TIFF 2025

▞ 10. The Archivist’s Film: A Conversation on Kunsang Kyirong’s 100 Sunset

▞ 9. She Was Screaming into Silence: A Conversation on Cai Shangjun’s The Sun Rises On Us All

▞ 8. You Don’t Belong to Anyone: A Conversation on Kalainithan Kalaichelvan’s Karupy

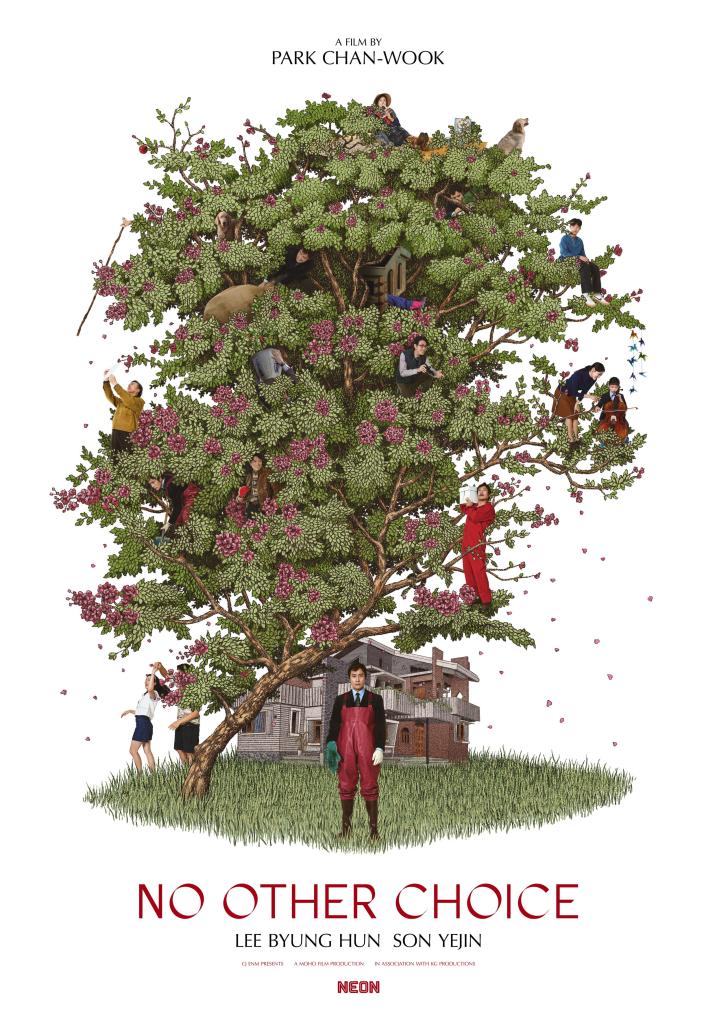

▞ 7. The Paper Boy: On Park Chan-wook’s No Other Choice

▞ 6. Saigon Does Not Believe In Tears: On Leon Le’s Ky Nam Inn

▞ 5. The Need for Change: On Kei Ishikawa’s A Pale View of Hills

▞ 4. The Angel of Death: On Jafar Panahi’s It Was Just An Accident

▞ 3. Of Eros & Of Dust: On Ratchapoom Boonbunchachoke’s A Useful Ghost

▞ 2. Light At The End of the Labyrinth: On Genki Kawamura’s Exit 8

▞ 1. Affairs of the Heart: On Cai Shangjun’s The Sun Rises On Us All

Park Chan-wook (director), No Other Choice, 2025. 139 min.

No Other Choice is a rather easy film to interpret.

From the outset, when its hero, Man-su (Lee Byung Hun), the patriarch of a family of four and a long-time employee of a paper manufacturer, feels he has reached a point of fulfilment in life, it is promptly followed by his forced dismissal, after which every aspect of his life and identity crumbles. The cause of his and a handful of other men’s termination is attributed to American influence, downsizing, and the implementation of AI, which not only threatens but effectively renders their existence obsolete. Days, weeks, and months pass, yet Man-su fails to secure another position, forcing the family, almost upper middle-class, to cut back on certain privileges: their pair of dogs must be sent away, the couple must quit ballroom lessons, but it is the spectre of losing their home, which we learn once belonged to Man-su’s family and which he had worked hard to “buy back”, that compels him to become more creative in his approach to securing a job he views as enviable, so that they may return to the life they once had.

In a critical scene, set on a rooftop, Man-su, coming off yet another failed interview, spots Choi Seon-chul (Park Hee-soon), a social media star and manager at a rival paper company, down below, perfectly positioned for a potted plant to fall on his head. Since this is a film directed by Park Chan-wook, adapted from a novel by Donald E. Westlake, and co-written by Lee Kyoung-mi, Jayhe Lee, and Don McKellar, a twist reliably ensues: he realises that killing the person in the coveted role does not exclude the remaining candidates. What No Other Choice then proceeds to do is dramatise the turbulent process of following through with eliminating them, producing a fair share of violent disorder along the way.

The pleasure of a major work by Park Chan-wook lies in his ability to surprise the viewer on a dramatic level. In an early work such as Oldboy (2003), this occurs at the film’s climax, when Dae-su (Choi Min-sik) learns that the woman he has been sleeping with, Mi-do (Kang Hye-jeong), is in fact his daughter, and that the events of the film leading up to this revelation, designed by a vengeful Lee Woo-jin (Yoo Ji-tae), were not accidental but deliberate acts of cruelty. In a more recent work such as The Handmaiden (2016), it occurs after the climax, on the boat, when we learn that Lady Hideko was not as innocent as she appeared, and that she was fully aware of the plot surrounding her from early on, meaning that Sook-hee (Kim Tae-ri) and Count Fujiwara (Ha Jung-woo) were doubly and more deceptively deceived.

For the most part, this film, which premiered at the Venice Film Festival to rave reviews yet went home empty-handed, does not engage in this kind of development, since it proceeds in a rather classical manner, moving from the elimination of one employee to the next. What operates on the surface, therefore, is the dramatic irony that derives from Man-su keeping a secret of which the audience is fully aware, while the characters within the film are not. At the screening I attended, which was sold out, this resulted in much laughter, making me wonder whether its popularity was directly tied to this approach, one that made the audience feel like confidants to the director’s vision, which appears to be viewed as almost godlike and beyond reproach.

As his career has progressed, Park Chan-wook’s approach to cinema has evolved in other arenas. Working with editor Kim Sang-bum and cinematographer Kim Woo-hyung, Park continues the cinematic innovations explored in films such as Stoker (2013) and Decision to Leave (2022), deploying stunningly original transpositions, special-effects-assisted compositions, and, notably, the intricate sound design by Kim Suk-won and Eunjung Kim. Rather than being spread evenly across the image, sound is often inserted to the right, left, front, and back of the soundscape. During the first kill, rather than stage the scene straightforwardly, Park has Man-su turn up the volume on the stereo so that the characters are shouting over it, requiring Korean subtitles. The relief, once it ends, lies in the sudden aural absence. During his third kill, an extreme close-up of a glass of beer, followed by an interior perspective of the cup, further immerses us in his world. Subtle gestures such as these elevate the otherwise unoriginal plot and transform the film into an experience in which Park utilises all the tools at his disposal to create new textures from familiar tropes, a project he has always been intent on pursuing.

Rather than conclude on a note suggesting that humans are inherently evil, or that shatters our conception of morality, No Other Choice seeks to turn our gaze towards our own world: the intersection of capitalism and globalisation, the rise of automation, and the fact that our lives are precarious and fundamentally dependent on others. The wicked lesson that Man-su learns by the film’s end can be distilled into simple phrases such as “be careful what you ask for” or “the grass is greener on the other side”. It is a film that speaks to the everyman, the one who feels out of place and unemployed, who feels shut out from doors they have repeatedly knocked upon, who begins to lose faith in the vitality of their future. Man-su is entertaining to watch precisely because he is not a good killer; he writes himself into conundrums from which he can never cleanly or swiftly escape. If not the authorities, then it is his family, his wife Mi-ri (Son Ye-jin) and son, who observe his increasingly erratic behaviour once he relapses and goes on a bender. Instead of placing one’s life in another’s hands, one has the agency to make one’s own choices, whether benevolent or malevolent. “How can you not change with the times?” Man-su asks once he realises he will be working with robots. How can you not sell your soul to make a living?

How to cite: Nagendrarajah, Nirris. “The Paper Boy: On Park Chan-wook’s No Other Choice.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 7 Oct. 2025, chajournal.blog/2025/10/07/no-other-choice.

Nirris Nagendrarajah (he/him) is a Toronto-based writer whose work has appeared in paloma, Polyester, Fête Chinoise, In the Mood Magazine, Tamil Culture, in addition to Substack. He is currently at work on a novel about waiting. [All contributions by Nirris Nagendrarajah.]