Editor’s note: Zheng Wang’s essay reflects on his encounter with the poet Zhang Zhihao and the process of translating his poetry across languages and generations. It traces their meeting by the Yangtze River into a broader meditation on rootedness, memory, and the ethical labour of attention to both place and person. Writing as a translator shaped by Wuhan and distanced from it, Wang considers Zhang’s poetics of radical simplicity and their quiet resistance to erasure, abstraction, and spectacle. Translation becomes an act of listening, restoration, and passage. A selection of these translations can be found HERE.

[ESSAY] “A Gaze Across the River: On Translating Zhang Zhihao” by Zheng Wang

On the evening of 10 December 2025, on the wuthering riverbank of Wuchang, the Yangtze flowed past, ochre and silent in the winter dusk, carrying within its currents the sediment of centuries and the uneasy, immediate memories of recent years. I was waiting to meet Zhang Zhihao, a poet whose work I had come to translate, in a city that is not my birthplace but one where I came of age, a hometown etched deeply into my personal geography.

We met in a bustling, smoky barbecue restaurant overlooking the water. The setting felt apt: mundane, unceremonious, and deeply rooted in the local qi of Wuhan. When he arrived, Zhang Zhihao (pictured left) was more approachable than his official photographs suggested, his demeanour marked by a gentle, watchful calm. What struck me most was not the titles he carries, Vice Chair of the Hubei Writers’ Association and recipient of the Lu Xun Literature Prize, but his unassuming generosity and his attentive interest in the work of younger writers like myself and the poet Li Liuyang, who had first connected us. In that moment, over simple food by the mighty river, the abstract figure of “the poet from Wuhan” dissolved into a real person: a man who has spent a lifetime observing, remembering, and forging language from the clay of lived experience.

I came to Zhang Zhihao’s poetry through a circuitous route, one that speaks to my own disjointed relationship with contemporary Chinese letters. It was the poet Li Liuyang who first urged me to read him. I confess to a certain sense of belatedness, even of shame: though Wuhan is a city I claim as a formative hometown, my understanding of its literary pulse was faint. Immersed in other academic and artistic currents, I had remained a stranger to the very voices shaping its cultural consciousness. Li Liuyang’s recommendation was a corrective.

Upon reading Zhang’s work, I was struck by a quality that felt both foundational and radical: a poetics of radical simplicity (zhipu) that never slips into naïveté, but instead carries within its clear diction a profound, often quietly critical, gravity. His poems are deceptively straightforward, about wildflowers, a sleeping father, a dripping pickled fish, hills, yet they serve as vessels for complex emotional weather: grief, tenderness, endurance, and a deep, unresolved dialogue between the rural past and the urban present.

This meeting by the river clarified a silent conversation already unfolding through my translations. Zhang Zhihao represents a crucial generational arc in Chinese poetry: the trajectory from village to city, from agrarian rhythm to the dislocations of industrial and post-industrial life, from the margins to the contested centre. His poems are archives of this passage. They are dense with the smell of earth, the weight of parental silhouettes at dusk, and the ghosts of buried potatoes and rusted hoes. There is a profound sense of rootedness, even when that root is one of loss or remembrance.

My own generation, by contrast, often moves within a different existential geometry. We are frequently unmoored, “rootless” in a neutral sense, navigating a world in which coordinates are no longer fixed by a single plot of land or an uninterrupted lineage. We traverse globalised spaces, digital realms, and hybrid identities. Sitting across from Zhang, I felt the weight of his rooted lineage and the expansive, sometimes formless, horizon of my own.

Yet his encouragement was not a call to return to a fixed point, but an invitation to journey further. He seemed to hope that our generation might extend his line, a segment drawn from village to city, from memory to present, into a new plane, a broader zeitgeist. Not to erase the past, but to transform its linear narrative into a multidimensional field of inquiry. His poetry, in its steadfast attention to the local and the intimate, paradoxically opens onto this universal plane. The “wildflowers on the plateau” are specific to a Chinese landscape, yet their offering, “I am willing to be someone / who will never grow bitter at the world”, is a translatable manifesto of fragile resilience.

This brings me to the other, inescapable layer of this project: Wuhan itself. Since 2020, the city has been subjected to a global projection of panic, reduced to a symbol, an epicentre, a “sticky object” of fear, as Sara Ahmed might put it. Its complex, vibrant, gritty human reality was overwritten by a monolithic narrative. Translating Zhang Zhihao became, for me, a deliberate act of literary restoration. It is an attempt to return to the world a Wuhan that is not a headline, but a living texture, a city of rivers and hills, of smoky barbecues and quiet domestic rituals, of unspoken histories and personal mourning. His poem “If Roots Could Speak” is a quiet anthem against erasure: “If roots could speak, / they would say the underground / is better than the ground. // My dead mother / is still alive. / This year, she turns eleven.” This is not a poetry of grand statements about collective trauma, but one of intimate, subterranean persistence. It reveals, evaluates, and mourns from within the granular details of a life, and thus, by extension, of a place.

The act of translation, then, is my way of joining this quiet labour. It is a crossing over, like the “earthworm crossing a lonely grave” that needs “half a lifetime”, from one linguistic shore to another. I strive not for lexical precision alone, but to carry across the river that specific emotional weather, the weight of the father’s bony feet, the lightness of the fish-scale-covered coat after dusk, the “open arms” of the hills waiting. It is an act of faith: that a particular love for a 丘陵 (qiuling, hill) in Hubei can resonate as a “Love of the Hills” anywhere; that the “Terminator” of a private love affair can speak to endings and continuities everywhere.

Meeting Zhang Zhihao by the Yangtze confirmed that this work is not merely textual, but human. It is about listening to the roots beneath a globalised city, and helping, in my small way, their speech to travel. His poems, and the city from which they are inextricable, deserve to be known in their full, quiet, complicated humanity. I hope these translations can offer a glimpse of that world, one in which grief and beauty drip with the slow, deliberate patience of a pickled fish in the sun, gathering “the last bit of strength” before night falls.

)

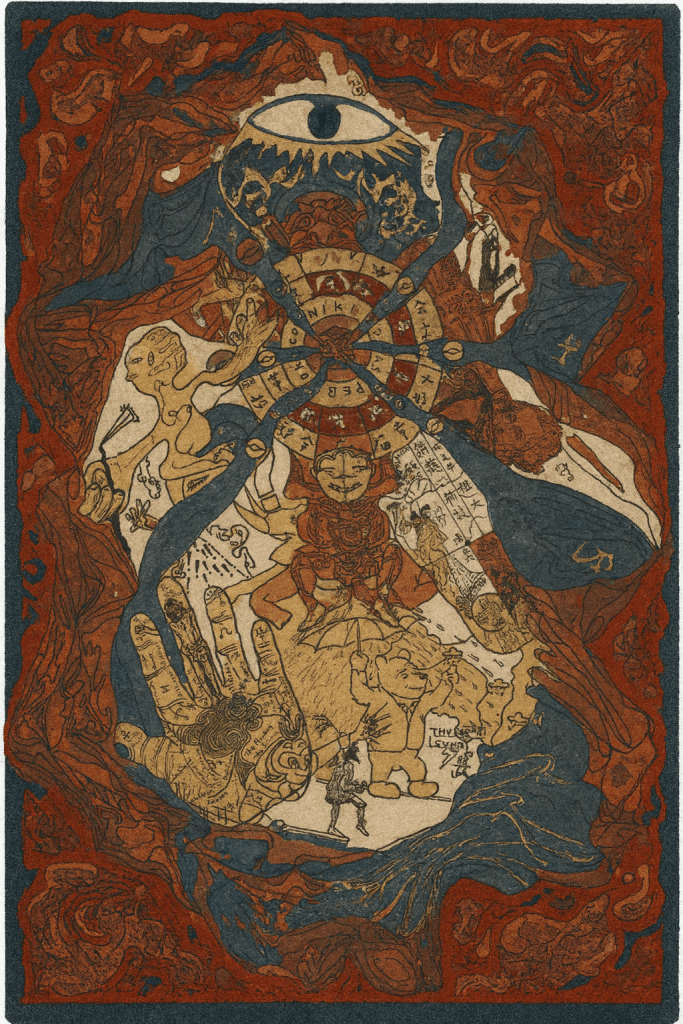

Art pieces by Zheng Wang related to the Covid and Wuhan memories:

Virus Body, 2020

January Dream Series, 2020

How to cite: Wang, Zheng. “A Gaze Across the River: On Translating Zhang Zhihao.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 22 Jan. 2026. chajournal.com/2026/01/22/zhang-zhihao.

Zheng (Moham) Wang, originally from Wuhan and of Yao (Iu-Mien) ethnicity, currently resides in Singapore. A member of the Independent Chinese PEN Centre, he was awarded the Wang Guozhen Poetry Prize in 2020, the Taiwanese “Fourth Luo Ye Literary Award” for fiction in 2023, the Singapore “Xinhua Youth Literary Award” for poetry, and the 2024 Lianhe Zaobao Gold Prize (Fiction Category), among others. His poetry and fiction have appeared in Qingdao Literature, Youth, Young Writers, Taiwan’s Taike Poetry, Vineyard, China Daily, Liberty Times, and Hong Kong’s Voice & Verse, P-Articles, and Hong Kong Literature. His English-language poetry has been featured in Queer Southeast Asia, Malaysia Indie Fiction, Woman, Cha, and Voice & Verse Poetry Magazine, among others. His poetry and illustrations were also selected for the 2023 Chengdu Biennale parallel exhibition “Perceiving Geography.” He holds a BA in Studio Art and Art History from Rice University (USA), an MA in Aesthetics and Politics from the California Institute of the Arts, and is currently pursuing a fully funded PhD in Art, Design and Media at Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. More at mohamstudio.com. [All contributions by Zheng Wang.]