📁 RETURN TO FIRST IMPRESSIONS

📁 RETURN TO CHA REVIEW OF BOOKS AND FILMS

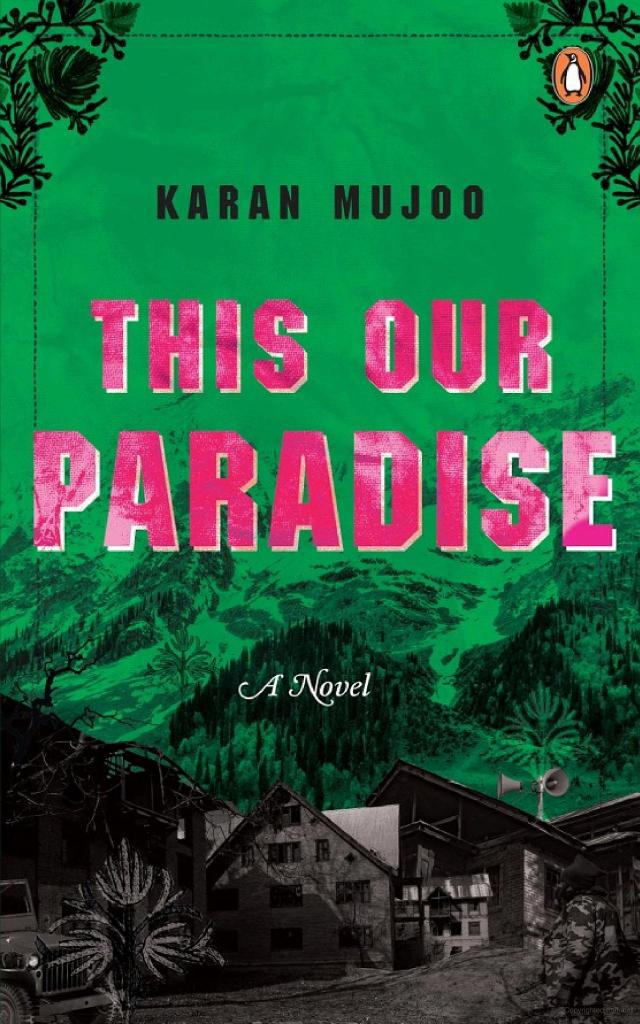

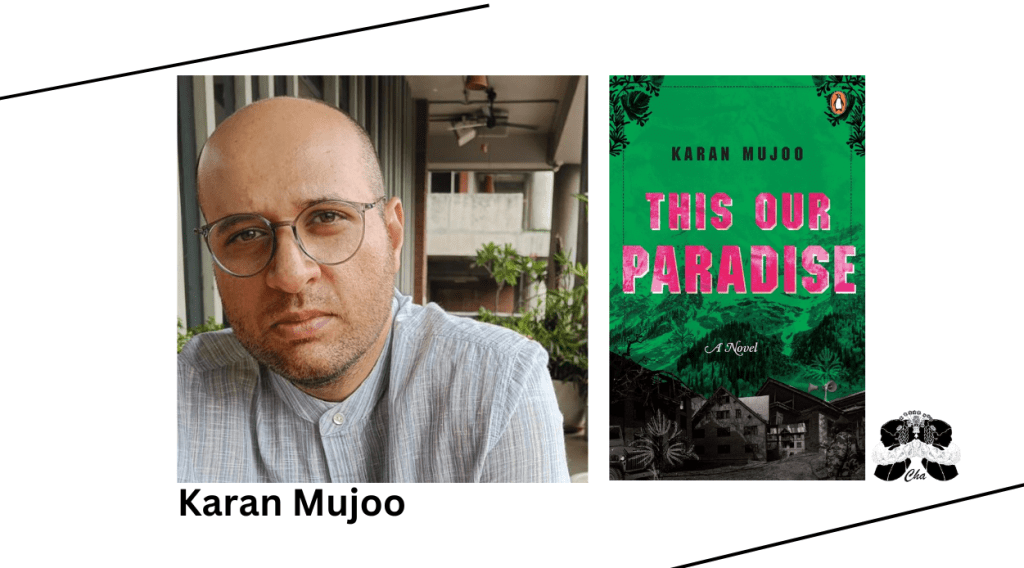

Karan Mujoo, This Our Paradise, Penguin Random House, 2024. 240 pgs.

For some, Kashmir is a paradise of serene valleys and pristine lakes. For others, it is an estranged homeland. And for yet others, it is a struggle to redefine their idea of home. Kashmir exists in multiplicities—each iteration laden with its own grief, resilience, and contested truths. Karan Mujoo refuses to distil Kashmir into a singular, reductive narrative. He neither sanctifies nor vilifies; instead, he meticulously unearths the layered realities of those who call it home, those who have been exiled, and those striving to restore a semblance of normalcy amidst unrelenting strife. He gives voice to the agonised Pandits, forcibly uprooted from their ancestral lands, and the civilians whose existence is perpetually ensnared in the machinery of militancy. This Our Paradise is a title laden with irony, whether deliberate or incidental. The invocation of “paradise” compels the reader to confront the paradox that is Kashmir. From afar, its snow-capped peaks and tranquil valleys evoke the oft-quoted “paradise on earth” sentiment attributed to Khusrau. Yet, beneath this veneer of splendour, what remains?

Set against one of Kashmir’s most harrowing epochs—when militancy and forced displacement devastated the region—Mujoo crafts a profoundly human exploration of a fractured homeland through the intertwined fates of two distinct families. One narrative thread follows a Kashmiri Pandit family, recounted through the unguarded yet strikingly perceptive voice of an eight-year-old child whose world hangs on the brink of collapse. Through this lens, we witness the gradual infiltration of dread as exile becomes an inexorable reality, culminating in the heart-wrenching expulsion from the only home they have ever known.

In contrast, the parallel narrative introduces Shahid, a young Muslim boy whose existence is inexorably entangled in the web of insurgency. Through his story, Mujoo unveils the dichotomy of Kashmiri identity—on one side, the exiled Pandits burdened by their forsaken homeland; on the other, the escalating turbulence of militancy. A remarkable quality of This Our Paradise lies in its ability to encapsulate an astonishing breadth of human experience, political history, and sociocultural discourse into just 240 pages. The novel seamlessly navigates the intersection of the personal and the political, deftly interweaving the threads of historical volatility, institutional decay, and collective disillusionment. Mujoo also lays bare the political undercurrents that shaped the region—Abdullah’s embattled governance, the endemic corruption within state institutions, and the fertile ground these inadequacies provided for anti-state resistance. The novel delves into the intricate mechanics of militancy, exposing the external forces at play, including Pakistan’s instrumental role in fuelling insurgent movements. As systemic dysfunction festered, so too did the people’s simmering discontent, their faith eroded by repeated betrayals. This pervasive sense of disenfranchisement proved to be the breeding ground for insurgency:

Everyone has exploited us—Afghans, Mughals, Sikhs, Dogras, Britishers, Indians. We were always seen as an inferior people. As wretched beings desecrating paradise. All our masters promised prosperity and light. And all of them unleashed death, destruction, and plunder. That’s why we demand azadi; that’s why we must have azadi.

Mujoo’s storytelling reaches its most devastating heights in a passage where personal grief converges with the broader tragedies of a fractured Kashmir. Among the novel’s many heartrending moments, one scene remains particularly searing—the death of a member of the Pandit family. With an aching fusion of sorrow and suppressed rage, Mujoo depicts a family grappling with the unthinkable: the absence of both place and people for the last rites, all while an omnipresent threat of violence looms overhead. Mujoo spares no detail in capturing the brutalities the family must endure—not just the trauma of losing a loved one but the added agony of ensuring the body is not left to decay in a land where even the dead are denied dignity. “The literature of violence had to be lived to be felt. And we were yet to reach the page where our story was written.” Mujoo’s capacity to evoke grief is particularly striking in this passage, where he lays bare the inescapable weight of loss and the internal battle for reconciliation:

It was hard for me to fathom, at that age, what it meant to permanently disappear from life. No grief, no calamity was large enough to stop it in its tracks. How nonchalantly everything continued, as if Vicky had never existed, as if he had never mattered.

Mujoo imbues his narrative with an authenticity that elevates even the most unassuming aspects of life. One of the most striking elements of This Our Paradise is his meticulous attention to food—not merely as a sensory indulgence but as a narrative instrument that encapsulates the rhythms of everyday existence. From the intricate depiction of bread-making to the evocative renderings of kebabs, mutton dishes, and other delicacies, Mujoo seamlessly integrates food into the fabric of his storytelling. This calls to mind Brillat-Savarin’s axiom, “Tell me what you eat, and I will tell you what you are.” He employs food as a conduit for articulating the ineffable—rituals, traditions, and identities that anchor existence. Given the profound role food plays in shaping human experience, it is unsurprising that it emerges as a vessel for self-expression and communal belonging.

Mujoo’s This Our Paradise deserves acclaim not only for its masterful storytelling but also for its nuanced exploration of a land too intricate to be encapsulated within a singular narrative. As the author himself acknowledges, “I cannot provide the reality of events; I can only convey their shadow.” Through lucid and evocative prose, Mujoo breathes life into his deeply empathetic characters. An applaudable narrative choice is Mujoo’s decision to tell the story of the Kashmiri Pandits through the eyes of an eight-year-old child. This perspective is filled with innocence and raw tenderness. Through the child’s lens, we witness the excruciating process of adaptation—moving from a familiar home to a foreign space, struggling to reclaim one’s identity in a land that no longer feels like home, pulsating with uncertainty, hope, and resilience. In contrast, Shahid’s story unfolds through an anonymous narrator, whose detached recounting mirrors the dislocation and sense of unfamiliarity central to the character’s internal conflict. Shahid, ensnared within the turbulent currents of Kashmir’s political upheaval, exists in a perpetual state of flux—his convictions oscillating between conflicting ideologies. Once yearning for a life of simplicity, he ultimately relinquishes this desire, drawn instead towards something grander—a steadfast belief in the movement, in tehreek.

What distinguishes Mujoo’s work is its refusal to confine characters within simplistic archetypes. Instead, the novel presents individuals enmeshed in the relentless tide of historical and political upheaval. He undertakes the formidable task of confronting the human cost of conflict. In its unflinching honesty, the novel dismantles the comforting illusion of comprehension and replaces it with an unsettling yet necessary awareness of what remains unknowable. This Our Paradise is an indispensable contribution to the ever-evolving discourse on Kashmir—a paradise for some, a battleground for others, and an enigma for many. The novel’s fluid narrative, coupled with its unwavering candour, renders it a compelling meditation on identity, memory, and the layered complexities of a land burdened by the weight of multiple histories.

How to cite: Singh, Ananya. “A Fractured Paradise: Karan Mujoo’s This Our Paradise.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 1 Feb. 2025, chajournal.blog/2025/02/01/paradise.

Ananya Singh is a writer. Her work has been published in FirstPost, Deccan Herald, Madras Courier, and elsewhere. She can be contacted via ananyadhiraj7@gmail.com and @anannnya_s on Instagram and X. [Read all contributions by Ananya Singh.]