📁 RETURN TO FIRST IMPRESSIONS

📁RETURN TO CHA REVIEW OF BOOKS AND FILMS

Johannes Schönherr, North Korean Cinema. A History, McFarland, 2012. 224 pgs.

My experience with the three books on North Korean cinema I had read up to this point—Paul Fischer’s A Kim Jong-Il Production (2015), Immanuel Kim’s Laughing North Koreans (2020), and Kim Jong Il’s On the Art of the Cinema (1973)—is that such works, however narrowly focused they may appear—Dr Kim’s monograph being a study of North Korean comedy films; Fischer’s a nonfiction novel recounting the alleged abduction of South Korean director Shin Sang-ok and his wife, the actress Choi Eun-hee, their years of enforced filmmaking in North Korea, and their eventual escape—almost invariably provide at least some summary of North Korea’s relatively brief history and the development of its film industry in relation to political events and their repercussions. Kim Jong Il’s treatise does not, of course, since it constitutes part of the historical record of North Korean cinema rather than a commentary upon it. By contrast, Immanuel Kim’s study consistently invokes political events or the prevailing economic situation at given moments—and the ways in which policy decisions shaped them—as context for the films he analyses. Meanwhile, Fischer’s hybrid of filmmaker’s biography, true crime, and international political thriller, boasts entire chapters dedicated to such contextualisation.1 Thus, after reading a handful of books of this kind, it is easy to feel that one has already traversed the full extent of North Korea’s cinematic history—particularly if one has also read more general works on North Korea, where the same core information on the nation’s social, cultural, and political history tends to recur from one volume to the next.

Yet it becomes evident, upon reading North Korean Cinema: A History by the German author, globetrotter and unusual film hunter, and consequently North Korean cinema expert, Johannes Schönherr, that although the three aforementioned books are certainly essential reading for anyone interested in the films of the Hermit Kingdom, Schönherr’s quasi-compendium on the subject is at least equally indispensable for any library.

First of all, it is anything but narrowly focused. It explores in detail the development of the principal genres of North Korean cinema, beginning with the national origin story films, including the “Immortal Classics” Sea of Blood (1969) and The Flower Girl (1972), or the so-called first North Korean movie, My Home Village (1949): epic period melodramas2 designed to construct and perpetuate the “myth” of Kim Il Sung’s unhistorical “Korean People’s Revolutionary Army” single-handedly liberating Korea from Japan’s brutal colonial occupation (p. 29). The film genre nomenclature also encompasses the “war films,” which portray North Korea as a country “continuously under threat” from “foreign powers ready to attack or subvert the country” (p. 34), the “romantic comedies depicting North Koreans as leading the most carefree, happy lives imaginable” (p. 7), and the “Films on the Theme of the Socialist Reality,” which are socialist-realist dramas “dealing with daily life in industrial plants, in collective farms” and “addressing personal shortcomings of members of the new society and their misguided behaviour” (p. 38).

Although Schönherr’s book is not, like Paul Fischer’s, specifically devoted to Shin Sang-ok’s captivity and North Korean filmography, it is highly effective in conveying how pivotal a figure Shin was in the dictatorship’s film culture. It first explains how Shin “introduced new genres like the martial arts film and the monster movie, and brought fantasy and eroticism into North Korean cinema” (p. 5), through three chapters that catalogue Shin’s own cinematic achievements during his DPRK years, other North Korean productions of the same period that displayed Shinian influence, and, finally, films that briefly carried forward Shinian ambitions to explore alternative approaches to filmmaking in the years following the South Korean director’s escape.3

In addition to this tripartite analysis of Shin’s impact, the book concludes with three interviews with North Korean defectors about their experiences as filmgoers in Sinuiju, Pyongyang and Ryanggang. Their broadly unanimous sentiment that “the traditional [North Korean] films were so boring, we wanted to see Shin’s films” (p. 194), or that “after the Shin Sang-ok era, we had new eyes” and “we could judge which movies are interesting and which are not” (p. 192), provides striking vindication of Schönherr’s argument that Shin’s films paved the way for the subsequent disaffection North Koreans displayed towards their local propagandistic cinema and their eagerness for the illicit viewing of foreign films, particularly those from America, Hong Kong and South Korea, smuggled in through China.

Then the book clearly delineates the different periods in the country’s film history and in its broader historical context. Various film genres have been produced more or less throughout every era (except, of course, for those imported by Shin), but there has usually been one or two genres that dominated the output depending on the period and circumstances. The formative years of the nation and regime (from the mid-1940s to the early 1960s) were dominated by socialist-realist dramas, although My Home Village, the first of the origin story or “liberation myth” films, was released at the very beginning. The Korean War (1950–1953) also initiated the seemingly unending barrage of war films.

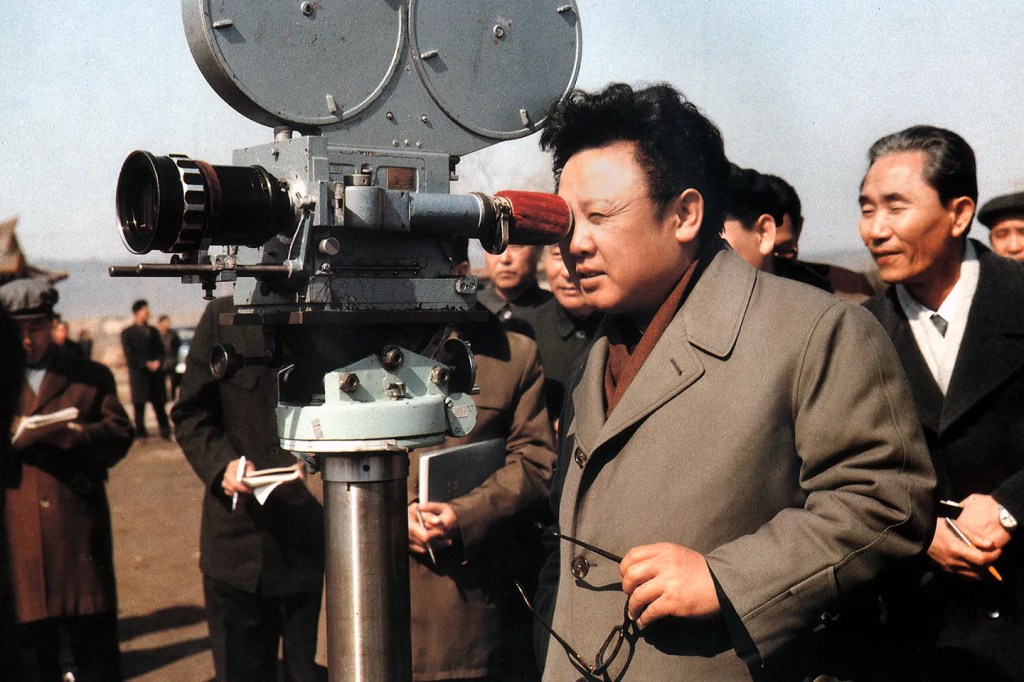

In the late 1960s and 1970s Kim Jong Il began to be directly involved in film production, and during this period the “Immortal Classics” with which he was most closely associated, and which essentially functioned as the country’s “tentpole” films, included major origin story or “liberation myth” works: Sea of Blood, The Flower Girl and The Star of Korea (1980), as well as other period epics depicting nationalist resistance against Japanese occupation, such as An Jung Gun Shoots Ito Hirobumi (1979). Other projects launched under Kim’s direction included the television spy series Unknown Heroes (a project inspired by similar East German and Czech productions),4 as well as further socialist-realist dramas such as The Problem of Our Family (1979) and its nine sequels.

The 1980s (from 1983 onwards) were very much the era of Shin’s films, from the extravagant fantasy of the ninja-and-flying-monks epic Hong Kil Dong (1986), to the socialist-realist-drama-turned-grindhouse Salt (1985),5 to the famously campy kaijū movie Pulgasari (1985),6 but also of works by others seeking to imitate him and provide crowd-pleasing spectacles rather than tedious Juche lectures. Among these was the highly entertaining Order No. 027 (1986), essentially a North Korean counterpart to Enzo G. Castellari’s The Inglorious Bastards (1978), but with an abundance of martial arts sequences throughout.

Hong Kil Dong

After the escape of Shin and Choi Eun-hee came a return to basics, with the re-emergence of heavily propaganda-laden socialist-realist dramas, particularly the stay-in-your-village films such as A Broad Bellflower (1987; referred to simply as A Bellflower by Schönherr) or My Happiness (1987). Schönherr characterises the “messages” of these films as “slabs of lead sinking onto the heads of the viewers” (p. 104).7 Subsequently, as Kim Il Sung died, the Soviet Union collapsed, China opened its markets, and the devastating famine of the 1990s (the “Arduous March”) took hold in North Korea, the nation’s cinema screens came to be dominated by the light-hearted comedies mentioned earlier. These were designed to present North Koreans as the happiest people on earth, living in the most modern, prosperous and pleasant of societies, even as the majority of their audience were struggling to survive, resorting to eating weeds, drinking rice water or, in some cases, consuming the flesh of deceased relatives.

A Broad Bellflower

Finally, Schönherr’s book also considers the period of South Korea’s “Sunshine Policy,” when the then-liberal president Kim Dae-jung and his successor Roh Moo-hyun sought to foster friendlier relations between the two Koreas. Cinematically, this period saw two distinct trends emerge north of the DMZ. On the one hand, there were films whose unaltered propaganda messages continued to present to North Korean audiences a national narrative defined as the DPRK against the world, such as Green Shoulder-Strap (2000) and Son Comes Back Home (2000). On the other hand, there were films that attempted to emulate Shin’s entertaining brand of filmmaking, trying to make productions that are, like his, theoretically marketable abroad. Among other things this resulted in the delicate, subtle and relatable, though still gently propagandistic, drama A Schoolgirl’s Diary (2006). During this same period, there was also the remarkable case of a Westerner producing three North Korean-approved documentaries within the country: the British director Daniel Gordon, with his sports documentaries The Game of Their Lives (2002) and A State of Mind (2004), as well as his film on the American defector James J. Dresnok, Crossing the Line (2006). As if to confirm Paul Fischer’s contention that the film producer Kim Jong Il was less a leader than a follower (see footnote 4), Pyongyang’s Korean Film Studio also released what it described as the “North Korean version” of James Cameron’s Titanic (1997), entitled Souls Protest (2001). It adopted the same romantic approach to another historical and tragic maritime disaster, this time involving North Koreans, for which blame was laid on Japan by the DPRK.

Internally, however, the “us versus the world” mentality remained so deeply entrenched that, as Schönherr observes at the conclusion of his extensive overview, when right-wing forces regained power in South Korea with the election of Lee Myung-bak in December 2007 and the termination of the Sunshine Policy, films were released in the North—such as the three 2008 productions Call of Naval Port, Follow What We Are Doing and The Lieutenant in Those Days—that had necessarily been produced during the Sunshine years, yet were still “anti-South military propaganda” (p. 168). Perhaps, then, the tragic moral of the book is that a leopard cannot change its spots.

In any case, another strength of Schönherr’s work is that, despite the vast span of time, events and film productions encompassed in his chronology of the DPRK’s film industry, it never reads like a mere catalogue of dates and titles. Instead, it is punctuated throughout by a considerable number of film reviews, some brief and others highly detailed. To call it comprehensive in this regard would be an exaggeration, for the task of reviewing all 259 films supposedly made in North Korea between 1945 and 1998 (according to a booklet issued by the “(North) Korea Film Export & Import Corporation” in that year [p. 23]), together with the uncertain but evidently substantial number produced between 1998 and 2012, would in any case be impossible, particularly since many of these films are no longer accessible. Schönherr himself regularly notes in the course of his historical narrative that a given film was “not available for review.”

There is, moreover, the issue of selection: from the immense corpus of material, it is necessary to choose those items that are not only representative but also relatively engaging and illustrative of his points. For example, I recall two light-hearted comedies that I watched while reading Schönherr’s book but which he does not mention at all—A Family Bright with Songs (1977) and A Traffic Controller on Crossroads (1986). The former is noted in Immanuel Kim’s Laughing North Koreans, albeit under a different title (“A Family Shining in Music”). Although I found them both pleasant and not without interest, I would be hard pressed to argue that their inclusion would have been indispensable in the context of North Korean Cinema: A History.

In any event, the number of reviews included is enormous, and anyone seeking discussion of My Home Village, The Tale of Hung Pu (1963), My New Family (date uncertain), A Flourishing Village (1970), Sea of Blood, The Flower Girl, An Jung Gun Shoots Ito Hirobumi, The Road I Found (1968), The Fate of Kum Hui and Un Hui (1974), Unknown Heroes, The Star of Korea, Wolmi Island (1982), The Tale of Chun Hyang (1980), An Emissary of No Return (1984), Love, Love, My Love (1984), Runaway (1984), Salt, The Tale of Shim Chong (1985), Pulgasari, Thousand Miles Along the Railroad (1984), Run and Run (1985), Order No. 027, The Separation (1985), A Silver Hairpin (1985), Thaw (1986), Hong Kil Dong, Rim Kkok Jong (1986–1993), A Bellflower, My Happiness, Traces of Life (1989), An Urban Girl Comes to Marry (1993), Nation and Destiny (1992–2002), The Forest Sways (1997–2000), Myself in the Distant Future (1997), Stalks Grow from the Roots (1998), Girls in My Hometown (1997), Forever in Our Memory (1999), The Earth of Love (1999?), Souls Protest, On the Green Carpet (2001), A State of Mind, Our Fragrance (2004), A Schoolgirl’s Diary, Song of the East Sea (2009) or the delightfully inept 1988 action film Ten Zan: The Ultimate Mission (an Italian–North Korean co-production directed by Ferdinando Baldi, filmed in English in North Korea and featuring both Italian and American actors), will certainly find what they are looking for in this monograph, along with numerous perceptive observations on many other films.

The Flower Girl

There are evidently many films that may be regarded as “bad,” not only in the case of entertainingly silly or camp accidents such as Pulgasari or Ten Zan, but also among the numerous serious dramas, war films and even comedies. Many of these ultimately amount to tedious lectures on fabricated history and oppressive political injunctions, poorly disguised as plodding works that appear to have been made decades earlier than their actual year of production.

Yet, as the preceding paragraphs have shown, there are also genuine little gems, even if the serpent of propaganda occasionally raises its head within them. As for the less successful works, Schönherr addresses them succinctly in an interview he gave to the British film critic Simon Fowler for his website on North Korean cinema. When asked, “Are the films any good?” Schönherr replies:

That is certainly one of the discoveries awaiting the curious reader of Schönherr’s book: odd and fascinating behind-the-scenes stories and anecdotes, whether for dystopian history buffs and political enthusiasts, or for cinephile “geeks” like myself. Among the former is the account of Han Soon Hee, the real-life farm worker on whom the protagonist of Traces of Life is based. She became chairwoman of the management committee of her collective farm in South Pyongan, was repeatedly praised and visited by Kim Il Sung, awarded the “Hard-Working Hero Title,” and made a delegate to the Supreme People’s Assembly. She was later arrested and executed for alleged espionage in what was essentially a purge of Kim Il Sung’s close associates engineered by Kim Jong Il when he came to power, and was posthumously rehabilitated by Kim Jong Il in 2000 (pp. 107–108). For the latter, there is the revelation that “Edoki Jun,” the pseudonym used by the Japanese distributor of Pulgasari when writing for the Japanese edition of Playboy, is a bilingual pun on the name Ed Wood Jr (pp. 146–148).

Moreover, Schönherr’s History includes a review of Kim Jong Il’s On the Art of the Cinema (pp. 54–56), which offers useful perspective and context for my own reading (and that of others) of Kim’s essay as a hollow imitation of technical and theoretical discourse, deployed in order to produce what might be called the vacuous works of Captain Obvious: 330 pages explaining to the seemingly five-year-old workers of the North Korean film industry that a plot must be good, that music and actors are important, and that water is wet and the sun emits light. The one substantive point, perhaps, is that films must not deviate from the ideological line of Juche propaganda, which Kim pseudo-poetically refers to as the “seed” of the film, to be embedded at the start of every plot. My conclusion was that, with such a “bible” for North Korean filmmakers, it is hardly surprising that it eventually seemed as though the only solution to rescue the nation’s cinema was to bring in a foreign director, whether willingly or not.

Schönherr’s interpretation of the vacuity of Kim’s treatise, however, is both different and illuminating, and in retrospect self-evident. According to him, the problem is not merely that, despite his much-vaunted passion for cinema, Kim Jong Il had no genuine insight into this art form and was only obsessively concerned with its role as a vehicle for propaganda. That may have contributed to the treatise’s shortcomings, but the more convincing explanation is that its emptiness reflects Kim’s contempt for the filmmakers he was addressing. It is not so much that Kim lacked deep thought about cinema, for in fact an On the Art of the Cinema written by Tommy Wiseau might actually have been more insightful, but rather that in his unselfconscious despot’s mind the manifest deficiencies of a substandard and internationally unmarketable national cinema could only be the result of extreme stupidity on the part of the filmmakers themselves, rather than the severe limitations imposed on them by the regime in terms of subject matter and exposure to global ideas, art and culture.

In addition, Schönherr emphasises, with equal force, that there was virtually no difference between the quality of films produced before the publication of On the Art of the Cinema and those made afterwards. The book merely advocated what the earlier films had already been doing, and thus Kim’s “thoughts” contributed no intellectual value to filmmakers and had virtually no impact.

One point about the phrase “willingly or not,” which I used earlier. That is another interesting element of Schönherr’s book: unlike Fischer, and unlike the authors of the comic Le Dictateur et le dragon de mousse and the creators of the television series Kim Kong (see footnote 1), Schönherr is explicit, both in his book (p. 75) and in his 2011 paper on Shin’s North Korean films, about his uncertainty as to whether Shin was really kidnapped or whether he in fact defected to the Hermit Kingdom, later fabricating the kidnapping once he had defected back to the ROK.

Fischer acknowledges in the afterword to his book that “[t]here are many, especially in South Korea, who do not believe Shin Sang-Ok and Choi Eun-Hee were kidnapped by North Korea, but that they defected to Pyongyang willingly,” but his purpose in this afterword is to debunk what he regards as mere “hypotheses” and the multiple and oft-repeated “inaccuracies” which he argues underpin the case against the veracity of Shin’s and Choi’s testimonies. By contrast, when Schönherr refers to the kidnapping, he always frames it so as to remind the reader that the two stars’ account remains controversial: “Both claimed later that they had been kidnapped to North Korea” (p. 5); “If we believe what Shin Sang-ok said about the events later […], they were both kidnapped by the North Koreans […]. But should we believe Shin?” (p. 75); “Kidnapped by North Korea or not, Shin and Choi took the chance and made a run for the American embassy there” (p. 89).8

Both authors cite a book that appears to be an important reference for the anti-Shin sceptics. It seems to be impossible to locate online at the time of writing this review, nor can information about its author be easily found, but Fischer refers to it as The Fictional Image, whereas Schönherr suggests that it exists only in Japanese and cites it more precisely as Kyokoo no Eizoo (Fictional Image) (p. 75), providing full bibliographical details in an endnote (“Tokyo: Hihyoo-Sha […], 1988” [p. 206]). The author’s name is apparently 西田 哲夫, transliterated by Fischer as “Nishida Retsuoh” and by Schönherr as “Tetsuo Nishida” (p. 75).

The descriptions of Nishida and his 1988 allegations could hardly be more polarised. For Schönherr, Nishida is (or was) a “Japanese film critic and early friend of Shin Sang-ok” and “[h]e says that Shin Sang-ok told him […] before disappearing […] that he had gotten an offer from North Korea to make movies there freely—and that he considered going there voluntarily.” So, because Mr. Nishida is assumed (or has been ascertained?) to be a reliable source, it follows from this that Shin may very well not be.9 However, under the pen of Paul Fischer, Nishida has become “a Japanese journalist who claimed to know Shin” (emphasis mine), and Fischer then points out that the name “Nishida Retsuoh” is a pseudonym, and, after vouching for his own due diligence as far as cross-referencing, verifying and corroborating every possible statement of Choi’s and Shin’s, he writes, about The Fictional Image, “I read the book and found that it […] is full of errors”—before proceeding to list them and explain in what ways they are errors. So there certainly seems to be a lot of cloudiness and confusion around the main reference text of those who doubt Shin’s testimony. Schönherr never accuses the director of lying in so many words, but he does seem to lean that way when he writes “should we believe Shin?” in his book, or, even “one should take the kidnapping story with a grain of salt” in his Film International article on North Korean film history—both phrasings that are much less neutral than a mere “some people do not believe Shin’s story,” or “many people question Shin’s story.” I wonder if the film historian has read Fischer’s afterword or any other pro-Shin’s-story plea since the distant year 2012, and if he has been convinced by them (which is difficult to ascertain as he seems to have mostly written about Japan, rather than North Korea, in the years since). I am certainly not better equipped (to be clear, I am far less equipped) than the specialists whose writings I am here discussing to reach an unimpeachable verdict on the question of the trust that must be put in Shin’s and Choi’s testimonies. Yet, if I may give my two cents, although the statement “Given that [Shin] was severely at odds with the [then dictatorial] South Korean government and couldn’t work in the South anymore, it certainly made sense for him to consider such an opportunity [as the offer to work freely in North Korea]” (p. 75) is technically true (but hypothetical, as Fischer points out), a statement like “Given that it has been abundantly documented that Kim Jong Il’s North Korea was in the habit of kidnapping many foreigners, and that it is also accepted (including all throughout North Korean Cinema: A History) that Kim Jong Il was very passionate about improving the standards of North Korean filmmaking, it certainly made sense for him to decide to kidnap a renowned foreign filmmaker and to force him to make films in North Korea” is just as technically true (and just as hypothetical).

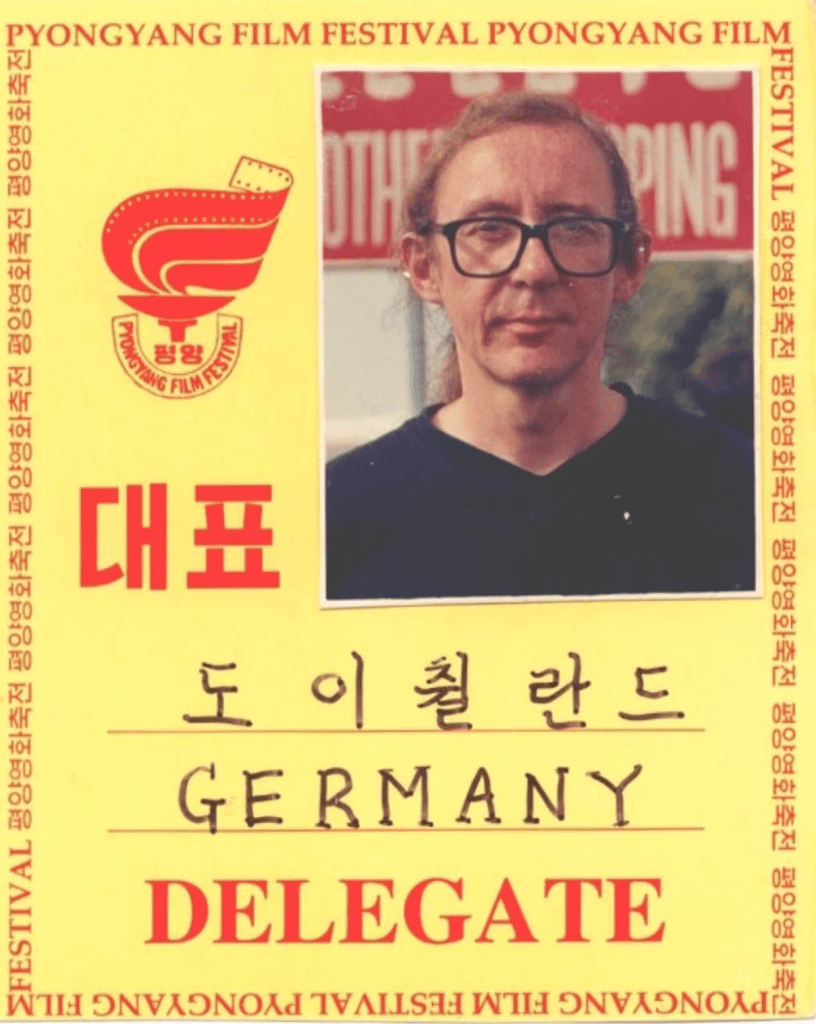

Apart from the historical chronology, the review of On the Art of the Cinema, and the many film reviews, the book also gives interesting accounts of the genesis and several of the successive programmes of the Pyongyang International Film Festival (initially called the “Pyongyang Film Festival of the Non-Aligned and Other Developing Countries”), and shows how those programmes reflect, each year, the degree of confidence (or lack thereof) Kim Jong Il had in his nation’s film output—and, on top of all those treats and the very interesting (and aforementioned) interviews of defectors about their experience as former DPRK-based filmgoers, Schönherr’s generous book also provides, after the detailed review of Ten Zan: The Ultimate Mission, an interview with Ferdinando Baldi, the Italian director of the film, who graciously offers us another glimpse of the craziness that may ensue if someone decides to go to North Korea to make films (unless that someone is Daniel Gordon, apparently).

So, if you are interested in a strange journey into film, as a “stranger in a strange land”, and if you have decided that North Korea is the strange land for you, but that books are probably a better means of going there than an actual plane—more practical, far less restricted, and much less dangerous—Schönherr’s North Korean Cinema: A History will certainly be a very important stopover on your route. There probably needs to be a sequel today, though, as there have been so many changes in the thirteen years since the publication of that book. Kim Jong Un had barely taken over power from his late father at the time (p. 1). There is so much more that is known about him today. Kim Jong Nam had not been assassinated by his ruling brother, then (p. 45). North Korea was not yet a nuclear power, and it is today. What is the impact on the content of their war films? What is the impact of Kim Jong Il being replaced by a leader who is not at all as obsessed with cinema? The phrase “President Donald Trump” was not even a thing in 2012—nor was the renewal of some sort of “Sunshine Policy”, at least in the form of a new, short-lived attempt at a rapprochement between the Koreas during Moon Jae-in’s presidency in South Korea.

There are only two post-Schönherr North Korean movies that I know of. One was released in 2012 and is called Meet in Pyongyang by its Youtube uploaders, A Promise Made in Pyongyang by the North Korean Archives and Library website (although when you enter their Dropbox, the file is actually entitled Meet in Pyongyang again; so I’ll let the people who actually know the Korean language decide what the best translation is, based on the Internet Movie Data Base, which only provides the original title). Its story of a cultural exchange between two young female dancers, an aspiring great from China and a North Korean Arirang coach seems to echo the centering of the North Korea/China friendship focused on in the movie Brothers’ Feelings (2010), briefly evoked towards the end of Schönherr’s book (p. 170), and its reviving of the legacy of the Chinese volunteers who fought alongside North Korean soldiers in the Korean War (or, as they lyingly call it in Meet in Pyongyang, the “war of US aggression”). Simultaneously, the “luxury postcard from Pyongyang” visual mood of this quiet and uneventful drama (including large excerpts of an actual Arirang show) seem to reflect or foreshadow the brief period, pre-COVID crackdown, of rapid modernization of Pyongyang and apparent greater openness to foreign visitors that seemed, initially, to partly define Kim Jong Un’s leadership style (to the point that a French tour book publisher actually produced one for North Korea). As for the second film, The Story of our Home (2016), it seems to be mostly about imitating the successful formula of A Schoolgirl’s Diary: mixing together socialist realist drama on people’s everyday problems and light-hearted movies about the joy of living in the happiest place on Earth; focusing on children characters, because they are cute and when they are sad or happy, viewers will be sad or happy too; showing how the great people of North Korea heartily help each other, and how it is great to sacrifice one’s life, hopes and dreams for others and for the glory of the nation, while singing songs in praise of the incumbent leader. This obviously needs more context, and more subtle understanding of the inner workings of that creative industry under tight influence. So, please, a sequel, Mr Schönherr or some yet unknown disciple of his (although, at the present time, it is probably much more difficult to go there or to get access to as great a number of movies and documents as the ones Schönherr was able to get hold of).

In any case, North Korean Cinema: A History remains an essential resource for anybody who might wish to start such a project, or any other kind of study or intellectual exploration of the world of film in the Kim family’s gated fiefdom.

Kim Jong Il “guiding” filmmakers on set

A scan of the identification card from the 2000 Pyongyang Film Festival showing Johannes Schoenherr, source

- Here in France, the story of Shin and Choi’s ordeal has also inspired a three-part TV miniseries entitled Kim Kong (2017; created by Simon Jablonka and Alexis Le Sec and directed by Stephen Cafiero) and a comics album entitled Le Dictateur et le dragon de mousse (2024; script by Fabien Tillon, art by Fréwé; the title means “The Dictator and the Rubber Dragon”). However, the TV show is a satirical fictionalisation of the real story—with an imaginary and single French director in lieu of Shin, and the backdrop of a fictional, unnamed Asian dictatorship and its fictional, unnamed leader, which very recognizably stand for North Korea and Kim Jong Un, but that is still resolutely not nonfiction in spirit (and the fictional strongman does not visually evoke the right Kim, substituting the current, basketball-loving tyrant for his late film-buff father). Besides, instead of demanding from the kidnapped director a North Korean version of Godzilla, as Kim Jong Il demanded of Shin by commissioning the making of the sole North Korean kaijū movie Pulgasari (1985), Kim Kong’s dictator wants his French prisoner to film a local version of King Kong! As for the comics story, it is very much a condensed version of A Kim Jong Il Production, abridged enough to fit in about 126 pages of “sequential art” instead of the 330 pages or so of prose of Fischer’s book. Obviously, with those approaches, neither of those French creative renderings of Shin Sang-ok’s North Korean experience devote any space to broad historical contextualisation. ↩︎

- Actually, although it has (very beautiful) visual, musical and emotive qualities that were somewhat reminiscent, to my ignorant Western eyes, of The Sound of Music (1965), The Flower Girl is obviously not steeped in joy like most of Wise’s film. On the contrary (except at the end, when the protagonist’s brother comes back to tell his home village folks of Kim Il Sung and they all gladly join his resistance movement), Choe Ik Gyu and Pak Hak’s “Immortal Classic” is such an immensely sorrowful melodrama that it makes Akira Kurosawa’s Red Beard (1965) seem as cheerful as Singin’ in the Rain (1952) in comparison. ↩︎

- For those interested in that specific part of his research, Schönherr had already developed similar reflections on Shin’s North Korean “career” and its impact on the rogue nation in a paper published the year before his book (i.e. in 2011), in issue 22 of the Japanese journal 社会システム研究 (Shakai shisutemu kenkyū) [Social Systems Research]. ↩︎

- In the words of Paul Fischer: “it was Kim Jong-Il who had made a habit not of leading, but of following: of copying foreign successes he had just seen and enjoyed. Nation and Destiny was an answer to a long-running film series in Japan, Unknown Heroes a rip-off of German and Czech spy thrillers, The Flower Girl an extension of classic Chinese melodrama.” Obviously, Schönherr also points out the fellow Eastern bloc inspirations for Unknown Heroes, although more in detail and not as a jab at Kim Jong Il (p. 61). ↩︎

- I have not seen it, but it is basically how Schönherr describes it: “Choi’s acting presence combined with the dirtiness, bodily fluids and violence all around her make Salt an extraordinary piece of cinema. It feels like 1970s exploitation meeting socialist-realist art” (p. 81). ↩︎

- The Godzilla film franchise, starting with Ishirō Honda’s 1954 film, is obviously a clear inspiration for Pulgasari, as both Fischer and Schönherr (p. 82) acknowledge—in as much as Pulgasari is a giant bipedal reptile, vaguely reminiscent of tyrannosauri and the like, but also in as much as Shin got the Japanese special effects crew of the Godzilla films, including Kenpachiro Satsuma, the actor who played Godzilla (under a rubber suit), to come to North Korea and work on the film, with Satsuma donning the Pulgasari suit (cf. Fischer, p. 285 and Schönherr, p. 84). However, as a little bit of a kaijū aficionado myself, I am struck by the fact that Pulgasari’s plot is nothing like any of the Godzilla films’ ones, and that (with its monster-aided medieval peasant rebellion against tyrannical lords) it is very close to the stories of another Japanese kaijū franchise, the Daimajin trilogy, whose three constitutive films were all released in 1966. So, there are obviously other explanations (as Schönherr points out, “North Korea has a long history of films featuring medieval rebellions” [p. 84]), but I cannot help wondering whether Shin knew the Daimajin films, and whether they played any subterranean part in influencing the direction Pulgasari’s plot took. ↩︎

- To be fair, A (Broad) Bellflower, a melodrama in which leaving one’s very poor rural home village to go find a job in the city is considered as a major crime akin to mass murder, child trafficking, or defiling a corpse, is as aesthetically gorgeous as it is ideologically dumb and psychopathic. ↩︎

- Emphasis mine in the three quotations. ↩︎

- The year before, Schönherr had already made the same point, using the same source, in an article titled “Permanent State of War: A Short History of North Korean Cinema,” posted in March 2011 on the website of the journal Film International. ↩︎

How to cite: Camus, Cyril. “North Korean Cinema, A History: Rise (and Fall?) (and Rise again?) of the Propaganda Machine.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 11 Oct 2025, chajournal.blog/2025/10/11/korean-cinema.

Cyril Camus teaches English to post-secondary students at Ozenne High School in Toulouse and is an associate member of the Cultures Anglo-Saxonnes research group of Toulouse University. He wrote Mythe et fabulation dans la fiction fantastique et merveilleuse de Neil Gaiman (2018), a monograph on Neil Gaiman’s works, Sang de Boeuf (Bouchers et acteurs) (2019), a historical horror novel about the Grand Guignol Theatre, and academic papers on Neil Gaiman, Alan Moore, comics, music, rewritings of Shakespeare, and postmodern fantasy. He also co-edited a 2021 journal issue on the themes of societal and environmental collapse in fantasy and science fiction. Visit his website for more information. [All contributions by Cyril Camus.]