing in Chinese, has produced several police thrillers, two of which have been translated into English by Jeremy Tiang in the past decade. His novel The Borrowed is a particular favourite, chronicling five decades in the life of a distinguished police inspector.

Charles Philipp Martin is another crime writer whose journey began in Hong Kong, where he played bass in the Hong Kong Philharmonic Orchestra before turning to writing. During his years in the city, he penned a column for the South China Morning Post and hosted programmes on Radio Television Hong Kong. His debut crime novel, Neon Panic, appeared in 2011, and he contributed to Hong Kong Noir, an anthology I co-edited with Jason Y. Ng in 2018. Both Neon Panic and his short story “Ticket Home” in Hong Kong Noir feature his recurring protagonist, Hong Kong Police Inspector Herman Lok. Martin now returns with another Inspector Lok mystery in Rented Grave.

The meaning behind the title of his new novel is revealed more than halfway through the narrative, as Lok reflects on his late grandfather and contemplates the next stage in the mourning process.

Lok calculates that in two years it will be time to disinter his grandfather, have his bones cleaned and placed in the columbarium up the road. Such a temporary place, Hong Kong. People leave to study abroad, to retire in Canada. Even the graves are rented.

But for most of the characters in this story, Hong Kong is not a mere stopping point—it is home. The year is 2003, six years after the Handover, when the driver of a Hong Kong tycoon named Mo Tun is mistakenly murdered; Mo Tun himself was the intended target. Amid the chaos, Mo Tun’s young grandson, Bonitus, is abducted and held for ransom in a vacant Wan Chai flat. This is no mere act of settling a business score. The roots of this crime reach back decades, to northern China, where Mo Tun once believed he had killed a colleague named Yang—just as he was preparing to flee south to Hong Kong. As he would come to learn, following the murder of his driver and the abduction of his grandson, Yang had not, in fact, perished in the 1960s.

The central mystery in the narrative is not so much what happened during Mo Tun’s failed assassination, but why it occurred and what lies ahead—especially for the young Bonitus, who is not yet a teenager. The plot moves at a brisk pace, sweeping across Hong Kong from Kowloon Tong, Yau Ma Tei and Tsim Sha Tsui, to Central, Causeway Bay and Wan Chai, and back to Shatin and Tsuen Wan, among other districts. Alongside Herman Lok, Rented Grave features several characters also present in Neon Panic, including Old Ko, a detective constable repeatedly passed over for promotion, and Lok’s wife, Dora, who arguably possesses a sharper instinct for deduction than her husband.

In Rented Grave, as in Martin’s earlier work, he pays tribute to Hong Kong and to the people who imbue the city with character and vitality, regardless of their social standing. His characters embody the diverse ways in which individuals—whether from the mainland or farther afield—have made the city their own. He also deftly balances humour with the darker themes of kidnapping and murder. In one scene, as Mo takes a late-night taxi to the Star Ferry and continues on foot to a disco he is having built on Canton Road, he reflects on the exorbitant prices in Tsim Sha Tsui:

The air is still warm and humid from the spring rain that washed over the city a few hours ago. The shops are closed here—all expensive fashion stores with European names like Chanel and Vuitton. It takes five minutes to reach the building that will house The Great Wall Disco. He passes the overpriced restaurant on the bottom floor—eighty dollars for a plate of spring rolls and they call me a crook?—and enters the lobby, where four banks of elevators span the building’s thirty floors, mostly offices.

I cannot help but wonder whether this genre of Hong Kong crime fiction is on the verge of becoming a relic of the past. Martin, along with earlier writers such as Marshall, Burdett, and even the younger Chan Ho-kei, all lived in Hong Kong during a singular moment in its cultural history. It was an era defined by visionary filmmakers like John Woo, Tsui Hark, and Johnnie To, who brought police dramas vividly to life on the big screen. Actors such as Chow Yun-fat, Andy Lau, Maggie Cheung, and Leslie Cheung were central to this cinematic golden age and achieved international acclaim. That same spirit of noir-inflected energy pulses through the pages of Hong Kong crime novels—including Rented Grave.

Are more Hong Kong crime novels on the horizon? So long as writers like Martin, Chan Ho-kei, and others continue to publish, readers will have the pleasure of returning to these gripping, atmospheric tales. Yet it remains uncertain whether new generations of Hong Kong writers will carry this tradition forward—or whether they will turn instead to narrating the city as they themselves have come to know it.

How to cite: Blumberg-Kason, Susan. “The Legacy and Brilliance of Hong Kong Crime Novels: Charles Philipp Martin’s Rented Grave.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 11 Jun. 2025, chajournal.com/2025/06/11/grave.

Susan Blumberg-Kason is the author of Good Chinese Wife: A Love Affair With China Gone Wrong. Her writing has also appeared in the Los Angeles Review of Books‘ China Blog, Asian Jewish Life, and several Hong Kong anthologies. She received an MPhil in Government and Public Administration from the Chinese University of Hong Kong. Blumberg-Kason now lives in Chicago and spends her free time volunteering with senior citizens in Chinatown. (Photo credit: Annette Patko) [Susan Blumberg-Kason and ChaJournal.]