茶 FIRST IMPRESSIONS

茶 REVIEW OF BOOKS & FILMS

Editor’s note: Jonathan Chan reads She Follows No Progression (Wendy’s Subway, 2024), edited by Juwon Jun and Rachel Valinsky, as a collective meditation on Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, attending closely to individual essays, poems, and artworks. He demonstrates how contributors engage indeterminacy, translation, dictation, and form as generative practices, carrying Cha’s multidisciplinary legacy forward through attentive reading, historical consciousness, and diasporic experimentation.

[ESSAY] “Reading the Gap: Indeterminacy, Translation, and Legacy in She Follows No Progression” by Jonathan Chan

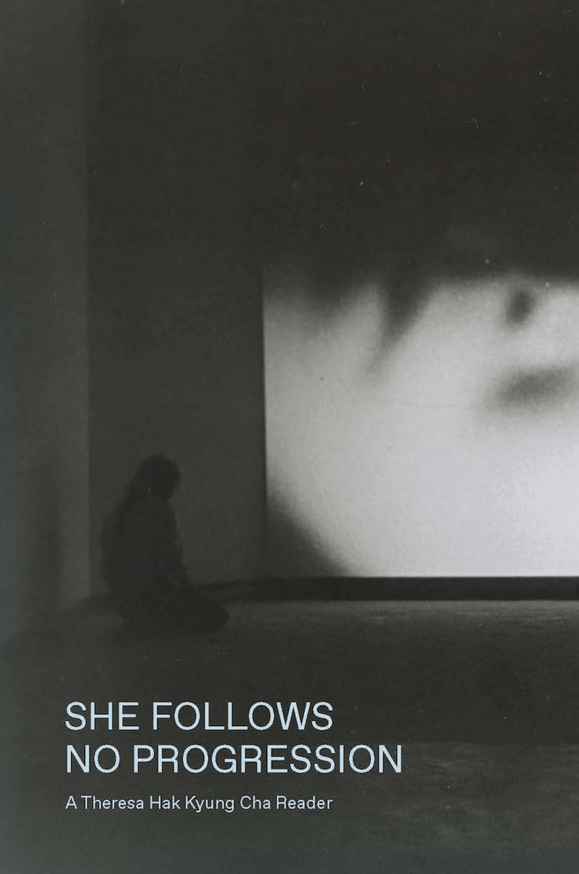

Juwon Jun and Rachel Valinsky (editors), She Follows No Progression: A Theresa Hak Kyung Cha Reader, Wendy’s Subway, 2024. 296 pgs.

It is difficult to overstate Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s continuing influence.

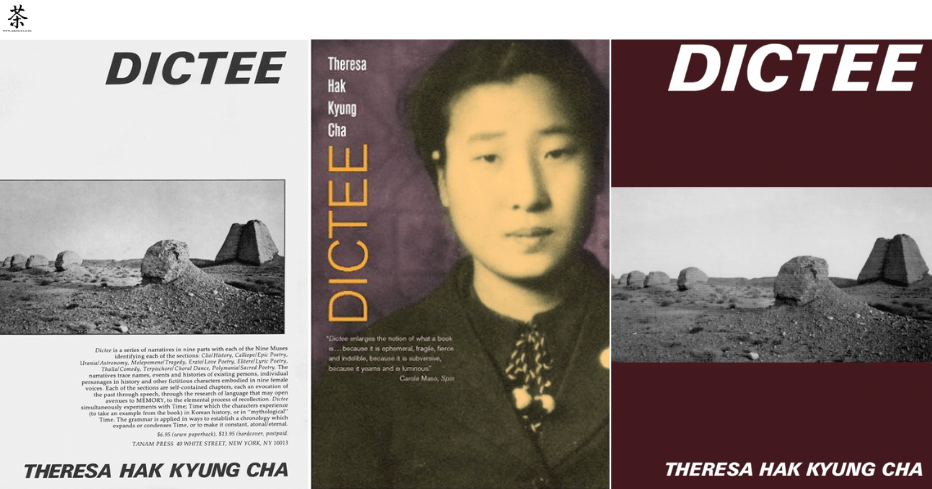

It is evident that, for each contributor to She Follows No Progression, their relationship with Theresa Hak Kyung Cha is personal. Each encountered Cha at a juncture in their lives that left a significant impression, whether in search of an unabashed and experimental Asian American artistic forebear, a precedent who had explored the interstices of Korean and English, or a boundary-crossing artist and writer. It is difficult to overstate Cha’s continuing influence, which looms large in Asian American literary history, her mythos elevated by her untimely murder not long after the publication of what is regarded as her magnum opus, Dictée. Cha’s experiment in disarticulation, multilingualism, plurivocality, and the weaving of text and image has continued to position her as singular in expanding the notion of what an Asian American writer, let alone a Korean American or woman writer, could do in stretching the boundaries of poetic form. This is an avant-garde expressed beyond the strictures of whiteness, as Cathy Park Hong might suggest. My own encounters with Cha proved similarly formative, contextualising Korean American existence within the broader histories of Japanese colonisation, Chinese emigration, war, partition, and domestic unrest in South Korea.

She Follows No Progression, then, finds its origins in a comparable mode. It was envisioned as a multi-genre project during the COVID-19 pandemic, in which writers and artists were invited to respond to or reflect on Cha’s work. The anthology borrows its name from a line of Cha’s in Dictée (1982). Consisting of twenty-three contributions by twenty-five artists, writers, and scholars, the works take a variety of forms, including poetry, reflective essays, academic criticism, and visual art. Each contributor participated in seminars, readings, screenings, and performances at Wendy’s Subway, a Brooklyn-based literary and artistic non-profit dedicated to Cha over several months. As the anthology’s editor, Sanjana Iyer, writes, the project pays particular attention to the “typology of the gap” or the “revolutionary of indeterminacy”, a term introduced by the scholar Una Chung. The lacuna is that which inhibits legitimacy and ultimately enables resistance to assimilation. Cha’s approach, writes Iyer, is an “antidote to the relentless violence of everyday life”, requiring attention to “the way our mouth contorts words” and encouraging the dissolution of “boundaries between genres”.

Admittedly, despite having admired Cha for a long time, my admiration has been constrained largely to her literary work. The pieces in She Follows No Progression that I found most illuminating were those that either revealed new ways of reading Cha’s poetry or expounded upon her work in film and visual art. These contributions were prismatic, offering perspectives on Cha’s oeuvre that I appreciated. Artist Sujin Lee, for example, juxtaposes Cha’s poetry with her film and visual art in the hybrid essay “MOTHER TONGUES 로 번역하기 TRANSLATING INTO 모국어”, which presents two translations of the idea of translation into a “mother tongue”. Lee analyses Cha’s various works, commenting on their orality, examining the ambiguity and imprecision of Cha’s juxtaposition of ostensibly equivalent lines in English and French, and contrasting Dictée with Cha’s single-channel video Mouth to Mouth (1975). The latter, which features a mouth seemingly enunciating passing Korean vowel phonemes as static fills the screen out of sync, gives way to audio of chirping birds, babbling water, and static noise. Lee argues that this static noise forms a third space, in the same way that indeterminacy emerges in Cha’s movement between English and French.

Lee also comments on Cha’s installation Exilee (1980), which features a video playing on a monitor embedded within a Super 8 film projected on a screen. The image shows an envelope covered with snow-like grains, giving way to the impression of a body, as Cha recites a text twice, each iteration a variation of the other, with video and film lights converging to create a complementary and fragmented space. Lee’s commentary is interspersed with presentations of Cha’s poetry, visual art, and film stills, providing a contextualisation that I had not previously been able to access, while also situating Cha properly as a multidisciplinary artist.

Lee comments on the absence of a plural form for “mother tongues” in Korean, translated as “모(국)어”. This finds a parallel in translator and poet Megan Sungyoon’s poetry sequence “M-OTHER-TONGUE-S” presented variously in bilingual Korean and English prose-poetic stanzas and dispersions of words across the page. Sungyoon’s speaker gestures towards similar forms of linguistic indeterminacy, responding to Cha’s writing in Korean:

What if mother’s mother’s tongue—not mother’s mother tongue —is what mother is striving to speak, with many mothers’ mothers’ mother tongue(s) being a national language different from later generation’s mother tongue(s), for there was only a scarcity of nation during mothers’ mothers’ times and even the national language that maintains the same name is a faint, everchanging logic that is only concrete in myth, and to which mother (which one?) unfortunately subjects herself (which one?)

Sungyoon alludes to a sense of incomplete linguistic transmission, ruptured by occupation and colonisation, linguistic erasure, and approximation. It is a form of hereditary constraint. Later in the poem, the speaker ventriloquises another who asks, “Aren’t you scared that we will never be a whole in any language, and that we will remain two thirds in one language and one third in the other”. The poem pays homage to Cha’s own memory of her mother, Hyung Soon Cha, born to first-generation Korean exiles in Manchuria and enmeshed in her own fraught relationship with Korean alongside Japanese and Chinese. Lee locates within this ambiguity, between languages and forms of cultural situatedness, a framework through which to articulate her own “unnamed space” upon returning to Seoul in 2014, having been raised in the United States, and considering the peculiarity and denaturalisation of using English in her work. Sungyoon, also raised between English and Korean and currently residing in the United States, finds in semantic satiation and repetition a comparable new space. Here, one sees Cha’s legacy in lending a form of logic, or perhaps precedent, to other diasporic artists, who refuse a “singular origin” and acknowledge the imperfection of translation, with Lee addressing the “myth” of the homogeneity of the Korean language or Korean blood, and Sungyoon interrogating the notion of linguistic perfection.

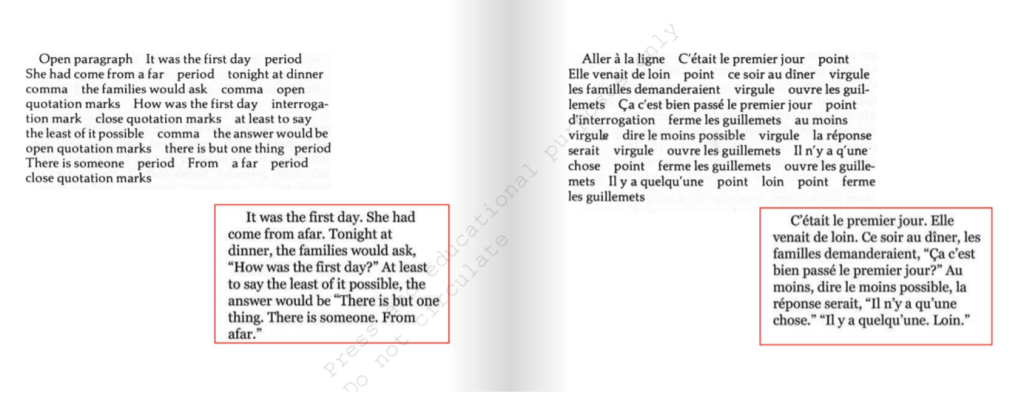

Another essay in the anthology that proved illuminating is the poet Youna Kwak’s “Homonym Error”. Kwak examines the notion of the “dictée”, or dictation, in French-language learning, a process somewhat removed from my own experience as a non-Francophone reader, a distance that has long rendered my appreciation of Cha partial. Kwak narrates how excerpts from Cha’s writing do function as dictation exercises in both English and French, presented as such:

Cha’s poetry enfolds the instructions of dictation. Kwak demonstrates how a response to such dictation might be rendered in both languages, a literal inscribing of a teacher’s spoken instructions. She goes on to describe this as a “limited skill set”, involving a “transposition from aural to written form”, as well as “sound mimicry” and “aural comprehension”. However, Kwak notes that Cha’s renderings resemble neither “standard English” nor “French”, prompting the question of whether the text presented in Cha’s original is “read by the dictator” or “transcribed by the dictatee”. The ambiguity this produces results in an “instability” that refuses “subjugation and colonial rule”, leading again to a “third meaning”, or a thwarting of the “dictée” itself. Kwak observes that Cha removes the diacritical mark in the book’s title DICTEE, suggesting a “wrong sound-word”, while presenting diacritics inconsistently throughout the work, thereby creating frequent instances of homonymy in her French-language writing. Kwak asserts that Cha’s work further eludes two synonymic readings: synonymy with her broader body of work and synonymy with autobiography. She concludes with the notion of being “like Theresa Hak Kyung Cha” as a mode of identification, while recognising the continuing contingency and “incidence” of such likeness. Much of this complexity may be lost to a predominantly Anglophone reader unfamiliar with Francophone conjugations and conventions. Kwak’s essay renders visible Cha’s experimentation and playfulness, particularly her articulation of a “third space” that is cognate with Lee’s analysis in the preceding chapter.

Art historian and scholar Soyoung Yoon, in her essay “The Diabolic Dictée”, further historicises the dictée within French pedagogy, tracing it back to the nineteenth century as a rite of initiation, “due in part to how much spelling and grammar are intertwined” in French. It originated as a test for civil servants under Napoleon I, and the bureaucratic reform of French pedagogy was closely linked to tensions between church and state in shaping public education. The historical “diabolic dictée” was administered by the writer Prosper Mérimée in the court of Napoleon III in 1868, during which the emperor made forty-five mistakes. A single incorrect recognition of a subject could render an entire transcription different. Yoon writes that, despite being a source of dread in schools, the dictée also functions as a site of “singular and intense shame about the bad spelling of one’s mother tongue”, akin to “the rite of confession”. She also attends to the sphere of private influence, describing the importance of mothers in language acquisition, with the mother’s voice serving as an “originary orality” that recodes “the child’s babble”. Yoon draws a connection to Cha’s interest in the ideology of the mother tongue, asserting that the force of Dictée lies in its “deployment of punctuation”, which mimics the grip of the mother tongue over the body and over the body politic. To speak a language is to be subject to its “laws and rules and customs”, with the technicalities of a sentence experienced as a “minefield”. This framework allows Yoon to draw a parallel with the 38th parallel itself, the tragedy of that arbitrary line materialised in the bodies of both people and state. For the exile, driven away by partition and conflict, remembering one’s mother tongue also carries the possibility of hearing “the echo of the infant’s babble”. Yoon cites an additional exchange on the nature and likeness of God, characterised by free association, distraction, and play, asserting that such “poetry” is bound up with “noise” and “babble”. Poetry thus becomes one attempt to recover the babble of the child.

}

Other essays similarly emphasise this sense of absence, or its recovery, inflected through Cha’s position as an editor, critic, and theoretician. In scholar Una Chung’s “Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s Dictee and Notes toward a Practice of Criticism”, Cha’s familiarity with European film theory is foregrounded through her role in publishing Apparatus (1980). The book contains centrefold pages that “cannot be said to contain or not contain references to the essays it anthologises”, provoking an “aesthetics of the gap”, marked by “abruptness” and “immediacy”. Chung argues that Dictee offers “aesthetic renderings of the gap” through “fragments”, “brevity of articulation”, and a “high ratio of punctuation to words”, thereby interrupting “the mind’s habitual motor of concatenation”. This is what allows Dictee to be “empty and luminous” and “free from nation”, particularly when read alongside Chung’s earlier assertion that “Asian America was always fated to become a minority presence as a sign of the desire for its very absence”, an observation that alludes to historical modes of exclusion directed at Asian immigrants.

Writer Anton Haugen gives similar attention to Cha’s editorial past in his piece “How to Silence: On Apparatus and Dictee”. In this brief two-page reflection, Haugen argues that Cha problematises the ideal of enlightenment through spectatorship, with spectatorship figured instead as a form of death. He identifies the recurrence of references to Carl Theodor Dreyer’s film Vampyr (1932), in which the film’s hero, the vampire, “stares through the coffin’s glass, into the camera, to the spectator and reader”. In Dictee, this gesture suggests that “cinema’s capacity to immobilize bodies through the mediation of history becomes the paralysis brought on by postcolonial trauma”. To view the moving image is to enter a séance, a “seductive recursion of post-traumatic alienation”. The deadening effect of spectatorship, Haugen suggests, gives rise to a resolve not to “repeat history in oblivion”. This recalls the 1995 essay “Tracing the Vampire”, in which the actor John Cho argued that Cha’s tenth muse was a female vampire. In a related vein, scholar Youbin Kang, in her essay “Exorcising the Haunted Desire for Legibility”, contends that Cha’s fascination with martyrs suggests that death becomes one means by which the marginalised seek legibility. As Kang writes, “Cha’s ghosts are summoned for the purpose of exorcism and transcending trauma. Dictee should be considered among the lineage of literature by marginalized women who reckon with ghosts through a spiritual and ritualistic guide for how to live on.”

}

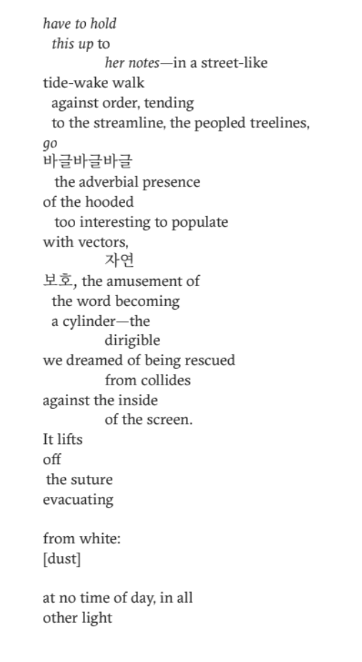

Many of the pieces discussed above take Cha’s body of work as a point of departure, sometimes as an object of sustained analysis, and at other times interwoven with personal reflections on the impact of encountering her writing. Contributors think through questions of deleterious labour conditions under South Korean economic development, or the history of Korean partition and the generational griefs that followed. Others move from Cha towards experiments that are either primarily personal or explicitly provisional. Translator Wirunwan Victoria Pitaktong does not mention Cha directly in her contribution, but instead offers a meditative reflection on her Thai father’s idealisation of his life in America, describing these conversations as a “practice of translation”, ruminating “in the suspended space between languages, and embodying them in other words”. Valentina Jager, a Mexican American translator, presents excerpts from her ongoing Spanish translation of Dictee, including handwritten annotations and reflections on how to render the interplay of English and French in Spanish. Poet Caterina Stamou contributes a poem moving between Greek and English, inspired by the multilingual indeterminacy of Dictee. Artist Jesse Chun’s piece “O” layers a still from Cha’s Mouth to Mouth, the letter O, the Korean character ㅇ, an image of the moon, a ring of women in hanbok, and a poem. Jed Munson’s poem “Two Lines / Arc” reads as a facsimile of Cha’s own fragmented, multilingual, and descriptive mode, evoking a presentation of Cha’s film-novel White Dust from Mongolia (1980):

Other essays can feel more tentative, containing compelling ideas and lines of inquiry without arriving at a clear resolution. Poet and scholar Jennifer Kwon Dobbs’s “Diseuse in a Dead Time: Letters to Theresa Hak Kyung Cha” takes the form of an epistolary poem, addressed deferentially to “Cha Seongsaengnim”, an honorific for teacher. Speaking from the position of a Korean adoptee in America, the piece intersperses handwritten notes from Korean language lessons, photographs of her family, traumatic recollections of sexual violence, and a series of fraught engagements with Cha’s work. One such instance involves a misreading of the French term “diseuse” as “disuse”, a misrecognition of the figure of the female artist who performs verbal monologues. This precedes a sequence on the French singer and actress Yvette Guilbert, accompanied by a photograph of her. Dobbs weaves together a narrative of Cha and Guilbert while thinking through the notion of illegibility in white space, although the piece ultimately concludes in irresolution. Cha appears as a beatific figure of understanding, one seemingly capable of containing the pains and complexities of such experience.

Writer and researcher Jennifer Gayoung Lee reflects on the impact of reading Dictee during high school, deriving from it a sense of kinship and comfort only years later, after beginning to learn the Korean language and Korean history, amid the protests surrounding the impeachment of former president Park Geun-hye in 2016. Lee problematises her acquisition of Korean through a programme funded by the United States Department of State, recognising the contradictions of doing so on an American passport, through American tax dollars, and in service of American national security interests. Perhaps it is because these pieces do not enter fully into the argumentative or discursive that their reflective qualities come to the fore, functioning instead as waymarks within processes of individual becoming.

Several contributions also seek to engage more overtly with Cha’s politics, rather than approaching them as implicit within her writing. A conversation between writer Teline Trần and organiser Yves Tong Nguyen centres on incidents of hate crimes against people of Asian descent in the United States, including Cha’s own murder. Tong Nguyen remarks that Cha “was never engaged in material struggle or collective action”, instead seeking engagement with liberal institutions, including “white people, academia, and art institutions at large”, rather than situating herself within the Asian American movement and its pursuit of collective liberation. Attempts to reposition her legacy within “discourse around liberation” coincided with the spike in Sinophobic violence following the COVID-19 pandemic.

Literary scholar Eunsong Kim connects Cha’s fluency in Greek and Roman mythology to the histories of chattel slavery and settler colonialism in the United States in her essay “She”. By demonstrating Cha’s familiarity with “foundational Western mythology”, Kim suggests that Cha’s text can be read as familial, while also drawing on the work of Page duBois to note that classics as a discipline was shaped by confederate generals “who looked to Greek society to justify the experience of slavery”. Kim thus outlines the limitations of allusion when read against American history, alongside additional tangents on Asian American ambivalence, the dismissal of Korea’s colonisation as definitional, the American origins of plastic surgery in Korea, and references to Deleuze, Guattari, and Spivak in thinking through minor literatures and modes of articulation.

Cha’s death has inexorably shaped her reception, producing resonances with past and present violence against Asians in the United States, even as her poetry, art, and film were not always explicitly oriented towards such concerns in themselves. Yet this contradiction remains, with Cha’s work having gained new currency within a climate of xenophobia in the United States, alongside a resurgence of mainstream interest prompted by the success of Minor Feelings (2020) by Cathy Park Hong and by initiatives such as Wendy’s Subway’s seminars and Evergreen Review’s commemorative portfolio The Muse: Dictee at 40 (2022). Cha has played a key role in my thinking on engagements with, and depictions of, Korean history, as well as on the dialogic encounters between the Korean-diasporic subject and different national, temporal, and geographic conditions. Cha’s life, writing, and art have continued to resonate beyond the temporal and material limits of her own life. The anthology concludes with the poem “On Stones” by Juwon Jun, which references the “lithic landscape” of Dictée’s cover:

Abstract is my noun, a violence done unto you, hardened by the cruel passing of time. Like your stones and the traces of mine. Yet, like all expressions, abstraction cannot forgo the material—it mourns its loss even louder through the obscuring.

Your stones move freely. Some days I envy their shape with a particular shame. Your children carry them too. Each day they scrape against our inners and soften their edges. They roll around and push through our skin, insist that we are porous. We no longer recognize the form. They polish and harden into a reminder. Only a reminder.

[…]

I write you as a reminder. I recite only these words:Let us be undone from this fantasy.

Let me be undone from theirs.

Let me be unrecognizable to this self.

Let these stones unmake this body.

Let these stones unmake them.

It is a fitting conclusion, one that in my mind captures and transforms a sense of Cha’s observational reflective style effectively, one conversant with ambiguity, indeterminacy, and contradiction, yet refusing their encumbrance.

How to cite: Chan, Jonathan. “Reading the Gap: Indeterminacy, Translation, and Legacy in She Follows No Progression.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 9 Feb. 2026, chajournal.com/2026/02/09/she follows.

Jonathan Chan is a writer, editor, and translator of poems and essays. His first collection of poems, going home (Landmark, 2022), was a finalist for the Singapore Literature Prize in 2024. His second collection is bright sorrow (Landmark, 2025). His forthcoming collection azalea dialogues (Gasher Press, 2027) is a recipient of the Two Languages Book Prize. He serves as Managing Editor of the poetry archive poetry.sg. His reviews and essays have been published in Quarterly Literary Review Singapore, SUSPECT, Soapberry Review, The Rumpus, and The Foundationalist. Educated at Cambridge and Yale, he was born in New York to a Malaysian father and South Korean mother. He was raised in Singapore, where he currently lives. More of his writing can be found at here. [All contributions by Jonathan Chan.]