Editor’s note: In his latest essay for Cha, Daniel Gauss examines Dafen, a former rural settlement located in Shenzhen’s Longgang District in southern China, within the Pearl River Delta near the Hong Kong border. The essay examines Dafen’s transformation from village into a global oil-painting factory shaped by Western decorative demand and Shenzhen’s export-oriented production logic. After the 2008 crisis, copy production waned, giving way to tourism and curated creativity. Dafen evolved into a post-industrial lifestyle district organised around consumption and spectacle.

[ESSAY] “Dafen Transformed: From Painting Factory to Pre-Fab Cool Zone” by Daniel Gauss

Shenzhen is often cited as one of the most successful experiments of China’s post-1978 economic reform era: a city created from scratch and transformed into a global hub of manufacturing, technology and finance.

The city’s development, however, contradicts a familiar Western expectation that rising wealth will automatically give rise to a corresponding flowering of experimental art. That may form part of Shenzhen’s future, but for now there is a lesson to be learned from Dafen.

Before 1989, Dafen was a small, rural Hakka village. It consisted largely of farmland, with only a few hundred residents engaged in rice cultivation and other forms of local labour. China’s reform and opening, together with the establishment of Shenzhen’s Special Economic Zone, brought massive industrial growth to the surrounding area. Dafen, located just outside the original SEZ boundary, offered inexpensive land and labour, which made it attractive to production-oriented businesses.

In 1989, a Hong Kong art dealer named Huang Jiang moved there. Already involved in the regional oil-painting trade, he recognised an opportunity to use local labour and low costs to produce paintings for international buyers. He established a large workshop in Dafen and brought painters with him. This initiative laid the foundation for the local oil-painting industry that continues to this day.

During the early 1990s, more artists and dealers arrived, drawn by the viability of the business model. Demand in Europe and North America for affordable, hand-painted artworks had already been substantial by the late 1980s. Huang identified this demand and understood that Chinese technical skill and low production costs could satisfy it. Proximity to Hong Kong, together with Shenzhen’s rapidly improving infrastructure, made it feasible to receive orders and ship paintings internationally.

Inexpensive living and working space, combined with low labour costs, made mass production possible in Dafen. Once Huang’s workshop proved successful, other painters and dealers followed, seeking to capitalise on existing workloads and orders. A production-line workflow soon emerged, in which different specialists painted different sections of a canvas in a production-line manner, accelerating output while maintaining consistent quality.

Throughout the 1990s and 2000s, Dafen evolved into a dense cluster of workshops, galleries and art suppliers. Many thousands of painters produced copies and decorative works for export, transforming Dafen’s economy from that of a poor village into an internationally recognised decorative art-production hub.

This transformation was enabled by the rapid growth of middle-class home ownership during the 1980s, along with the expansion of suburban housing, hotels, offices and restaurants. Such spaces required wall décor that appeared refined but remained affordable. A framed oil painting signalled taste and status in a way that posters or prints could not. Within Western visual culture, “oil on canvas” historically implied craftsmanship, seriousness and cultural capital.

Most Western buyers were unconcerned with authorship; what mattered was that the work looked like real art. Hand-painted copies fulfilled this symbolic function at low cost. Importers already sourcing furniture, textiles and decorative goods from Asia realised that paintings could be treated as another category of décor. Moreover, Shenzhen and Hong Kong logistics made shipping straightforward. Paintings were lightweight, high-margin and resistant to damage, which made them ideal commodities.

Buyers often favoured recognisable imagery: Van Gogh’s sunflowers, Monet’s water lilies, or generic European landscapes. These works were not perceived as forgeries but as decorative replicas. The governing moral framework was that of home décor rather than authorship. Western consumers sought a hand-made appearance, familiar imagery and an accessible price point.

Buyers often favoured recognisable imagery

Dafen made it possible to treat oil painting as a form of artisan manufacturing. The images being reproduced were already canonised through museums, textbooks and postcards, and copying them allowed that authority to be borrowed. Such works also lent themselves well to manual reproduction. Thick brushwork, visible strokes and strong colour contrasts concealed minor inaccuracies. Impressionism, in particular, tolerated variation and was therefore well suited to workshop-based production.

Old Master works were also in the public domain, eliminating the need for licensing and avoiding legal risk or royalty payments. This was crucial for large-scale export. Western decorative tastes tended to be conservative. Hotels, offices and suburban homes favoured landscapes, still lifes and figurative scenes. Old Master imagery complemented neutral interiors without provoking discomfort. In short, the Old Masters offered the safest means of converting art history into a decorative, saleable and lucrative product.

Once a site of intense image production integrated into global export markets, Dafen has since been refashioned into a sanitised cultural district, its surfaces transformed into glossy stages for cultural consumption. This shift is not accidental, nor is it a value judgement. It follows directly from Shenzhen’s founding logic and from the economic forces that reshaped Dafen after 2008.

Unlike Beijing or Shanghai, Shenzhen was not built upon layers of historical symbolic authority. Beijing carries political, historical and intellectual gravitas. Shanghai retains traces of colonial modernity and Western bourgeois cosmopolitanism. Shenzhen possessed neither.

It was conceived explicitly as an economic instrument, designed to attract foreign capital, absorb industrial risk and accelerate China’s integration into global markets. Its legitimacy derived from speed and output rather than memory or meaning. Culture was not postponed; it was structurally unnecessary during a period of urgency. Nevertheless, many people working in Shenzhen’s cultural sectors believe that it will emerge sooner or later.

In Western contexts, art has historically emerged alongside wealth because elites require symbolic distance from commerce. Money is converted into taste, refinement and intellectual or moral depth. Shenzhen never required such a conversion. Its wealth was new, unapologetic and nationally instrumental. Success in Shenzhen did not demand Western cultural camouflage. This reality shaped the kind of “art” that could rationally exist there.

Dafen Oil Painting Village emerged in the late 1980s as a direct response to global demand rather than local cultural ambition. By the mid-2000s, Dafen had become the world’s most concentrated site of hand-painted oil-painting production, specialising in copies of Western Old Masters and Impressionists.

At its peak before 2008, annual output was generally estimated at roughly ¥1-1.5 billion RMB, driven by exports to Europe and North America. Thousands of painters earned stable, often middle-class incomes producing decorative paintings. Authorship was irrelevant, while recognisability and speed were paramount.

This system functioned effectively because it aligned perfectly with its buyers. Western hotels, offices and suburban homes wanted objects that signalled “art” without requiring knowledge or risk. Artisan manufacturing became an extension of Shenzhen’s broader production ethos. Far from being regarded as a cultural failure, Dafen became an economic success precisely because it favoured market efficiency.

Problems first arose in 2008. The global financial crisis sharply reduced discretionary spending in Western markets, and decorative art was among the first expenses to be cut. Export orders collapsed. At the same time, high-quality digital canvas printing improved dramatically, offering cheaper substitutes that satisfied most buyers. Rising wages and rents in Shenzhen eroded Dafen’s original cost advantages, while decades of repetition exhausted the appeal of overused canonical imagery.

By around 2010, Dafen’s reported output value rebounded on paper to approximately ¥3-3.5 billion RMB, later stabilising in the ¥3-4 billion range throughout the 2010s and into the 2020s. These figures, however, obscure a fundamental shift. Export copy production was no longer the primary engine. Revenue increasingly came from domestic décor, online platforms, customisation, tourism and government-supported “creative industry” initiatives.

Dafen continued to generate income as a district economy, but it ceased to be a reliable source of livelihood for most painters. A small minority is now doing well, but many have struggled with low margins and irregular work. It was during this transitional period that some observers, including myself, believed Dafen might evolve into a “real art” village. I saw how exhibitions of work by Anish Kapoor or Maurizio Cattelan in Shenzhen drew art-hungry young people, and I believed that a modest bohemian community might emerge.

I visited Dafen before the pandemic with one of my Shenzhen high-school students who was preparing to study at the School of Visual Arts in New York. Conversations with vendors suggested that copy production might give way to original work and a more serious art culture.

The Dafen Museum, in particular, seemed promising. I enjoyed visiting the Dafen Museum because it presented gritty, substantive work by local artists. Much of the art addressed consumerism, IT culture, environmental damage and the working class of Shenzhen. There was often genuine humanity and sincerity in the work I encountered.

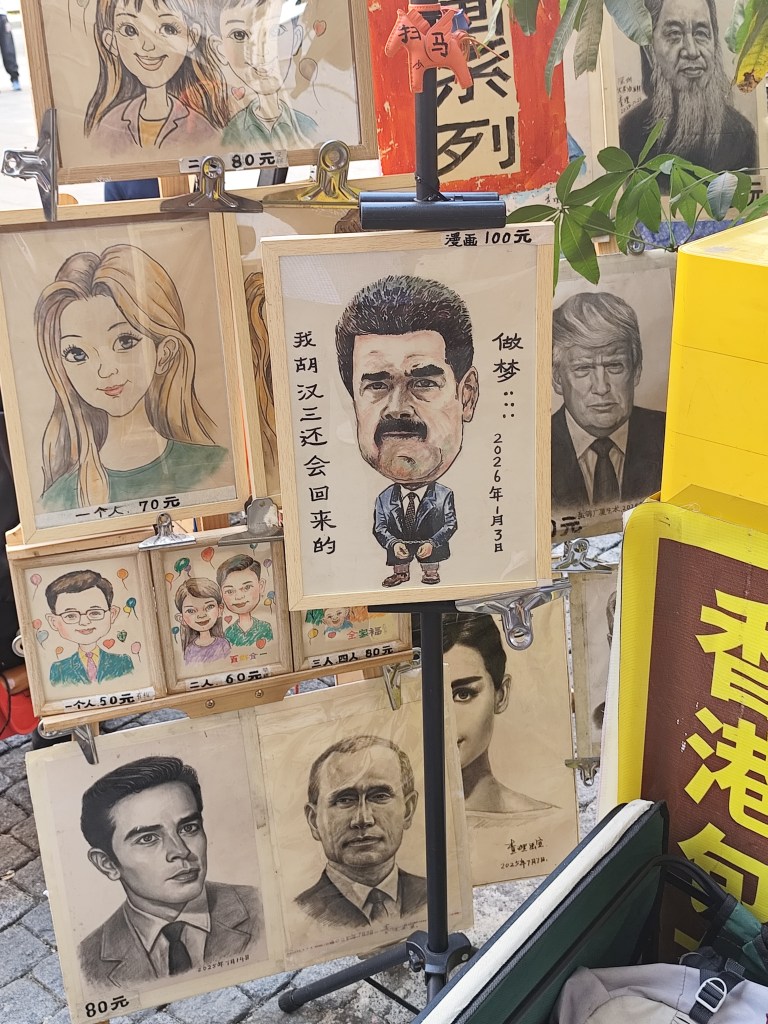

After two years away from Shenzhen, I now see something markedly different. Dafen has been thoroughly transformed into a managed cultural zone. The hutong-like grit has disappeared. In its place are newly built coffee shops aggressively soliciting customers, selling enough ¥20 cups of coffee to attempt to turn a profit. There are noodle restaurants, trinket stalls, decorative objects for apartments and a general atmosphere of lifestyle consumption aimed at “cool” urban youth.

The area has been sanitised, aestheticised and rendered legible. The transformation of the Dafen Museum is the most revealing. I now encounter an abundance of glossy abstraction, characterised by bright colours, polished surfaces and eye-catching compositions. There is also a prevalence of “cute” art. The work is technically competent and visually appealing, but it is perhaps what Duchamp might have called “retinal” art. Eye-popping art that provokes an internal “wow” based solely on initial visual impact.

Environmental concerns and working-class sympathy appear to have receded in many of the works, as far as I can tell, although a few traces remain. A deliberate choice seems to have been made to emphasise the upbeat and colourful at the expense of the subtle and speculative. What remains is art that photographs well and harmonises with cafés and foot traffic.

I do not wish to be judgemental. A preference for working-class or environmental themes is not universal. This shift should therefore not be understood as a betrayal of Dafen’s potential, but as its logical conclusion. Its role is now to aestheticise the district. Working-class themes disappear because their visibility conflicts with the narrative of leisure, creativity and consumption that the district now promotes.

The belief that affluence combined with time would yield cultural depth assumes a Western developmental sequence that Shenzhen was never meant to follow. This expectation was never applicable to Shenzhen and is almost antithetical to what the city represents. What Shenzhen produces instead is design, spectacle and experience, forms compatible with entrepreneurship.

Art, in the elite Western sense, requires ambiguity, the possibility of failure, misunderstanding and delayed recognition. It requires buyers willing to support risk and meaning rather than surfaces alone. Buyers do not create art, but they determine which forms of art can survive. Dafen’s buyers now want ambience. I did not expect this, but I should have.

Dafen did not fail to become a bohemian art village. It simply followed the logic of the city that surrounds it. It became exactly what a post-industrial creative district is designed to be, a demonstration of art redeployed as lifestyle infrastructure.

How to cite: Gauss, Daniel. “Dafen Transformed: From Painting Factory to Pre-Fab Cool Zone.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 20 Jan. 2026, chajournal.com/2026/01/20/dafen.

Daniel Gauss was born in Chicago and studied at UW–Madison and Columbia University. He has worked in the field of education for over twenty years and has published non-fiction in 3 Quarks Daily, The Good Men Project, Daily Philosophy and E: The Environmental Magazine, among other platforms. He has also published fiction and poetry. Daniel currently lives and teaches in China. See his writing portfolio for more information. [All contributions by Daniel Gauss.]