茶 FIRST IMPRESSIONS

茶 REVIEW OF BOOKS & FILMS

[REVIEW] “Anchors of Memory: Unhomely and Resilience in Jia Zhangke’s Still Life” by Hilda Wong

Click HERE to read all entries in Cha

on Jia Zhangke

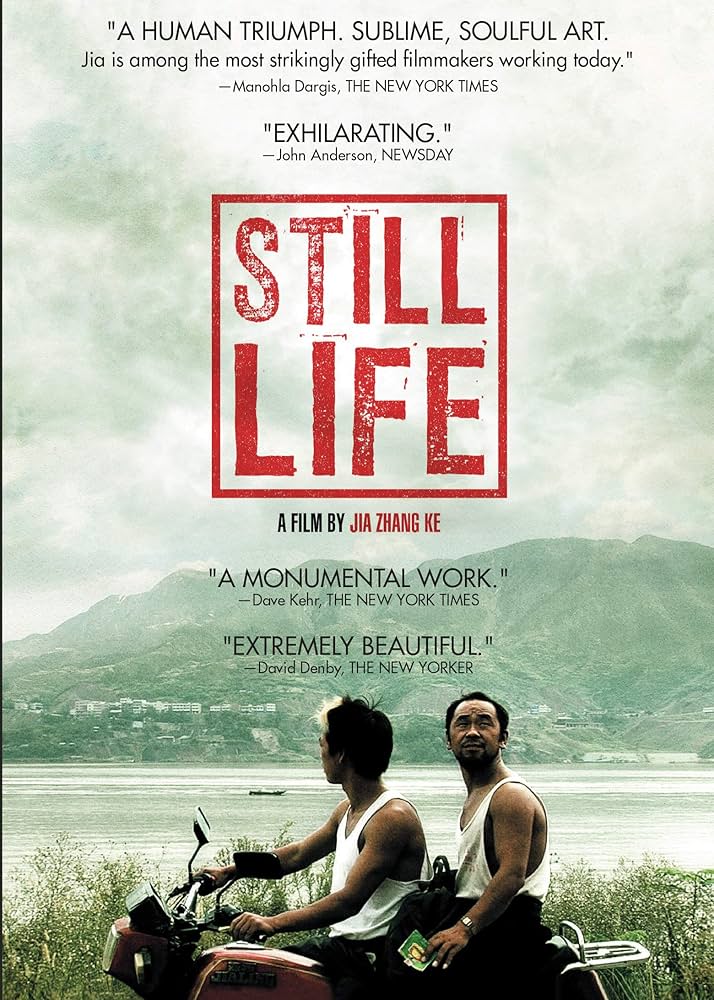

Jia Zhangke (director). Still Life, 2006. 108 min.

What “emotional anchors” would remain when the world itself is unmoored? A song, a teabag, an illustration on a dollar bill, a photograph, or a person? When we live in a world where all “anchors” can be easily lifted, how long would one hold on to them? This central, aching question is elevated in Jia Zhangke’s 2006 masterpiece, Still Life, a film that documents the parallel journeys of two displaced souls, whose search for lost spouses becomes a profound excavation of a vanishing world.

Still Life is a humanist documentary that profoundly and poetically captures the grassroots reality of one of the most dramatic modernisations in the history of China, the Three Gorges Dam. This cultural monument documents the colossal human cost of the instrumentalisation of cultural landscapes for collective use, which displaced over one million people and erased countless homes. Awarded the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival, the film is globally acclaimed for its intimate gaze and transformative aesthetic, offering a ground level perspective on grassroots experience under China’s relentless modernisation. By interweaving the trauma of two outsiders from Shanxi who search for their long lost spouses in Fengjie, the structural absence of “home” itself is unveiled. Through its unsettling blend of stark realism and the uncanny use of surrealist aesthetics, it emphasises grassroots perspectives on displacement and resilience, exploring how love and dignity are preserved through the dual acts of holding on and letting go.

Presented in Jia’s signature slow cinema style, the film unfolds through parallel, observational narratives in which the camera itself becomes a patient walker through ruins. This style frames resilience not as resistance, but as a silent navigation of an “unhomely” state. It opens with Han Sanming, who plays a fictionalised version of himself and travels to Fengjie to search for his long-lost wife and daughter. The second narrative follows Shen Hong, portrayed by Zhao Tao, who seeks her absent husband in Fengjie. Through a slow paced cinematic ethnography, the film captures ironies and sorrowful yet authentic portrayals, such as workers swinging hammers at the remnants of their own history, demolishing the place they once called home simply to earn a living. Similarly poignant is the despondent state of a landlord when he discovers the word “拆” (“demolish”) marked on his property without notice. Together, these grounded counter narratives serve as a form of cultural witness. They capture the displaced and the ordinary, whose experiences are often neglected in the brilliance and triumphalism of national history.

Han Sanming

Shen Hong, portrayed by Zhao Tao

Within this landscape of dissolution, the journeys of Han Sanming and Shen Hong extend beyond personal quests to reveal a deeper structural absence within families. Under China’s relentless modernisation, grand projects such as the Three Gorges Dam and the towering bridge under construction become agents of social dissolution. As a counter narrative to the triumph of modernisation, the film exposes the foundational loss of family structures alongside individuals’ sense of belonging. Enmeshed in a new town and a thriving economy, the characters illustrate how rapid development reshapes individual lives. The cost of “catching up with the times” is the abandonment of people, families and emotions. The protagonists’ condition of displacement and existential uncertainty amid rapid transition does not culminate in neat closure, but in melancholic acceptance, highlighting how the tide of progress washes away personal histories and connections.

The words “fluidity”, “rootless”, “nomadic” and “itinerant” defined my impression of Still Life. This depiction is not merely a state of being, but a pervasive collective psychological condition. Characters move endlessly with no place to settle, and this rootlessness, compounded by accelerated environmental transformation, infuses individuals with a sense of hopelessness. Han Sanming’s helpless gaze as he compares the Yangtze River to an illustration on his dollar bill, the only relic of his submerged hometown, captures how rapid change collapses time. The film presents a haunting metaphor towards its conclusion, when a barefoot tightrope walker traverses the gap between two doomed buildings. This image not only symbolises the itinerant movement of migrant workers, but also represents their precarious existence, with fate hanging by a thread. Han Sanming’s silent observation of the tightrope walker signals his readiness to face a future in the deadly coal mines. The workers’ determination and grit, fuelled by the “emotional anchors” they carry within, can thus be understood as a form of resilience. As Han Sanming’s friend Xiao Ma Ge says, “人在江湖,身不由己” (“Being in this world, one’s body is not their own”). At a deeper level, one does not always have a choice, and acceptance of obligation becomes a means of survival. This sentiment encapsulates the hopeless state of yielding to change as an inescapable force.

Beyond the film’s documentary power, Still Life is punctuated by moments of uncanny surrealism. A UFO glides silently across the sky; a building launches into space like a rocket, jarringly contrasting with the film’s prevailing mood. This technique is not merely a stylistic flourish, but a core philosophical argument. While these futuristic images are odd and unsettling, such lyrical ruptures visualise the displacement and disorientation of living through the erasure of home, security and structure. Their impracticality also stages a sense of unrealisable hope, mirroring the characters’ own attachment to unreachable ideals that attempt to fill the void left by lost “emotional anchors”.

A building launches into space like a rocket

If the film depicts the systematic submersion of landscapes, then the parallel journeys of Han Sanming and Shen Hong represent an internal exploration of loss conducted within that submerged world. Their quests, culminating in the dual dignities of holding on and letting go, become the film’s ultimate statement on resilience.

Han Sanming’s story is one of tragic loyalty, a conscious decision to hold on despite the systematic erasure of “emotional anchors”. He once bought a wife for 3,000 yuan; she left. Sixteen years later, with mutual consent, he offers 30,000 yuan of future labour to ransom her back. He seeks not merely a person, but the very concept of “home”. His journey poses a series of questions: how far would one go to reclaim an emotional anchor in a world where memory is the only remaining architecture? How far would one go for love? If love can be quantified, does its value lie in the sum, or in the sacrifice it represents? His dignity resides in his unwavering commitment, a choice to hold on even as the world around him releases its grip.

Conversely, Shen Hong’s path embodies the dignified art of letting go. Her confession of a “new lover” is revealed as a final act of self preservation. Is it a confession, or merely a claim? In her last effort to protect her dignity, she orchestrates her own closure. Why travel such a distance if not for love? She already carried the answer within her heart when her husband left her an incomplete phone number, yet she continued her journey in search of definitive proof. The answer she ultimately finds does not come from his evasions, but from the silent evidence of his new life that she witnesses. Her dignity lies in her acceptance, in choosing to move with the flow and release herself from a suspended past rather than be drowned by it. Together, Han Sanming and Shen Hong embody two fundamentally opposing responses to the film’s overwhelming transitions. Whether clinging to a disappearing past or relinquishing it to navigate an uncertain future, both assert a profound form of resistance and adaptation in a world where all other “anchors” have been lifted.

Ultimately, the film asserts that reality is not defined by false prosperity, but by the collective grassroots experience of those living in its shadow. It stands as a powerful counter narrative that captures the purest human desire for home amid the structural loss of family. The film reveals fluidity and adaptability within the Chinese spirit, not as cheerful resilience, but as a profound and sorrowful capacity to endure. This essential fluidity is embodied in both protagonists, in Han Sanming’s tenacious grasp of a disappearing past and in Shen Hong’s release towards an uncertain future.

How to cite: Wong, Hilda. “Anchors of Memory: Unhomely and Resilience in Jia Zhangke’s Still Life.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 16 Dec. 2025, chajournal.com/2025/12/16/still-life.

Hilda Wong is an undergraduate student in the Department of English Language and Literature at Hong Kong Baptist University, with wide-ranging interests in multicultural writing, speculative fiction, Modernist literature, and postmodern and postcolonial studies. [All contributions by Hilda Wong.]