📁 RETURN TO FIRST IMPRESSIONS

📁 RETURN TO CHA REVIEW OF BOOKS AND FILMS

Click HERE to read all entries in Cha on Pillion & Box Hill.

Editor’s note: We are delighted to present Hongwei Bao’s essayistic film review, which blends cultural history, theory, and critique through the lens of Pillion (dir. Harry Lighton, 2025). The film is adapted from Adam Mars-Jones’s novel Box Hill, which Bao has also reviewed for Cha. In this essay, Bao explores the evolution of queer cinema, the intersections of sexuality and subculture, and the politics of representation. He situates the film within a wider genealogy of queer visual culture and traces the intertwined histories of gay biker, leather, and BDSM communities.

Harry Lighton (director), Pillion, 2025. 103 min.

Since the beginning of cinema as a cultural form, queer cinema has been a hallmark of radicalism, representing alternative genders, sexualities, and sexual politics. Much of this emerged as a critical response to the repressive social environments in which LGBTQIA+ people lived. Yet queer cinema has come a long way, as have queer rights. In 2025, same-sex marriage has been legalised in many parts of the Western world, and queerness has become an integral part of mainstream media and popular culture, evidenced by the global success of RuPaul’s Drag Race and the recurrent inclusion of same-sex couples’ dances in Strictly Come Dancing. One cannot help but ask: how else can queer culture be represented, and can contemporary queer cinema still embody radicalism?

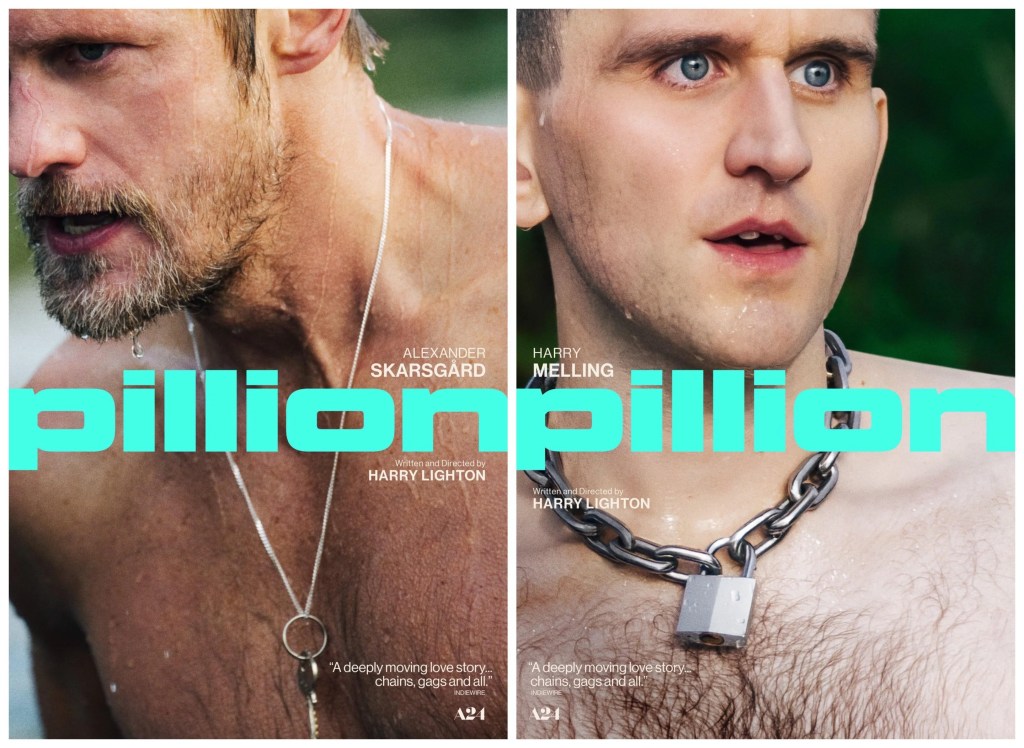

In this context, the directorial debut of British filmmaker Harry Lighton, his 2025 film Pillion, offers a fresh perspective. The film depicts radical queer love not by imagining the future but by revisiting the queer historical past. It tells the story of a queer romance set within a gay motorcycle club in 1970s Britain, centring on the relationship between a timid young man, Colin (Harry Melling), and a charismatic gay biker, Ray (Alexander Skarsgård). Their relationship is far from conventional. Colin provides all the services, domestic and sexual, that Ray demands, without expecting much in return. Their dynamic may be described as BDSM, even a total power exchange (TPE), between a submissive and a dominant.

In the history of cinema, such unconventional relationships have long existed within heterosexual romance, as in The Story of O (dir. Just Jaeckin, 1975), Secretary (dir. Steven Shainberg, 2002), and Fifty Shades of Grey (dir. Sam Taylor-Johnson, 2015). These films often conclude with the female protagonist “taming” the male protagonist, who presumably suffers from some form of childhood trauma or Oedipal complex, through her femininity and true love. His sadomasochistic desire is thereby “cured” as the pair enter a happy heterosexual union. Despite such narrative conventions, these films are usually sex-positive. It is worth noting that BDSM was a controversial topic in the feminist debates of the 1970s and 1980s. While radical feminists regarded BDSM as objectifying women’s bodies and perpetuating patriarchy, sex-positive, often queer, feminists celebrated polymorphous female sexuality and desire. Films featuring BDSM played an important role in these debates.

BDSM remains an important subcultural practice within queer culture. Here we encounter several interconnected terms encompassing both diverse sexual practices and multiple subcultural communities: gay, biker, leather, fetish, BDSM. These terms possess distinct yet sometimes overlapping histories. Not all bikers are gay, and not all gay men are into fetish or BDSM. It is the entanglement of these subcultural histories that is of particular interest here, as it relates directly to Pillion.

Motorcycle clubs have long provided a refuge for marginalised sexualities and practices, including gay, leather, fetish, and BDSM cultures. In the United States, as early as the 1930s, motorcycle clubs had already established the association between the black leather jacket and rebellion. The film The Wild One (dir. László Benedek, 1953), starring Marlon Brando, immortalised the leather-clad countercultural hero. After the Second World War, many American soldiers returned home from the front. The rising popularity of motorbikes offered them a way to maintain friendships and camaraderie, while also facilitating their pursuit of adventure and sexual freedom. The drawings of Tom of Finland became emblematic of post-war gay culture, capturing the emergence of a new form of gay masculinity that departed from the stereotype of effeminacy. Life magazine’s 1964 photographic essay, titled “Homosexuality in America” and featuring a group of leather-clad gay men at the Tool Box bar in San Francisco, was among the first mainstream depictions of gay life in American media. The article also famously described San Francisco as “The Gay Capital of America.”

In the 1950s, gay motorcycle clubs were founded in major American cities, including the Los Angeles based Satyrs Motorcycle Club and Oedipus Motorcycle Club. As many of the founding members were war veterans who valued order, hierarchy, and obedience, BDSM-centred sexual practices emerged within these spaces. Many of these clubs enforced strict dress and conduct codes derived from the military. New and junior members were expected to follow the orders of senior members, showing them due respect. Those who adhered rigorously to these rules became known as the “Old Guard”, while those who followed them less rigidly were termed the “New Guard”. (Their difference is dramatised in Pillion through two contrasting approaches to submissives within the Motorcycle Club.) The gay bikers were also sexual outlaws and social non-conformists. Many rejected middle-class, heteronormative social and sexual norms, refusing marriage and romantic relationships at a time when same-sex marriage was unimaginable. In Pillion, Ray’s refusal to enter a romantic gay relationship reflects both his individual temperament and the ethos of the gay biker community of that era.

The 1960s and 1970s witnessed a proliferation of motorcycle clubs, gay bars, sex shops, and leather contests. Gear and accessories such as leather jackets, padlocked chains, butt plugs, and Prince Albert rings (as referenced in the film) became visual symbols of gay culture.

In the United Kingdom, the Gay Bikers Motorcycle Club (GBMCC) was founded in 1977 as a club for gay men and women bikers. It is the largest LGBT+ motorcycling club in the United Kingdom and Europe, with a current membership approaching 500 (GBMCC website). Apart from motorcycle clubs, whose primary qualifying criterion is to own and ride a motorbike, there are also leathermen and fetishmen clubs, which are based on sartorial choices and sexual preferences. For example, founded in 1973, MSC (Motor Sport Club) London changed its name to London Leathermen in 2016 to facilitate online searches and to acknowledge that most members today do not need to own a motorbike to legitimise their love of leather. London Leathermen is a club for people interested in leather, rubber and uniforms, and it prides itself on “enduring fellowship”: in an era of social media, “there is more and more demand for gay and bi men to come together in real life, to hang out in gear, build lasting friendships, and forge a community that can stand the test of time” (London Leathermen website).

Historically, the film industry has not been particularly supportive of gay people, often portraying them as criminals and sexual deviants. The film Cruising (William David Friedkin, 1980) offers the public a glimpse of the cruising scene in a gay leather bar, and one of its central characters is a gay murderer. The message of the film seemed clear: unconventional sexuality should be punished. The film was widely regarded as “exploitative” of the gay community and was boycotted by queer activists.

In the twenty-first century, there has been an increasing mainstreaming of queer cinema, from Brokeback Mountain (dir. Ang Lee, 2005) and Call Me by Your Name (dir. Luca Guadagnino, 2017), which were marketed towards a general audience, to Netflix’s commissioning of Pose (2018– ) and Heartstopper (2022– ). Queer culture has never been so ubiquitous on screen, although one could argue that queer culture has never been so precarious on screen. How many gay series have been commissioned beyond their first season? Channel 4’s It’s A Sin is an example.

Some critics lament the “de-sexualisation” of queer culture: queer people are increasingly represented as nice, sweet, “boy-next-door” types, palatable for the tastes of a heterosexual audience. Queer sex, especially non-normative sexual practices, has largely disappeared from the screen. Call it heteronormativity or even homonormativity: when queer culture becomes mainstreamed and normalised, packaged for a general audience and box office success, it not only loses its political edge, it also becomes incredibly dull.

In this context, Pillion is an important film in the recent history of queer representation on screen. Colin and Ray voluntarily enter into an unconventional TPE relationship. They are accepted by the gay bikers’ community and form radical intimacy with other members of that community. Colin’s mother, Peggy, questions the foundation and legitimacy of such a relationship by applying conventional heteronormative criteria. This causes Colin to doubt himself as well. He emerges from the relationship a more confident person, knowing better what he wants while remaining insistent on having a sub/dom dynamic.

In comparison with Adam Mars-Jones’s book Box Hill, which I reviewed earlier this year for Cha, and on which the film is based, the adaptation presents stronger characters with more nuanced and engaging backgrounds. Both Colin and Ray are wholly convincing, thanks to the superb performances of Harry Melling and Alexander Skarsgård. Peggy, portrayed with brilliance by Lesley Sharp, introduces significant dramatic tension to the story and serves as a counterpoint to Ray’s perspective. One might argue that the most compelling moments of the film are not the explicit sex scenes, but the quotidian acts of cooking and serving food, dining together, walking into a hallway and going to bed, or not. Given the dynamic between the two men, everything they do in everyday life is charged with erotic intensity.

The adaptation from page to screen is a masterclass in its own right: the plot is tighter and more compelling, and the characters are more rounded and believable. Although we lose Colin’s distinctive first-person point of view from the book, and the enigma that comes with an unreliable narrator, we are rewarded with a richer, more layered narrative. The film also takes full advantage of cinema’s unique potential: the visual and tactile experience of Colin riding a motorbike is breathtaking. One feels it both corporeally and emotionally while seated in the cinema.

Finally, the film maintains a symbiotic relationship with the gay community, particularly the gay bikers’ community. There has been considerable media speculation about Skarsgård’s sexuality, yet such voyeuristic journalism misses the point. The director, Harry Lighton, spent a weekend with members of GBMCC while researching for the film. GBMCC members also served as advisors and participated in the filming process. They formed a strong bond with the cast and crew, and their involvement shaped the film in powerful ways. As Skarsgård acknowledged inan interview:

We had members of GBMCC Gay Biker Motorcycle Club playing themselves in the film. They were instrumental in shaping all those group scenes, the kind of dynamic between Ray and the other bikers, so it’s really nice and reassuring to have those guys around us throughout the whole experience. The guys from the motorcycle club were so invested in the project and believed in Harry’s vision so much. We premiered at Cannes earlier this year. A bunch of the guys from GBMCC drove down to Cannes to be there. That was a day, a late night that I’ll never forget, to have that celebration. It’s the first time I watched the movie with an audience. To do that with the bikers was an incredible experience and very special.

In many ways, this is a film made with and about gay bikers. It is a gay bikers’ story told by themselves and from their own perspectives, supported by an empathetic cast and crew. If there is a direction towards which future queer cinema should move, it is this symbiotic relationship between filmmakers and the queer community. Queer cinema should not exploit a community or cast a voyeuristic and objectifying gaze upon it, as in the case of Cruising. It should work closely with and for the community, enabling its members to tell their own unique stories.

Pillion offers a radical representation of queerness on screen in an era when queer cinema has become increasingly normalised and uninspired, catering to the tastes of middle-class families. Its radical quality does not, and should not, lie merely in the depiction of kinky sex. Rather, it lies in how the film explores a radical and overlooked community history, while reimagining a bold queer political vision of alternative forms of family and kinship, created together with members of the queer community.

Notes:

Pillion had its world premiere at the 2025 Cannes Film Festival in the Un Certain Regard section on 18 May 2025. The film had its United Kingdom premiere on 18 October 2025 at the Southbank Centre as part of the BFI London Film Festival. It will be released theatrically in the United Kingdom by Picturehouse and Warner Bros. Pictures UK on 28 November 2025. You can read Hongwei Bao’s review of Box Hill here.

How to cite: Bao, Hongwei. “Representing Radical Queer Love on Screen: Harry Lighton’s Pillion.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 20 Oct. 2025, chajournal.blog/2025/10/20/pillion.

Hongwei Bao is a queer Chinese writer, translator and academic based in Nottingham, UK. He is the author of Queer China: Lesbian and Gay Literature and Visual Culture under Postsocialism (Routledge, 2020) and Queering the Asian Diaspora (Sage, 2025) and co-editor of Queer Literature in the Sinosphere (Bloomsbury, 2024). His poetry books include The Passion of the Rabbit God (Valley Press, 2024) and Dream of the Orchid Pavilion (Big White Shed, 2024). [All contributions by Hongwei Bao.]