茶 FIRST IMPRESSIONS

茶 REVIEW OF BOOKS & FILMS

[REVIEW] “Consequences of Cosmopolitan Dreams in Nawapol Thamrongrattanarit’s Human Resource” by Lorence Lozano

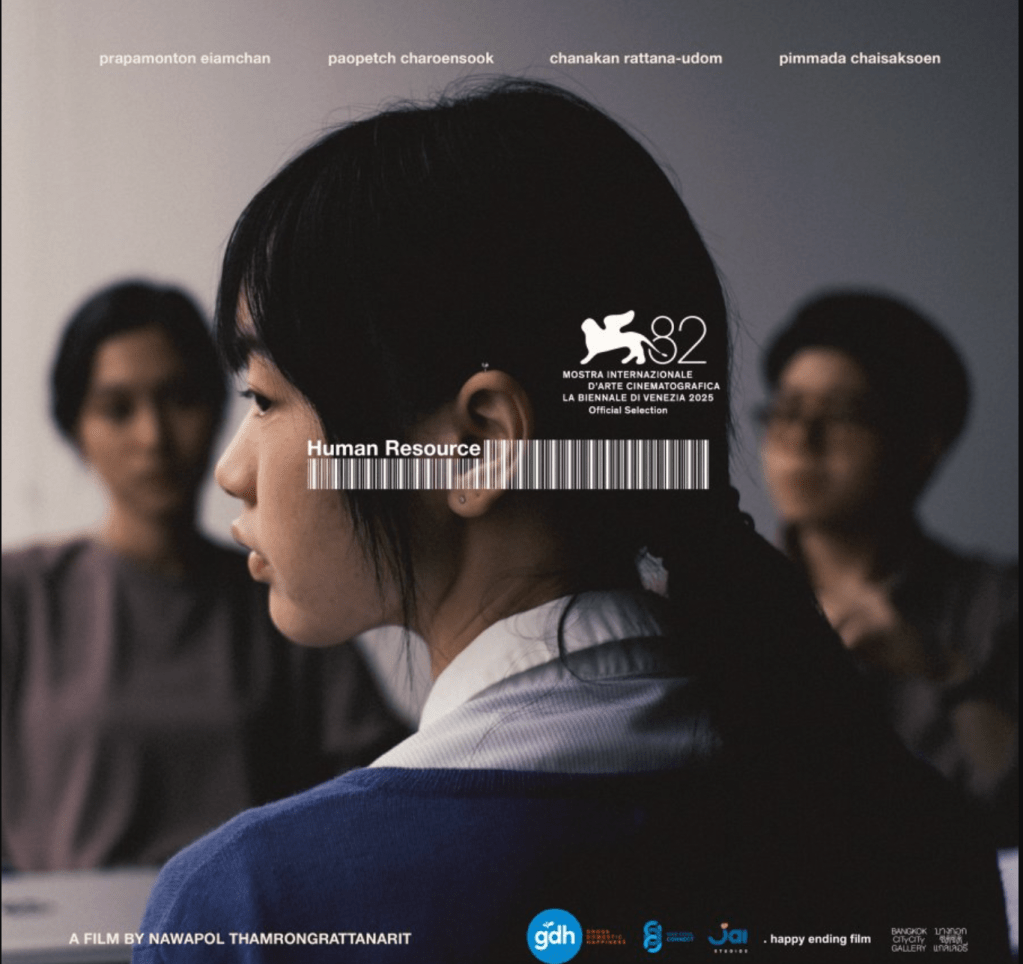

Nawapol Thamrongrattanarit (director), Human Resource, 2025.

Three years after his last film, Nawapol Thamrongrattanarit returns with a new work, Human Resource (2025), making the rounds at various festivals. It premiered before its first audiences at the 82nd Venice International Festival, where it received the Fondazione Fai Prize, followed by screenings at the 30th Busan International Film Festival and other prominent events, before finally reaching the Philippines through the 13th QCinema International Film Festival under the QCinema Selects programme.

As a counterpart to his 2017 film Die Tomorrow, which examines death, Human Resource explores the act of giving birth in an ever-changing society burdened by a failing economy.

The narrative centres on Fren (Prapamonton Eiamchan), a human resources manager who initially hides her pregnancy, grappling with the decision to keep it or have it aborted before the three-month limit set by Thai abortion law. In the opening, we see a womb X-ray before Fren is revealed to the audience. One detail I noticed, which the subtitle failed to capture, is how the doctor insists on her motherhood by addressing her not by her actual name but as “Mom.” Although she is only half-framed, we understand fully that she is not as ready as she appears. This happens twice, both times with the same woman doctor Fren consults. The incongruity between how the doctor addresses her and how she internally feels heightens the tension, as she is coerced without the agency to articulate whether she is prepared or capable. Once there is a sign of her pregnancy, she becomes bound by decree to carry it in accordance with the life system’s prescribed flow.

This dilemma arises not only from the doctor but also from her lover, Thame (Paopetch Charoensook), who makes decisions on her behalf and on behalf of the unborn child. He is already thinking ahead, subconsciously leaving Fren with no choice but to carry the pregnancy to term. The pressure intensifies when he suggests that they visit her mother to disclose the pregnancy. In these moments, we come to know Fren beyond her professional role. Her mother describes her as a people pleaser and weak, and now that she is becoming a mother, she is told she needs to be more forthright. Yet this advice offers no comfort; instead, she is overwhelmed by the growing pressure of raising a child she is unprepared for in a society that destroys its people.

Thamrongrattanarit captures these moments brilliantly with his ingenious director of photography, Natdanai Naksuwarn. Fren is consistently positioned in half-framed compositions, making it difficult to see her in full. She often appears with her back turned to the camera, as if refusing the audience’s gaze. While she is framed in this detached manner, Thamrongrattanarit reinforces the distance by depicting Fren as desensitised to everything unfolding around her, from the workplace to the life imposed upon her by a motherhood for which she is not ready.

This desensitisation becomes even more apparent when Jida (Pimmada Chaisaksoen) enters. We can observe a shift in the manner in which they conduct their interviews with the workers; they become more open to all questions, including those concerning the experiences one might encounter in a space where individuals are treated merely as commodities. Yet for Jida, this is nothing new, for she has long been accustomed to such treatment owing to the abuse she endured while working in her family’s noodle shop. To the capitalist, even those they know personally, even those who are family, are nothing more than units of labour who must work efficiently so as not to impede the business’s pursuit of success. As the saying goes, one can only imagine the abuse a woman faces in the workplace, particularly within a patriarchal society.

And Fren, as we have come to know her, detached from the broader masses of Thai society beneath the imagined cityscapes, is no different, for she is deprived of her own agency within the capitalist system in which she participates. Through this, people’s desires and dreams are commodified into mere products of an alien modernity, devoid of connection to the wider populace and stripped of any agency to conceive what alternative futures might be possible.

Disillusioned by the cosmopolitan dreams of a state striving to keep pace with globalisation while Thai society is driven towards self-destruction by its inability to sustain these imperial ambitions, Thamrongrattanarit exposes the consequences of hustle culture and the fascist-capitalist system that upholds it. He does so by depicting his characters as near-agents of the powers that dominate them, while simultaneously revealing the irony of a law that serves only the powerful, quietly corrupting his characters through the discomfort of witnessing them subconsciously benefit from that power.

Yet this discomfort arises not only from Fren’s passiveness, but from the manner in which Thamrongrattanarit shapes her agency within our consciousness, guided by our hope for some form of catharsis for Fren in a society that destroys her. She is rendered into near-nothingness, only faintly realised. Ultimately, we see her fully only as a reflection of a decaying, corrupted city on the verge of collapse.

How to cite: Lozano, Lorence. “Consequences of Cosmopolitan Dreams in Nawapol Thamrongrattanarit’s Human Resource.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 23 Nov. 2025, chajournal.com/2025/11/23/human-resource.

Lorence Lozano is a film critic based in the Philippines. They have contributed to various student short films as a script consultant. Their interests lie at the intersections of gender, politics, and temporalities within Southeast Asian cinema. [All contributions by Lorence Lozano.]