TIFF 2025

▞ 10. The Archivist’s Film: A Conversation on Kunsang Kyirong’s 100 Sunset

▞ 9. She Was Screaming into Silence: A Conversation on Cai Shangjun’s The Sun Rises On Us All

▞ 8. You Don’t Belong to Anyone: A Conversation on Kalainithan Kalaichelvan’s Karupy

▞ 7. The Paper Boy: On Park Chan-wook’s No Other Choice

▞ 6. Saigon Does Not Believe In Tears: On Leon Le’s Ky Nam Inn

▞ 5. The Need for Change: On Kei Ishikawa’s A Pale View of Hills

▞ 4. The Angel of Death: On Jafar Panahi’s It Was Just An Accident

▞ 3. Of Eros & Of Dust: On Ratchapoom Boonbunchachoke’s A Useful Ghost

▞ 2. Light At The End of the Labyrinth: On Genki Kawamura’s Exit 8

▞ 1. Affairs of the Heart: On Cai Shangjun’s The Sun Rises On Us All

Editor’s note: In this conversation, our resident film critic Nirris Nagendrarajah and Kunsang Kyirong, director of 100 Sunset, reflect on memory, belonging, and the quiet rhythms of Parkdale. Their dialogue moves through film, friendship, and the ways silence can speak. Kyirong shares how trust, archives, and observation shape her art, weaving tenderness into stories of diaspora. The conversation lingers on women, community, and the act of seeing, where a camera becomes both witness and voice, and ordinary streets hold something near to grace.

[TIFF 2025] “The Archivist’s Film: A Conversation on Kunsang Kyirong’s 100 Sunset” by Nirris Nagendrarajah & Kunsang Kyirong

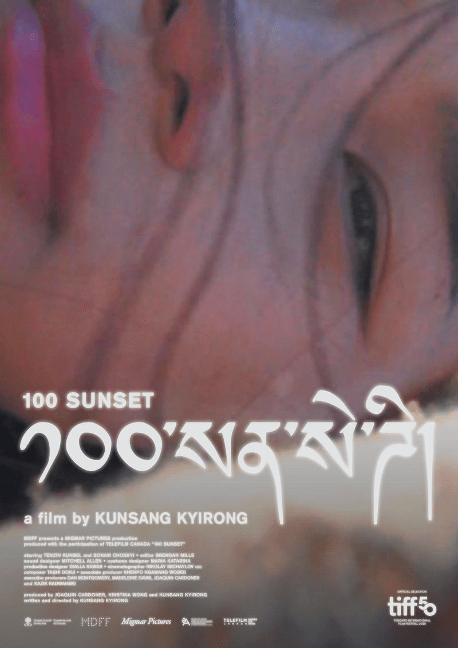

Kunsang Kyirong (director), 100 Sunset, 2025. 99 min.

INTRODUCTION

Nirris Nagendrarajah

A young woman looks out of the window, searching for something to stir her from her stupor. Her gaze meets that of another woman, who moves into the complex across the street, at the titular 100 Sunset, and she becomes fixated on her. Rather than merely observing her subject from a distance, the woman, Kunsel (played by Tensin Kunsel, in her debut role), feels an impulse to retrieve the camcorder we have seen her steal in the film’s hypnotic prologue, dazzlingly scored by composer Tashi Dorji. She presses record and begins to observe the other woman (Sonam Choekyi), zooming in as far as this man-made extension of the eye allows, documenting her object of fascination and identification, recording over and thus erasing the memories inscribed on the tape, which open the film: the memories, we later learn, a man captured of his wife, whom he will never see again.

“I like taking videos,” we hear him say from behind the camera.

That desire to make videos, to assert one’s personal perspective, artistic vision, and imaginative authority over the world, appears to infect Kunsel, a meek, taciturn protagonist whose encounter with this camcorder signals a period of growth. Filmmaker Kunsang Kyirong, in close collaboration with cinematographer Nikolay Michaylov and editor Brendan Mills, examines this transformation with a style entirely her own: attentive yet transgressive, abstract yet visceral. In the same way that there are two cameras and two protagonists operating within 100 Sunset, there are also two narrative threads, the other focusing on the Tibetan community in Parkdale, a neighbourhood in Toronto known as “Little Tibet,” and the process surrounding the initiation of a new round of a dhukuti, a rotating credit association, introducing the spectre of money into the fold.

Elliptical and dreamlike, 100 Sunset is a bold debut by Kyirong, one that refracts immigrant narratives through her innovative approach to form, elevating the work to the realm of the arthouse. When the opportunity arose to interview Kyirong during the Toronto International Film Festival, I knew that I had to ask her about the thinking that went into the film, what she feels her responsibility as a second-generation filmmaker is, and the influences behind 100 Sunset.

We met in a boardroom at the Sutton Place Hotel on a Tuesday afternoon.

A Conversation

on 100 Sunset

Nirris Nagendrarajah & Kunsang Kyirong

Nirris Nagendrarajah (NN): I read your essay “Asia Avenue,” where you give a brief yet beautiful account of your relationship with a region of Toronto known as Parkdale, which serves as the primary setting of 100 Sunset. “These adolescent memories of Parkdale are a mix of fall and summer, skimp, and hazy, held together by a few names, a giant silhouette of boys met online,” you write. At the film’s premiere, you spoke about Jameson Avenue and its importance to the film. Could you tell me a bit about what happened there?

Kunsang Kyirong (KK): Along with the secondary cast, I was living on Jameson during preproduction of this film. The two young women, the leads, would come and meet me at my apartment for a full year as we were preparing for production. That consisted of exploring the city, watching films, reading short stories, and improvisation. With the secondary cast, part of the meetings were with Khenpo Ngawang Woser, in his friend’s apartment on Jameson Avenue, where we would spend some time together, and also rehearse scenes.

NN: What were you hoping to achieve through those rehearsals?

KK: I think anticipating the production of the film and getting to know every individual in the cast a bit more, and hopefully building this sense of trust of our own kind.

NN: I thought the secondary plot was just as compelling as the first, the way it brushes up against it and almost inaugurates the film’s proceedings. It is a story about money, imbued with noir elements, and at the same time about immigration, which in itself feels like a genre, complete with its own archetypes and tropes. I know you have been careful to avoid being boxed in by Rear Window (1954) as a reference, but I was also reminded of Cindy Sherman and Brian De Palma.

KK: Body Double (1984) by Brian De Palm was a reference, for sure.

NN: Here, critically and crucially, you give the vision to a young woman. She possesses that wicked impulse to record. When did you first experience this impulse yourself?

KK: Growing up, I spent a lot of time going with my mum to where she grew up, this refugee settlement camp called Tezu in India, in Arunachal Pradesh. I was always very shy to take photos or record there because I never wanted to be an outsider. So I think asking this question, you know, when was the first time I picked up a camera? What I’m reminded of is not wanting to all the time because it creates this sense of distance from yourself. But later, because I would go so frequently in those spaces, that was when I really started developing a habit of taking photos.

NN: You spoke about the feeling of being constantly surveilled within the Tibetan community, which plays out in the film. Having grown up in a similar environment, I understood the sense that everyone is watching you, and that picking up a camera becomes a form of authorship, a way of reclaiming the story for yourself. You also mentioned how the two cameras in the film operate as a kind of double consciousness. I want to ask about your approach to the camcorder footage. What you do with it is quite striking; it is not merely an insert but a distinct voice within the film. You manipulate it and play with it, slowing it down, abstracting it, and speeding it up.

KK: A big inspiration early on was footage that a friend of mine showed me and said that I could use, which is integrated into the film during the opening sequence at Shangri-La, the restaurant, which is footage from her trip to Tibet in 2008 with her and her father. I was thinking about memories and mirroring that in the way that Kunsel then picks up the camera and records, and her own relationship to memories. An instinct that I had was making the experience between Gyatso’s character, whose camera it is, and Kunsel’s character hopefully very similar in their experiences, and having a device that could visually embody that.

NN: Without erasing another’s memory, Kunsel cannot write over her own, which I felt was quite a poetic and political act. What is it like to pay homage to your own people, but not in a way that ghettoises them? You are not talking about stinky food or how to pronounce a name, but rather taking a more artful approach to how we actually live our lives in these places, depicting the sublime within the suburbs. The way you think about that, both sensitively and artfully, feels really important. When people talk about representation, they often do so on a content level, but you have achieved something on a formal level, elevating it beyond what is usually expected.

KK: Honestly, I appreciate that a lot. I was very conscious of that early on when writing the script and also thinking about specifically Tibetan narratives that exist in the diaspora, which normally follow historical documentaries or emphasise Buddhism in a very explicit way. I wanted to offer a different perspective and think about the individuals who make up this fabric of the diaspora and this community, and have a bit of restraint when integrating aspects of plot into the film so that the two young women, their personalities, and their experiences are central, and the community exists as a sort of ambient background, even though there are activities that are very present and directly affect these two women’s lives.

NN: You mentioned earlier that you grew up shy. I think it is quite audacious to centre a film around such a silent figure, isn’t it? Yet her face is so striking that, as viewers, we are constantly reading it, searching for what she is doing and how she is thinking. She says very little, and she does not even tell Passang about the stolen dzi, an emblem, or that she probably should not wear it in public. I cannot think of a more compelling silent character to carry a film with her face.

KK: You know, when I first met Tenzin, she barely spoke as well. She had also recently immigrated; I think it was about six to eight months since she had newly immigrated when I met her, potentially even less. It took a while to get to know her. Her personality really helped render this already observant character and perhaps emphasise this silence or almost mute-like quality even more. A reference point for the film and the development of these characters is Catherine Breillat’s Fat Girl (2001), in these contrasts, this observance, and the sisterhood.

NN: Do you think of their relationship as one of sisterhood or twinship?

KK: Both, I think. Twinship in the sense that there’s a sort of mirroring happening between the two young women, as Kunsel fixates on Passang’s character, which we slowly engage with in the film. But a sisterhood in the way many of my own relationships within the community are, where you have so many cousins who are like sisters or friends who are like sisters. I think that’s a very real relationship that is depicted in the film.

NN: Speaking of influences, when I was at the premiere, the first question someone asked you was whether the film is autobiographical, which I found interesting. It was a white male audience member, which feels important to note. I think when you create something original, or something that feels different, there is often a desire to categorise it. It is as if people think: “this is too artful not to be referencing something else directly, but it must also be autobiographical in some way because we are second-generation creators.” Now that the film is out and you will be travelling with it, how does it feel to prepare yourself for that kind of reception? How do you navigate the divide between speaking to your own community and engaging with the mainstream?

KK: During the premiere, I had also mentioned that it’s not autobiographical. That’s not to say there aren’t observations and bits of me in the film, as any director, filmmaker, or writer would have. There are parts of you, you know. I also spent time with older people, playing cards throughout my childhood, but my experiences were very different. I didn’t immigrate; I was born in Canada. They’re very different from the experiences of this character. I wanted to emphasize that this film isn’t about me, but about a community that I’m from and that I’m also privy to. The film contains a set of observations and the accumulation of information and individuals I’ve met over the course of my life, but it also carries with it a perspective to a set of circumstances.

NN: Place seems to be important to you, as in your previous short Dhulpa (2022), where you enter a factory. There is this idea of place as somewhere one can enter but never fully become enmeshed within. I admire that your engagement with “place” is not merely as a backdrop. In a sense, 100 Sunset is a character in itself, yet it does not exist without the people who inhabit it. What is the next place your mind is inhabiting?

KK: So I’ve been working on Letters from Tibet, which was made for an exhibition at the Museum of Anthropology at UBC. The film is based on my research of Colonel Officer Eric Parker’s (1896–1988) archive. From this research I made a film that depicts an epistolary exchange between Parker, and a contemporary archivist. The film places Parker’s photographs from his time stationed in Tibet alongside clips from Frank Capra’s 1937 film Lost Horizon, which imagined a fictional utopia in the mountains of Tibet. The short film will be part of an exhibition from 20 November until March 2026, but I am also working on a festival cut. I’m also writing a new feature, which has been inspired by this archival research. So my head has been in the basement with these historical figures.

NN: When did you first develop this archival impulse? In 100 Sunset, you create your own archive in a sense, don’t you? What is it about archives that calls to you?

KK: I feel there is so much I don’t understand. In 2022, I went to London in the UK and spent time with the Tibetan archival collection at the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford. I wrote a short article based on Rabden Lepcha, an assistant photographer, and sifted through the materials, negatives, and photographs of Sir Charles Bell, who was documenting Tibet during the early twentieth century. I think that was when my first impulse towards this very specific form of archive began, and it has continued since. I’ve been thinking about films that have historically drawn from this same archive, or from literature. For example, Lost Horizon by James Hilton depicted Shangri-La for the first time, and his source material came from this larger archive of colonial officers who were stationed in Tibet. I’m not necessarily reanimating them, but studying the relationship between archival material and cultural production.

NN: But it requires a lot of faith, doesn’t it? Like when Kunsel sees Passang—you are observing something from a distance. It is as though you are dramatising that archival impulse, trying to grasp something that is there yet ultimately unattainable. And then she zooms in to the maximum, as far as she can. I feel that the film actually enacts what you are describing, the relationship between artist and archive in a way. What is your screenwriting process like?

KK: Normally, or at least for 100 Sunset, I write out scenes in a sort of stream of consciousness, and then I start to organise those scenes into an outline. Later, at times, I’ll rearrange them.

NN: Finally, a question drawn directly from the fFinally, a question drawn directly from the film: what is your favourite memory?

KK: My favourite memory of making this film—it’s hard to say because there were so many. The act of making the film and the general stamina from everyone during production is something that I hold really close to me. But one of my favourite moments was shooting on the train with the two young girls and giving them the camera, letting them run off and be a bit playful on their own with some direction, but sometimes just being inspired by their own momentum.

How to cite: Nagendrarajah, Nirris and Kunsang Kyirong. “The Archivist’s Film: A Conversation on Kunsang Kyirong’s 100 Sunset.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 25 Dec. 2025, chajournal.com/2025/12/25/100-sunset.

Nirris Nagendrarajah is a writer and culture critic from Toronto. In addition to Metatron Press, his work has appeared in MUBI Notebook, Little White Lies, The Film Stage, Ricepaper, Notch, Polyester, Intermission, Ludwigvan, and In the Mood Magazine. He is currently part of Neworld Theatre’s Page Turn program and at work on a novel. [All contributions by Nirris Nagendrarajah.]

Kunsang Kyirong is a Canadian artist and filmmaker. Her debut feature, 100 Sunset, had its world premiere at the 50th Toronto International Film Festival, where it received an honourable mention for the Best Canadian Discovery Award. Her films integrate documentary methods with fiction, often exploring the effects of immigration on culture and human relationships. She is currently in post-production on her film Letters from Tibet, which will be presented as part of an upcoming exhibition at the Museum of Anthropology at the University of British Columbia.