Editor’s note: Ratan Bhattacharjee’s essay on Amitav Ghosh’s 2025 Pak Kyongni Prize win situates this landmark recognition within the broader terrain of world literature and ecological thought. Ghosh’s achievement underscores the moral and imaginative strength of diaspora writing, linking history, environment, and identity. The piece explores how his work, grounded in postcolonial and ecological awareness, reflects the prize’s ethos of moral imagination. It reminds readers that literature’s enduring power lies in its capacity to illuminate, connect, and bear witness to our shared world.

The highly prestigious international literary award, Pak Kyongni Prize, often called the “Korean Nobel”, recognises a lifetime of achievement in literature. Its conferral on Amitav Ghosh this year is particularly significant, as he joins the ranks of diaspora writers whose work transcends the boundaries of culture, ecology, history, and memory. In a moment of literary history that resonates deeply across continents, Indian author Amitav Ghosh has been awarded the 2025 Pak Kyongni Prize of South Korea. This essay explores Ghosh’s literary journey, the importance of the Pak Kyongni Prize, and what this recognition signifies for the global landscape of postcolonial and ecological literature.

To understand the full weight of Ghosh’s achievement, one must consider the prize itself. Established in 2011 by the Toji Cultural Foundation, the Pak Kyongni Prize (박경리 문학상) is named for the late Korean novelist Pak Kyong-ni (1926–2008), best known for her epic Toji (The Land). The award honours lifetime literary achievement and the kind of moral or imaginative vision that the foundation associates with Pak’s legacy. The prize carries a cash award of ₩100,000,000 (one hundred million won), which is among the largest literary awards in South Korea. Depending on exchange rates, this has been represented in press accounts as being worth around US $75,000 to US $100,000. It is awarded annually (usually in October) and is widely regarded as one of Korea’s foremost international literary honours.

Previous laureates include writers of global renown such as Marilynne Robinson (2013), Amos Oz (2015), Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o (2016), A. S. Byatt (2017), and Ismail Kadare (2019). Amitav Ghosh has, for decades, stood as one of the central figures in modern world literature. Born in 1956 in Calcutta and educated in India and the United Kingdom, Ghosh has built a body of work that resists simple categorisation. His fiction is richly historical, expansive in its geographic and temporal reach, and intricately engaged with ecological and civilisational themes. His non-fiction is sharp, urgent, and morally attuned, especially in an age when the climate crisis, displacement, and the legacies of colonialism are not mere backdrops but existential realities.

Among his best-known works are The Shadow Lines (1988, Ravi Dayal Publisher), The Glass Palace (2000, HarperCollins), the Ibis Trilogy—Sea of Poppies (2008, John Murray), River of Smoke (2011, John Murray), and Flood of Fire (2015, John Murray)—The Hungry Tide (2004, HarperCollins), Gun Island (2019, John Murray), The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable (2016, University of Chicago Press), and The Nutmeg’s Curse: Parables for a Planet in Crisis (2021, John Murray). His recurrent themes include migration and diaspora, the burdens and erasures of colonial history, and the entanglements between human societies and the natural world. Ghosh’s writing insists that nature itself must be regarded as a subject, less a stage for human drama than a living presence, a witness, and at times, a victim.

The citation for the 2025 Pak Kyongni Prize notes that Amitav Ghosh is honoured for “expanding the frontiers of postcolonial and ecological literature and for giving voice to subaltern subjects, including nature itself”. This resonates strongly with the original intent of the prize: to recognise not only literary craft but also moral courage and an attention to those often left unheard, whether human or non-human, silenced by history, power, or environmental neglect. There is a profound eco-critical dimension to this recognition, the understanding that the dangers confronting human societies through environmental destruction are intimately bound up with histories of colonialism, economic inequality, and dispossession.

In both his fiction and non-fiction, Ghosh persistently connects the global with the local, the vast forces of trade, empire, and migration with the intimate landscapes of memory and survival, from the Sundarbans to the Indian Ocean world. His achievement lies in his ability to combine archival research, narrative plurality, and lyrical power, marking him as a writer of exceptional scope and insight.

Another vital aspect is the question of diaspora. Ghosh is not Korean, yet his work has always spoken across borders. The prize’s international ethos, reflected in its diverse list of laureates from Africa, Europe, and the Americas, underscores its commitment to global voices. In selecting Ghosh, the jury affirms the value of a writer whose affiliations transcend national and cultural boundaries. It recognises that the universal often arises from the particular, and that global concerns such as climate change, colonial legacies, and migration require equally global literary voices.

Amitav Ghosh’s win may be seen as a vindication of what it means to be a diaspora writer today: one who carries memory, navigates belonging and estrangement, and resists the flattening narratives of globalisation. Diaspora writers have sometimes been perceived as existing in a liminal space, too global for local traditions, yet not fully embraced by the literary norms of the cultures they engage. Ghosh transcends that divide, treating places as porous, alive, and interconnected through histories, migrations, and ecological relations. His award signals that the global literary community increasingly honours work that refuses to simplify complexity or to shrink from moral stakes.

For Indian literature in English, and for literatures of the Global South more broadly, this is a moment of affirmation. The notion of “world literature” has too often implied Western literature translated into many tongues; Ghosh’s work reverses that paradigm. His narratives privilege the epistemologies, geographies, and histories often marginalised in the Western canon. That such work is now recognised by a major international prize like the Pak Kyongni is evidence of a slow but genuine shift towards a more inclusive vision of global literature.

Of course, literary awards are symbolic. They cannot, by themselves, remedy the crises of climate change, displacement, poverty, or the enduring aftershocks of colonialism. Yet they matter. They draw attention, foster dialogue, and widen readerships. They enable translation, circulation, and funding for future work. Ghosh’s recognition may encourage younger writers across the Global South to engage with the larger themes of the planet, history, and ecology, not only questions of identity or belonging but the intersections among them.

However, such recognition also carries a risk: the danger of tokenisation or superficial reading, celebrating “the ecological writer from India” without engaging with the depth of his ideas. There is also the possibility of co-option, where literary markets and institutions reward fashionable themes like climate or ecology without acknowledging their deeper urgency. Yet the Pak Kyongni Prize, with its emphasis on moral imagination and subaltern awareness, appears to have made its selection in earnest. It asks of its laureates not comfort but conscience, to insist, provoke, and connect.

This award also reflects something of Korea’s growing role in the global cultural landscape. In recent decades, Korean literature, cinema, and music have gained immense international influence. The prestige of the Pak Kyongni Prize, and its increasingly diverse list of winners, demonstrates a widening of cultural exchange across South–South, East–West, and North–South dimensions. Korea is not merely exporting its culture; it is extending recognition to non-Korean and non-Western voices. For readers in India and elsewhere in Asia, this may encourage deeper cross-cultural engagement through translation, collaboration, and dialogue, and remind authors that their readership can indeed extend far beyond familiar borders.

Amitav Ghosh’s environmental imagination is rooted in lived history, in the intertwined legacies of colonialism, trade, and ecological disruption. His fiction treats the natural world not as setting but as character. His seas, winds, and forests bear memory and meaning. His attention to deep time, the slow rhythms of landscape and the sediment of culture, anchors his critique of modernity’s short-termism. The Ibis Trilogy, The Glass Palace, and The Shadow Lines explore the moral and material consequences of empire, the migrations it unleashed, and the ecological and cultural costs of expansion.

In his later works, particularly The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable, Ghosh argues that literature has failed to confront the scale of the climate crisis, treating it as an exception rather than a central narrative concern. He calls for a reimagining of storytelling in which nature becomes an active agent. His more recent fiction, including Gun Island, enacts this vision, bringing myth, migration, and climate crisis into a shared frame, where dolphins, storms, and serpents speak alongside human protagonists.

Central to Ghosh’s literary ethics is his commitment to amplifying marginalised voices, both human and non-human. By recovering suppressed histories and reimagining silenced worlds, he insists that literature remain accountable to the past, to the dispossessed, and to the earth itself.

Amitav Ghosh’s receipt of the 2025 Pak Kyongni Prize is therefore more than an individual accolade. It is a statement that literature from the Global South, concerned with history, ecology, and justice, stands at the heart of world letters today. It is a victory for conscience, imagination, and the belief that storytelling still has ethical weight. For young writers, students, and readers, it is a reminder that art matters, that it can interpret, challenge, and reimagine the world. For the earth and all its silenced voices, human and otherwise, this honour acknowledges their stories. And for Ghosh, it is richly deserved.

This prize strengthens not only his resolve but also that of countless others who write from the margins, from histories of erasure, and from landscapes that are changing under our feet. May literature continue to serve as a site of resistance, remembrance, and renewal.

How to cite: Bhattacharjee, Ratan. “Amitav Ghosh’s Pak Kyongni Prize 2025: A Diaspora Writer’s Triumph.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 15 Oct. 2025, chajournal.blog/2025/10/15/Amitav-Ghosh.

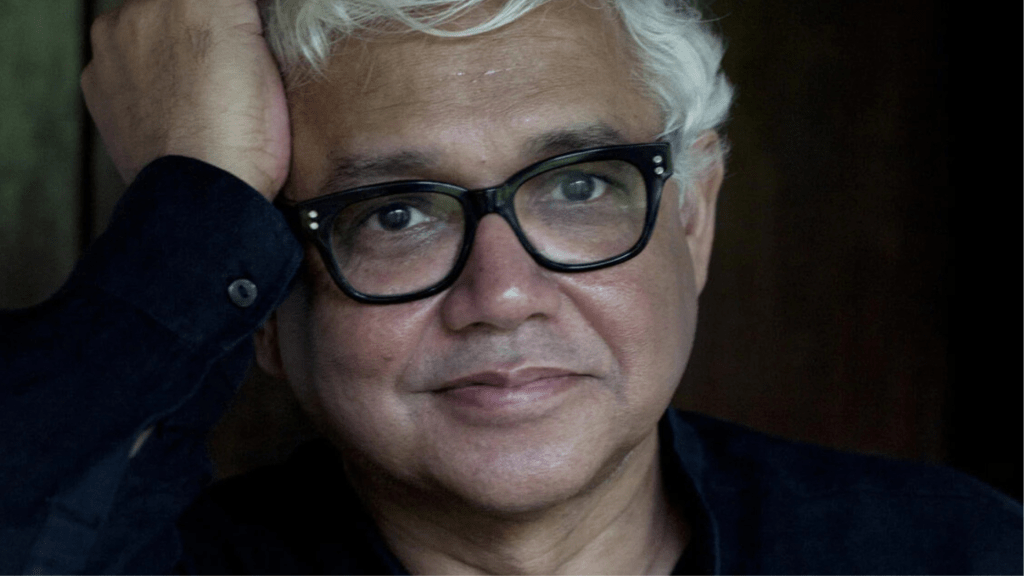

Ratan Bhattacharjee, winner of the 2024 International Tagore Award (DRDC UK & India), is a distinguished multilingual writer, poet, and columnist. Formerly an Affiliate Faculty member at Virginia Commonwealth University and President of the Kolkata Indian American Society, he is also a Founder Member of the International Theodore Dreiser Society, Philadelphia. With nearly four decades of teaching experience in India and abroad, he made his poetic debut with The Ballad of the Bleeding Bubbles (Cyberwit, 2014), followed by Oleander Blooms (Authorspress, 2015), which earned him the title “Oleander Poet of India”. His other notable works include Six Feet Distance (Bloomington, USA), Francis Scott Fitzgerald (Partridge Singapore, 2020), Theodore Dreiser: Going Beyond Naturalism (INSC, 2021), and Our Time Revisited (IIP, 2025). His poetry collections Renee, Rudhagni, and Our Daughter Our Princess have been widely translated and published across Europe, South Asia, America, and Canada.