茶 FIRST IMPRESSIONS

茶 REVIEW OF BOOKS & FILMS

[FIRST IMPRESSIONS] “Lai Wen’s Tiananmen Square: A Coming-of-Age Dramedy Culminating in a Historic Massacre” by Kevin McGeary

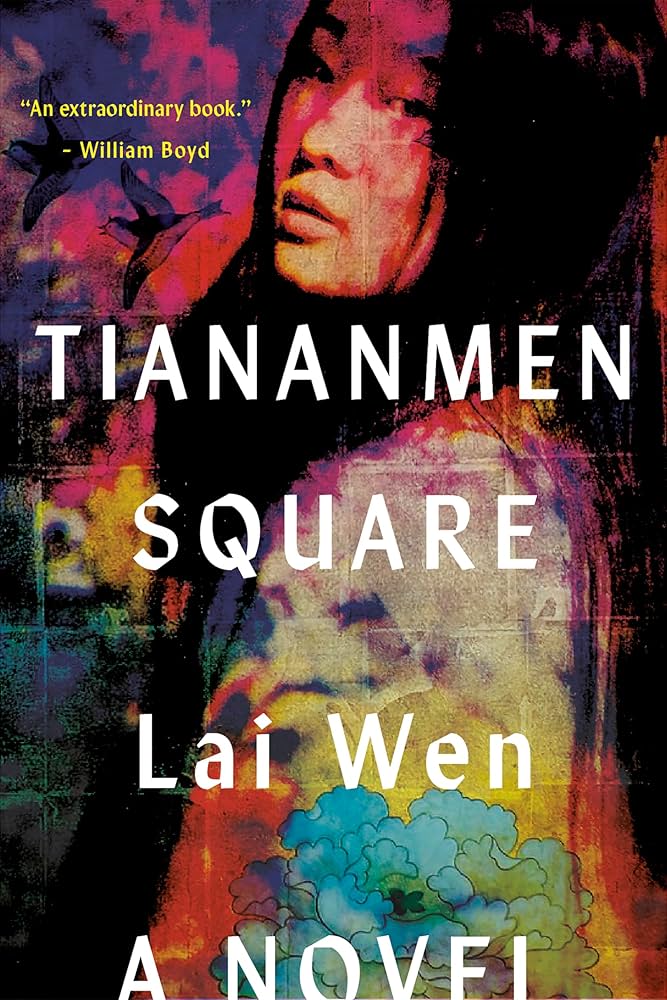

Lai Wen, Tiananmen Square: A Novel, Spiegel & Grau, 2024. 528 pgs.

“In China, you may not be interested in politics. But politics is interested in you.”

In Lai Wen’s novel Tiananmen Square, one character muses, “In China, you may not be interested in politics. But politics is interested in you.”

Although the novel takes its name from the Beijing landmark and culminates in the massacre that occurred there on 4 June 1989, it is predominantly a coming-of-age comedy, rich in insight into life in China and beyond.

The protagonist, Lai, is a child in Beijing in the 1970s. Her childhood coincides with the death of Chairman Mao and China’s emergence from a hermetic, impoverished backwater into an aspiring superpower.

A childish prank results in a clash with the police that both traumatises Lai and foreshadows a far greater confrontation with the authorities. A friendship with a mysterious bookseller draws her towards exhilaratingly different perspectives. The first 500 pages trace the ebb and flow of friendship, ageing and grief, as well as awkward youthful romances. The final scene depicts the protest and subsequent massacre of 4 June 1989.

Two central themes structure the novel. The first is rebelliousness, at times innate to people’s nature and at others an unfortunate necessity. The second is literacy, presented as both an escape from and an improvement upon the status quo, as well as the slender hope that it might enable any of us to leave a legacy.

“Slipping away was something I was good at. I’d had a lifetime of practice.”

Lai herself is not rebellious by temperament. In the second half of the book, she reflects, “Slipping away was something I was good at. I’d had a lifetime of practice.” This timidity appears to stem from her father, whom she describes as a “precise and harmless man”. He is an academic in a nation where his class had recently been derided and even executed as “bourgeois degenerates”.

This stands in contrast to the women in Lai’s family. She reminisces, “My mother was the sun, all heat and fire … my father was the moon, a more melancholy presence.”

The most vivid influence on Lai’s early life is her grandmother, who makes shoes for unbound feet, progressive for her generation. In other words, she takes a traditionally feminine activity, using a needle to stitch items of clothing, and transforms it into an act of rebellion.

The grandmother frequently invokes “old Chinese tradition” to excuse her unladylike and unhygienic behaviour. This prompts Lai to become precociously sceptical about the “questionable practices of adults”.

She also speaks disparagingly of the recently deceased Chairman Mao. Recalling the stench of corpses that accumulated and were cannibalised during Mao’s Great Leap Forward, she rants, “I doubt it was anything compared with the smell that bag of shit gives off in his clean and comfortable mausoleum.”

The grandmother also holds unfashionable beliefs in an afterlife, imagining it as “smoke stealing across the sky” or the subtle movement of a chair beside the bed of someone once known to them.

One of the great loves of Lai’s early life is the written word, which she describes as “light as the air, as distant as the mountains.” She stands in awe of “the names of those who had gone, rendered as eternal as the stars”.

“The poets and peacemakers would always be stamped out by those who had force on their side.”

Yet as she grows older, Lai realises that her devotion to literacy is destined for painful collisions with political reality. As she begins to grasp her country’s politics, she laments, “The poets and peacemakers would always be stamped out by those who had force on their side.”

At university, she falls in with a theatrical crowd. At the same time, she remains acutely aware of the need to work to support her family, asking herself, “Does financial necessity turn everyone into a grey little bureaucrat?”

The most entertaining of her university friends is the vulgar, tomboyish Madame Macaw. Lai observes of her, “One minute you were having a casual conversation, the next her words were ripping out her innards.”

In the spring of 1989, Lai is swept up in political unrest and, narrating with hindsight, reflects, “We had no real understanding of just how vicious those ancient waxwork bureaucrats … could be when their power was threatened.”

The writing is of the highest standard from start to finish, and the final battle scene is itself a masterwork. However, it concludes with a concession to identity politics, transforming a male historical figure into a female one, which may prove off-putting for some readers.

The climactic massacre unfolds less with rebellious fervour than with a sense of sombre inevitability. In the end, overbearing power and its tendency to crush ordinary people appear hardwired into China’s historical DNA.

How to cite: McGeary, Kevin. “Lai Wen’s Tiananmen Square: A Coming-of-Age Dramedy Culminating in a Historic Massacre.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 20 Feb. 2026, chajournal.com/2026/02/20/square.

Kevin McGeary is a translator, Mandarin tutor and author. His short story collection The Naked Wedding was published in 2021. He is also a singer-songwriter who has written two albums of Chinese-language songs. [All contributions by Kevin McGeary.]