茶 FIRST IMPRESSIONS

茶 REVIEW OF BOOKS & FILMS

[REVIEW] “The Mountains Speak: The Himalayan Arc” by Abhinav Tulachan

Namita Gokhale (editor), The Himalayan Arc: Journeys East of South-east, HarperCollins India, 2018. 352 pgs.

Namche Bazaar has always been my most favourite place I have ever visited. It is a small Sherpa town nestled between the Himalayan ridges, the last major stop before the long trail to the Everest Base Camp. It is the place I associate my fondest memories with; the place where I first saw snow fall from my bedroom window, where the pine forests each morning smelled of resin and cold, of fresh earth, and where the morning mist would drape itself like a soft blanket over the still-sleeping town until it felt almost mystical.

“Wake up,” it would whisper, “Put on your boots. There is a whole sky to walk under.” These nostalgic memories, beautiful, stubborn and regrettably shaded by the sorrows and pain I am about to speak of in this review, are but one story among the thousands that the Himalayas hold.

Poems and short stories, personal anecdotes and even in-depth interviews: calling The Himalayan Arc merely something as straightforward as a “book” feels as though I am doing it a grave disservice. It is, first and foremost, an anthology; or to elaborate even further, a “convergence” of diverse genres and voices by an equally diverse catalogue of contributors that together paint a single yet multifaceted portrait of the Himalayan regions. With an astonishingly diverse range of references, whether it be Ronid “Akhu” Chingangbam’s lyrical protest poem, a heart-stopping vignette of the 2015 earthquake by Susham, or a tête-à-tête with the King of Bhutan, author Namita Gokhale presents a veritable buffet of perspectives to choose from, which I find especially ironic at the time of writing, given that one of the contributions focuses on mountain cuisine.

With thirty-six prominent authors, among them Prajwal Parajuly and Manjushree Thapa, both of whose pieces I have discussed, readers are constantly left anticipating what comes next. One moment, you may be tracing the spice-tinged aroma of gundruk (a fermented leafy green vegetable popular in Nepal) fermenting in a Nepali courtyard; the next, immersing yourself in a psychogeographical lament on Sikkim’s economic transformation. You may even find yourself eavesdropping on a monarch’s vision for his people’s prosperity.

Yet despite its almost dizzying variety, regardless of the journey each transition takes you on, from Nepal to India, to Bhutan, Myanmar, and all the way back again, every piece in this “creatical” (my professor defines it as “a combination of critical and creative writing techniques”) roadmap ultimately returns to the same theme: what it means to have lived, and to live, in and around these mountains.

Perhaps, to best elaborate on this notion, I should start with one of the earlier entries in the anthology, Operation Mustang, a first-hand fieldwork investigation into Nepal’s Maoist insurgency.

On paper, the first narrative, Bell’s, reads like a typical academic paper at first glance. It is filled with historical data and meticulous dossiers of information that one expects to find in a chronicle. Yet, as you gradually settle into that mode, the creatical element emerges unexpectedly as Bell immerses himself directly in the case: a coded transcript of a late-night interview, a conversation with an informant in an abandoned hotel garden (who was part of the operation), Bell himself uncovering information by trekking into areas of intrigue. The tension suddenly becomes electric and heart-pounding, so vivid that you, the reader, feel as though you have become an active participant in unravelling this old case, acutely aware of every footstep and every breath drawn in the shadows as you walk side by side with the author. He employs fiction in the service of what is seemingly non-fiction, yet I find it fascinating how real the story nonetheless feels.

Then comes the following chapter, The Quake, which strikes the reader with a first-person vignette that plunges them into the very heart of the 2015 Nepal earthquake from the instant the ground begins to shudder. The opening line shocks with “a rain of bricks”, and the magnitude of Joshi’s piece is immediately felt: “I thought somebody was hitting me with bricks from behind.”

Her narrator, a foreigner without the language or the instinct of the locals, has no time to think, no time to process, as pillars of wood and brick, debris from a temple, collapse all around her.

“It took me a while to register that this was real. This just happened. This wasn’t fiction. This was the real deal, an apocalyptic accident of unimaginable horror that we think lies safely within the pages of books and on cinema screens, but that we will never experience in real life.”

“An incident I had never imagined would happen to me, until it did.”

The desperation that fills the story from this point is overwhelming as the temples fall. Roofs split overhead, masonry rains down, and all the while, the anguished cries of survivors tear through the chaos before being abruptly silenced. For a moment, as I read those sentences, part of me felt as though I was back in the middle of that tragic day, with no time to think and no time to process, just as Joshi herself writes: “Everything happened in the fraction of a second.”

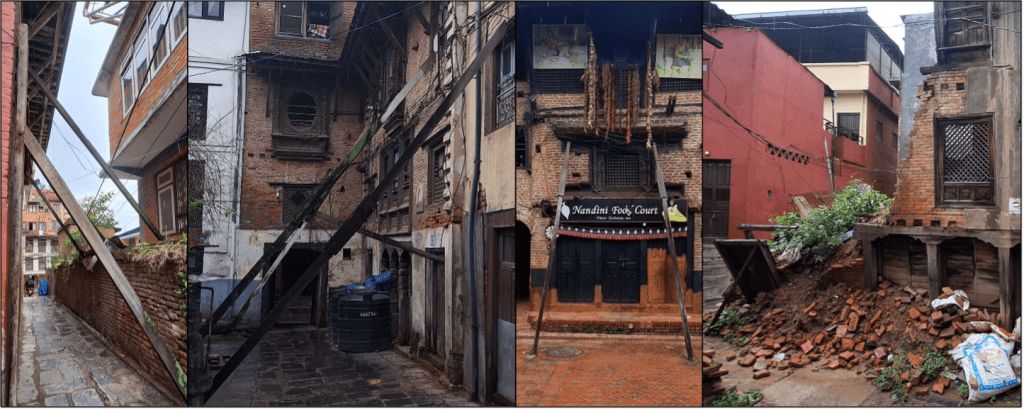

She gives literary form to a collective trauma that lives within us as memory. Interestingly, her first instinct while enduring a disaster of that magnitude is to rummage desperately through her mind in search of a reference from fiction, yet she finds none. Having lived through that disaster myself in 2015, too young then to comprehend what was truly happening but old enough to remember the rumbling, I found Joshi’s account achingly and hauntingly true. Even today, the scars left by the earthquake remain etched across Nepal, and no matter how much preparation one undergoes or how many years pass, as the author herself describes, it is impossible to forget.

(From left to right) Photographs taken at Patan Durbar Square during my recent visit. Lingering rubble from collapsed buildings and metal beams supporting those still on the brink of collapse. An entire decade has passed, yet the aftershocks of that dreadful day remain plain to see, a scar the city has yet to heal.

But to step back for a moment, let us now turn to India. Indra Bahadur Rai, Andrew Duff and Binodini have all contributed their own respective entries, whether through short stories or personal reflections on Darjeeling and Manipur. Yet what stood out to me most was Prajwal Parajuly, who once again returns to my writing with two short stories, both rooted in or skirting the Himalayan territories, both places I once visited in what feels like another lifetime.

As a writer from Sikkim, and as someone who longs to live there permanently, Parajuly in Sikkim: A Home Full of Hotels observes the region’s economic boom brought about by tourism, and cannot help but mourn its cost. He shares personal anecdotes of how lodges are built while cottages are demolished, how families are sustained but the spirit of Sikkim fades. With every development, Parajuly notes, and almost laments, the gradual erasure of his hometown. “In our attempt to accommodate tourists, we are becoming indistinguishable from other hill stations.”

Parajuly acknowledges the jobs and infrastructure these hotels bring. He understands that progress is inevitable, and that progress and livelihood are inseparable, even as he mourns the disappearance of the very beauty that once defined Sikkim’s allure, the lands that made Sikkim itself.

In contrast, though not entirely dissimilar, his story Downhill in Darjeeling reflects on the region’s declining economy and growing political tensions. The hills themselves seem to weep at the departure of their youth, as Darjeeling’s faltering economy forces many to seek prosperity abroad, a reality hauntingly similar to Nepal’s current struggles. In a sense, one might consider how, even when divided by borders, beliefs or topography, those who live around these mountain ranges share similar struggles. These are connections forged through experience, shaped by common suffering and memory. On one hand lies the collective trauma of the Nepal earthquake; on the other, the collective loss of what once made Sikkim, Sikkim.

The contributors to this anthology are doing what history has often failed to do, or chosen to forget, by unearthing stories that national narratives have long glossed over, whether cultural, historical, economic or political. Nowhere is this more evident than in the final entries from Myanmar.

Salil Tripathi’s Pacifist Prisoners and Militaristic Monks traces the history of Myanmar’s brutal military regime and the Rohingya crisis, through which around a million people have been displaced. Her writing references Ma Thida, one of Burma’s most celebrated dissidents and writers, who in A “Fierce” Fear reflects upon the deep-rooted decay in Myanmar’s society, a decay that rises from its very foundations. It is an examination of how violence was bred, how corruption spread, and how self-preservation came to supersede all else. Perhaps most devastatingly, it reveals how this cycle of violence has become the norm. “The long dictatorship has taught Myanmar’s people that problems are solved only through violent reprisal and social discrimination.”

These final entries culminate in an essay by David Malone retracing his journeys through Bhutan, Nepal and Nagaland. All bear witness to the resilience of those who have resisted and continue to resist. Yet most importantly, the entries throughout remind us that the lived experiences of the people of these regions are deeply intertwined, even if divided by land and lines.

Some entries may not appeal to every reader, while others may resonate deeply and unexpectedly. Yet coming from someone who is neither politically inclined nor particularly drawn to poetry, I implore you to approach each entry and each landscape with a touch of curiosity and openness. That is the beauty of an anthology like The Himalayan Arc: there is always something waiting to surprise you, to challenge your assumptions, and to move you in quiet, unforeseen ways.

Look closely. Listen carefully. See for yourself what it means to have lived, to be living, and to continue living in these mountains. Let the voices speak.

How to cite: Tulachan, Abhinav. “The Mountains Speak: Namche Bazaar’s The Himalayan Arc.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 16 Oct. 2025, chajournal.blog/2025/10/16/himalayan-arc.

Abhinav Tulachan is an undergraduate student in the Department of English Language and Literature at Hong Kong Baptist University. He loves reading, writing, and sharing the knowledge he has gained through his academic journey. [All contributions by Abhinav Tulachan.]