茶 FIRST IMPRESSIONS

茶 REVIEW OF BOOKS & FILMS

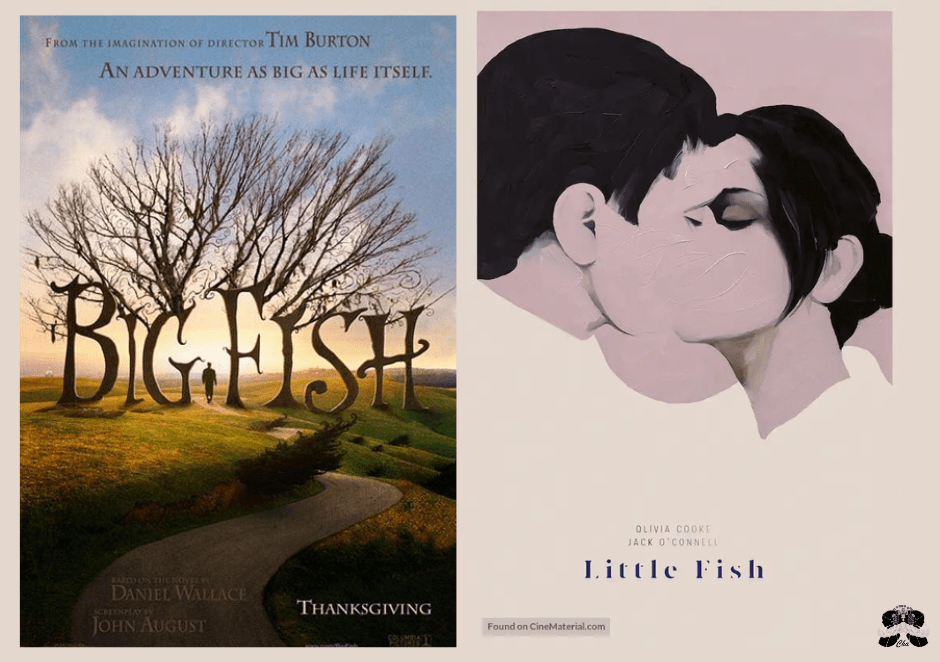

Editor’s note: Laurehl Onyx B. Cabiles considers the films Big Fish and Little Fish in relation to his father and the Filipino seafood dish kinilaw, using cinema as a lens for memory, grief, and continuity. Combining film criticism with memoir, his essay reflects on how stories sustain connection, transmit meaning, and endure beyond death, even as recollection weakens with time.

[ESSAY] “Big Fish, Little Fish, & The Fake Legend of Kinilaw” by Laurehl Onyx B. Cabiles

Tim Burton (director), Big Fish, 2003. 125 min.

Chad Hartigan (director), Little Fish, 2020. 100 min.

Whenever I need a respite from my responsibilities, I turn to the list of my favourite films in the Notes application on my phone. It usually takes a few minutes before I am able to decide which one to rewatch. I always choose the film that I feel will, at that particular moment, bring me comfort. One of the films on that list is Big Fish, directed by Tim Burton.

Like all of Burton’s films, Big Fish contains whimsical scenarios. What distinguishes this film, which follows the lives of a storyteller father, Edward Bloom, and his journalist son, Will Bloom, from Burton’s other works is its journey towards discovering truth within stories that may initially appear to be pure fantasy.

Edward Bloom is the kind of man who delights in telling his tales repeatedly. Although his son knows all of his stories by heart, he continues to question their authenticity. He feels that his father’s unbelievable anecdotes are the reason he never truly knew him. His scepticism is understandable, as his father’s stories involve giants, a werewolf, a witch with a glass eye that can reveal one’s death, a hidden town, and other illogical and inconsistent tales.

Big Fish reminds me of my father, which may explain why I love it so deeply.

Big Fish reminds me of my father, which may explain why I love it so deeply. When I was a child, I would constantly pester him for a bedtime story, as I could not fall asleep without hearing one. I did not care whether they were real or fabricated. I simply loved his stories. He never tried to convince me to believe every word he spoke. It seems to me that what mattered most to him was to amuse me, and in that, he never failed.

)

There is one story that my father shared with me, which I still carry with me today. It concerns where and how kinilaw originated.

Kinilaw is a Filipino seafood dish with many variations, but it is commonly prepared using filleted raw fish, coconut vinegar, and various spices. I should also mention a few details that are essential to the legend. Kinilaw is pronounced as kee-nee-laow ([kɪˈnɪlaʊ]). My father’s name is Lauro, and the “lau” in Lauro sounds like the “law” in kinilaw.

The legend he once passed on to me took place long before I was born. According to my father, he worked as a cobbler in Polomolok, South Cotabato, alongside other employees at the time. His boss, who was Bisaya, would often instruct him to complete tasks beyond his specified role. The pay was modest, but since food and lodging were provided free of charge, it was sufficient for him.

One evening, after working late, he was tasked with preparing dinner. His co-workers informed him that their boss was hungry and irritable, so he needed to cook quickly. When he checked the refrigerator, he found that the ingredients were limited. There were only fresh tuna, coconut vinegar, onions, ginger, and chillies. As he struggled to decide what to prepare, he heard his boss shouting from the living room, asking whether the food was ready.

In a moment of panic, my father cut the fish into cubes and placed them in a bowl.

In a moment of panic, my father cut the fish into cubes and placed them in a bowl. He then sliced the spices and added them to the main ingredient. At that point, he had no idea what he was making. He simply continued with what he had begun. He poured the coconut vinegar into the bowl and mixed everything together. Before serving the dish, which he did not even know how to name, he prayed that he would not be dismissed.

During dinner, his workmates feared for him, as none of them knew what kind of dish he had placed on the table. Their boss was the first to take a bite. For a few seconds, no one uttered a single word. All of them awaited his reaction. He took another mouthful before saying, “Kini, Lau, lami kaayo! (This is very delicious, Lau!)”. When my father was asked about the name of the dish, he replied, “Kini, Lau”, instantly and without much thought. As time passed, the name “Kini, Lau” eventually became “Kinilaw”. That was how kinilaw came to be.

Of course, my father did not invent kinilaw. According to Tikim: Essays on Philippine Food and Culture (2020), written by the late cultural historian Doreen Fernandez, kinilaw existed long before the Spaniards reached Philippine shores. The book also notes that the 1913 dictionary of Pedro San Buenaventura documented kinilaw as “adobo de los naturales” (the adobo of the natives). This indicates that kinilaw is a long-standing traditional method of cooking that predates foreign influence. Regardless of the authenticity of the fabricated legend, I still cherish it. After all, it was one of the reasons I learned to love stories.

On his hospital bed, Edward Bloom in Big Fish implored his son to narrate how his story should end. Will Bloom began by telling his father that they escaped the hospital together. They entered a car and drove to the river. When they arrived, everyone from one of Edward’s stories was there. Each character was happy to see Edward bid his farewell and transform into a very big fish. From that moment on, Edward became a story, and Will inherited the role of the storyteller.

At Edward’s burial, Will discovered that all of his father’s tales were embellished truths. From then on, despite the blurred line between fiction and reality, he understood what kind of life his father had lived.

The time I have spent remembering his stories is longer than the time we shared together.

When my father died, I was not by his side. I cannot recall where I was. I was eleven at the time. My sister was six, and my brother was four. What I remember clearly is the final night of his wake. People who knew him from different places were present. I stood before them to deliver a eulogy I had written on a crumpled piece of paper. I was meant to share a humorous story about my father, following the script. However, I became tongue-tied, and my hands shook uncontrollably. As soon as I realised that I would cry if I continued, I ended the speech abruptly. I could not face the audience as I left the stage, and I hid until dawn.

It has been almost fifteen years since his death. I am now twenty-six years old. The time I have spent remembering his stories is longer than the time we shared together.

)

Last year, I discovered the film Little Fish. It has no connection to Big Fish, despite the similarity in their titles. Little Fish is a science-fiction drama directed by Chad Hartigan. The film centres on the relationship of a young married couple, Emma and Jude, who strive to maintain their bond amid the outbreak of a widespread virus that causes memory loss, known as the NIA (Neuro-Inflammatory Affliction).

The protagonists’ love story begins in a familiar way. They go on dates and attend parties until they realise that they love each other deeply. During one of their simple outings, when they visit a pet shop surrounded by aquariums, Jude asks Emma to marry him. As it was not part of his plan, he admits that he did not bring a ring. Emma still accepts the proposal and asks Jude to buy her a fish instead. They commemorate that moment by getting identical tattoos of a little fish on their ankles.

In the early years of their marriage, Emma often hears distant news stories about a fisherman who forgot how to steer his boat and a woman running a marathon who could not remember to stop. These incidents intrigue her until a pilot forgets how to fly a plane. From then on, the fear of contracting the disease lingers in her mind.

Emma’s fear draws closer when their close friend Ben, whose girlfriend Samantha is also their friend, becomes infected with the NIA. The disease completely overtakes Ben’s mental state until he can no longer recognise Samantha, to the point where he believes she is an intruder.

Eventually, Jude contracts the NIA as well. In an effort to preserve their shared history, Emma writes down the important details of their lives. She also uses Polaroid photographs, with notes written on the back, to help Jude recall the significant moments of their relationship.

)

From time to time, my siblings would ask about my father, as they had little to no memory of him, and I would do my best to explain what kind of man he was. I would even recount some of his stories, yet I always failed to recreate the voices and gestures he once used.

When I began to feel that my memories of my father were slowly fading, slipping away as I tried to hold on to them, I started to write about him. The urge to turn our past into poems or essays emerged as I sifted through the moments we had shared and realised that I could no longer clearly recall his voice or his face.

Since Little Fish is not an Adam Sandler film, Emma becomes infected as well. Before the memory-erasing virus completely overtakes them, she and Jude go on a road trip to escape the terror of the pandemic. In a sense, this journey also serves as a way for them to create new memories that they might cherish. Unfortunately, by the end of the film, they become strangers to each other once more.

)

I will be reminded to smile and to remember my father’s fabricated legend.

Ever since I watched Little Fish, I have been unable to stop myself from connecting it with Big Fish. The reason lies in my fear of losing what remains of my father. I associate Big Fish with remembering him, and Little Fish with forgetting fragments of him.

There is a quote in Big Fish that I deeply love: “Have you ever heard a joke so many times you’ve forgotten why it’s funny? And then you hear it again, and suddenly it’s new. You remember why you loved it in the first place.” I hope that whenever I see kinilaw, I will be reminded to smile and to remember my father’s fabricated legend.

How to cite: Caibles, Laurehl Onyx B. “Big Fish, Little Fish, & The Fake Legend of Kinilaw.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 4 Feb. 2026. chajournal.com/2026/02/04/kinilaw.

Laurehl Onyx B. Cabiles is a writer from Cotabato Province. He holds a Bachelor of Arts degree in English Language. He has been a fellow in several writing workshops in Mindanao. His work has appeared inBangsamoro Literary Review, Ultramarine Literary Review, SunStar Davao, and Dagmay. [All contributions by Laurehl Onyx B. Cabiles.]