茶 FIRST IMPRESSIONS

茶 REVIEW OF BOOKS & FILMS

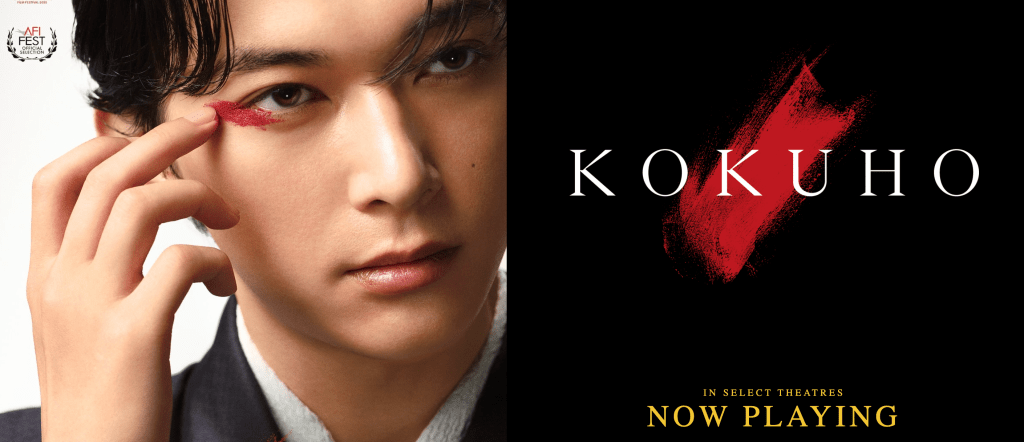

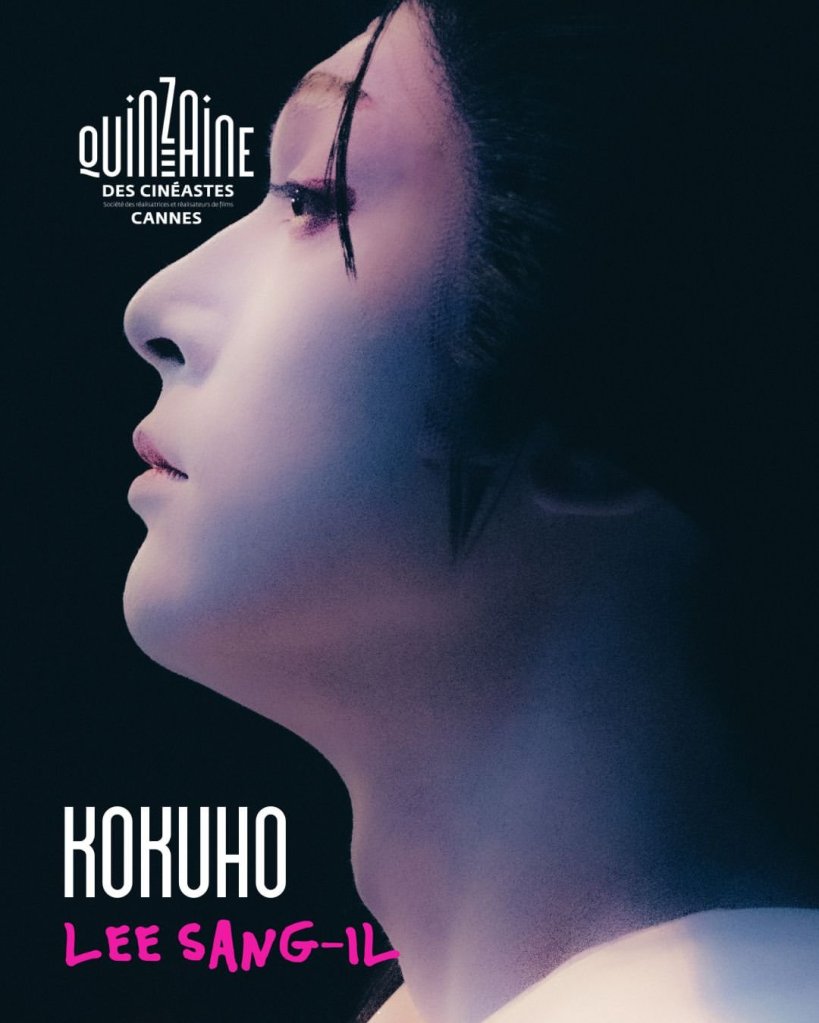

[REVIEW] “Kokuho: Lee Sang-il’s Mesmerizing Portrait of Kabuki Mastery” by Jennifer Eagleton

Lee Sang-il (director), Kokuho, 2025. 174 min.

What makes Lee Sang-il’s Kokuho special are the tight closeups of onnagata (men playing female roles in Kabuki) applying their thick makeup, and the widescreen long shots of Kabuki plays being performed, with their slow, stylised shoulder movements and inward-turned knees working in harmony as they glide across the stage. A story centred on the preservation of traditional ways, the problematic presence of outsiders, and the desire for perfection melds together to make a memorable film.

Reflecting on the film (which was adapted from Shūichi Yoshida’s novel Kokuhō), I think that the plays performed within it reveal much about the major protagonists. Helpful for audiences is the appearance of each play’s title at the bottom of the screen alongside a brief description. These plays mostly deal with unrequited love and death.

Famous Kabuki actor Hanai Hanjiro II visits a gathering held by the yakuza group Tachibana. During the gathering, Kikuo, the son of the Tachibana leader, performs an excerpt from the Kabuki play Barrier Gate with another yakuza youth.

Barrier Gate presents the story of Munesada’s lover Komachi, who on her way to Mii Temple for prayer is drawn to the barrier gate by the sound of his koto playing. The gatekeeper is suspicious of a beautiful woman travelling alone and questions her carefully. Munesada arrives, and the couple shed tears at their unexpected meeting.

I have only mentioned a portion of this story, but the film itself concerns an attempt to break through a cultural barrier, with mixed results by its end. Perhaps the choice of this play to open the film is therefore intentional.

Kikuo’s performance impresses Hanjiro, who requests to speak with him after the performance, but before this can happen a rival yakuza gang attacks, killing Kikuo’s father as Hanjiro and Kikuo watch. Encouraging Kikuo to embrace art over his criminal legacy, Hanjiro tells him that mastering Kabuki can be his “sweet revenge” after Kikuo fails to kill his father’s murderer.

The fifteen-year-old Kikuo becomes Hanjiro’s apprentice, despite the reluctance of Hanjiro’s wife Sachiko, who is wary of Kikuo’s yakuza background and lack of a Kabuki bloodline. Kikuo begins training alongside Shunsuke, Hanjiro’s son and the rightful heir to the family’s Kabuki legacy, and they become both friends and rivals.

The film revolves around this pair’s friendship and rivalry, the overarching importance of blood tradition in this ancient art form, and the desire to achieve perfection to the near exclusion of everything else, at least on Kikuo’s part. Kikuo is passionate and possesses an innate talent for Kabuki, whereas Shunsuke does not have such an intense drive. Outside costume and makeup, Kikuo is a rather cold and selfish figure, while Shunsuke shows more human emotions, getting drunk and maintaining a life outside Kabuki.

Hanjiro takes the pair to see a performance of Heron Maiden by Mangiku, a very old onnagata actor who is a Kokuho (a Living National Treasure). The performance deeply inspires both Kikuo and Shunsuke, but Mangiku warns Kikuo that although his face is beautiful, his ambition and lack of Kabuki background may also lead to his downfall.

Heron Maiden relates the tale of a woman consumed by passion and unrequited love who turns into a heron, leading to a tragic end in hell. This enigmatic piece, set on a snow-covered stage, conveys a range of emotions from stillness to joy, but is filled overall with sorrow.

I see this Kabuki play as a form of foreshadowing, for when Kikuo performs it years later, one senses the lonely price paid for overwhelming ambition in the pursuit of artistic perfection. Hanjiro decides to pair Kikuo and Shunsuke as an onnagata duo, making their debut in the play Wisteria Maidens.

Wisteria Maiden is a dance rather than a narrative piece, famous for its four kimono changes set against a vivid backdrop of mauve and purple wisteria flowers. The costume changes are performed on stage behind the trunk of a tree, as the maidens offer charming glances of love.

Kikuo and Shunsuke grow in popularity as performers, and all seems well. However, Hanjiro is suddenly involved in a traffic accident, is seriously injured, and becomes unable to perform the lead onnagata role in his upcoming production of The Love Suicides at Sonezaki. Contrary to everyone’s expectations, Hanjiro chooses not Shunsuke but Kikuo as his understudy, a decision that greatly displeases Hanjiro’s wife, Sachiko. Kikuo’s hand trembles as he attempts to complete his makeup before the performance, and Shunsuke must finish it for him as Kikuo laments that he has no Kabuki blood to protect him, unlike Shunsuke, who should have been given the role.

The Love Suicides at Sonezaki tells the tragic love story of a shop assistant and a courtesan, who are trapped by social norms and personal hardship. Their love leads them to commit shinju, or love suicide, as a desperate escape from their circumstances.

Despite his nervousness, Kikuo performs exceptionally well, upsetting Shunsuke, who leaves the theatre before the final curtain and then disappears for several years. This may foreshadow the problem of Kikuo’s status as an outsider in an art form that is inherently hierarchical. The play will be performed once more near the end of the film.

Hanjiro, later almost blind from diabetes, expresses his wish for Kikuo to inherit the title of Hanai Hanjiro III so that he may in turn inherit the title of Hanai Byakko IV and become head of the Kabuki clan. After Hanjiro’s death, Kikuo receives this unprecedented honour. He makes a wish at a shrine, promising to give the devil everything in exchange for becoming the greatest Kabuki actor in Japan.

Instead, the devil seems to signal a change in fortune upon Hanjiro’s death. Public resentment grows against Kikuo for “stealing” the Hanai Hanjiro name. His yakuza background becomes public knowledge, opinion turns against him, and major roles disappear. Shunsuke returns and takes what is seen as his “rightful place” in the Kabuki world as the true heir of the clan, despite his lack of practice during his missing years.

Mangiku, the Living National Treasure, advises Kikuo on how to regain access to elite Kabuki theatre. After a reconciliation with Shunsuke, the pair become popular once again, including in their performance of The Maiden at Dojoji Temple.

The Maiden at Dojoji Temple tells the story of a maiden who dances before a bell in the Dojoji temple and then reveals herself to be a serpent-demon. It is regarded as one of the most important pieces in the Kabuki dance repertoire, required of onnagata performers to demonstrate their mastery of classic dances.

The duo later appear together in The Love Suicides at Sonezaki, with Shunsuke in the male role. There is another especially touching performance in which their roles are reversed. Their fortunes continue to alternate. Kikuo performs Heron Maiden, echoing Mangiku’s famous interpretation, and the bittersweet nature of fame and its heavy cost becomes apparent.

Particular praise is due to the actors playing Kikuo and Shunsuke: Ryo Yoshizawa as the older Kikuo and Soya Kurokawa as the young Kikuo, and Ryusei Yokohama as the adult Shunsuke and Keitatsu Koshiyama as the young Shunsuke. They are entirely convincing in each of their roles.

Kokuho the highest grossing Japanese production to date in Japan, and Japan’s submission for the 2026 Academy Awards. Despite its almost three hour length, it is riveting throughout and has reinvigorated my interest in this traditional art form.

How to cite: Eagleton, Jennifer. “Kokuho: Lee Sang-il’s Mesmerizing Portrait of Kabuki Mastery.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 25 Nov. 2025, chajournal.blog/2025/11/25/kokuho.

Jennifer Eagleton, a Hong Kong resident since October 1997, is a close observer of Hong Kong society and politics. Jennifer has written for Hong Kong Free Press, Mekong Review, and Education about Asia. She has published two books on Hong Kong political discourse: Discursive Change in Hong Kong (Rowman & Littlefield, 2022) and Hong Kong’s Second Return to China, A Critical Discourse Study of the National Security Law and its Aftermath (Palgrave Macmillan, 2025). Her poetry has appeared in Voice & Verse Poetry Magazine, People, Pandemic & ####### (Verve Poetry Press, 2020), and Making Space: A Collection of Writing and Art (Cart Noodles Press, 2023). [All contributions by Jennifer Eagleton.]