TIFF 2025

▞ 10. The Archivist’s Film: A Conversation on Kunsang Kyirong’s 100 Sunset

▞ 9. She Was Screaming into Silence: A Conversation on Cai Shangjun’s The Sun Rises On Us All

▞ 8. You Don’t Belong to Anyone: A Conversation on Kalainithan Kalaichelvan’s Karupy

▞ 7. The Paper Boy: On Park Chan-wook’s No Other Choice

▞ 6. Saigon Does Not Believe In Tears: On Leon Le’s Ky Nam Inn

▞ 5. The Need for Change: On Kei Ishikawa’s A Pale View of Hills

▞ 4. The Angel of Death: On Jafar Panahi’s It Was Just An Accident

▞ 3. Of Eros & Of Dust: On Ratchapoom Boonbunchachoke’s A Useful Ghost

▞ 2. Light At The End of the Labyrinth: On Genki Kawamura’s Exit 8

▞ 1. Affairs of the Heart: On Cai Shangjun’s The Sun Rises On Us All

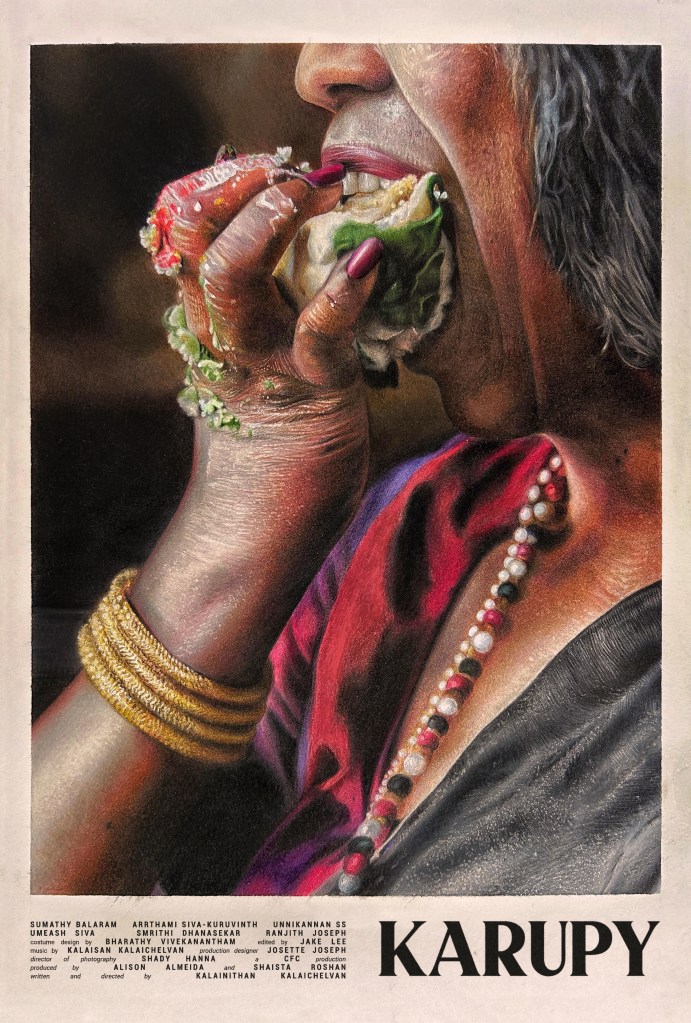

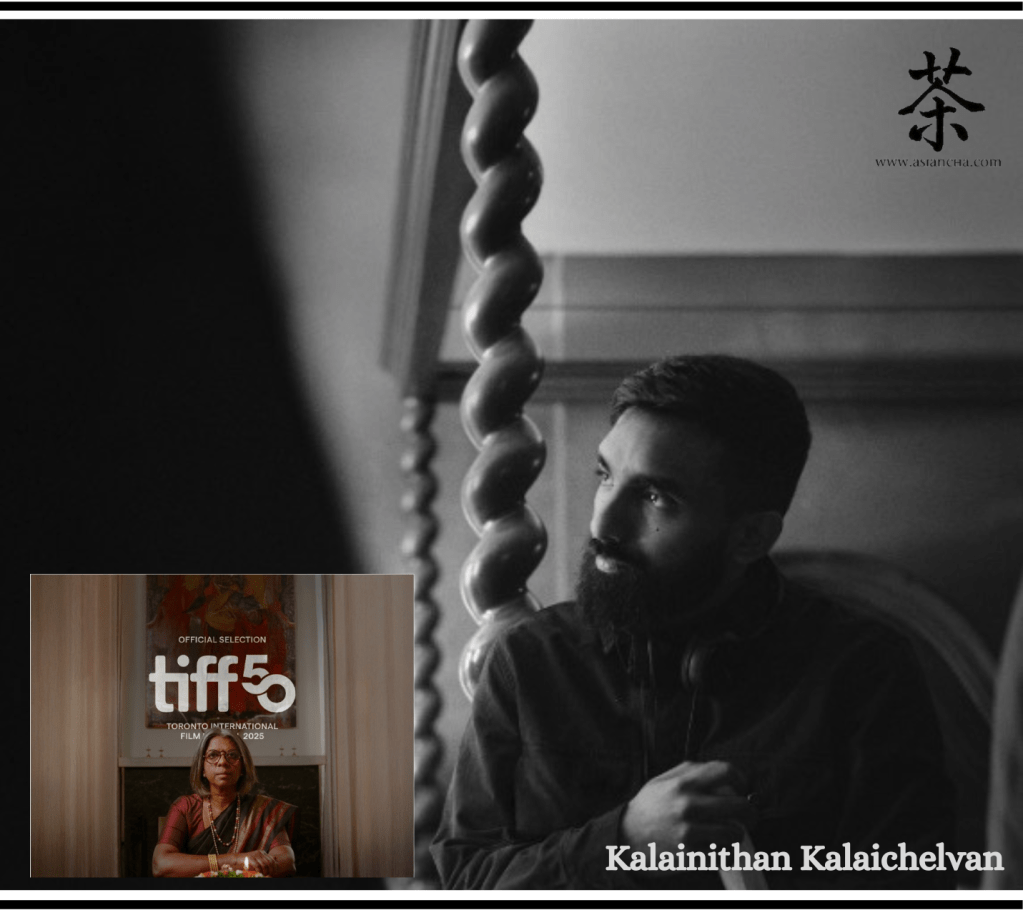

Editor’s note: We are pleased to present a conversation between our resident film critic, Nirris Nagendrarajah, and director Kalainithan Kalaichelvan, whose latest short film, Karupy, had its world premiere on 9 September 2025 in the Short Cuts programme at the Toronto International Film Festival. Their exchange explores the film’s defiant reimagining of the Tamil matriarch, its darkly comic confrontation with death, and Kalaichelvan’s enduring commitment to rendering diasporic life with specificity, grace, and uncompromising cinematic vision.

Kalainithan Kalaichelvan (director), Karupy, 2025. 12 min.

INTRODUCTION

Nirris Nagendrarajah

The short film, like the short story, is a form in which some filmmakers truly flourish and, despite progressing to feature-length works, continually return to. Filmmakers such as Martin Scorsese, Christopher Nolan, Jane Campion, Lynne Ramsay, Spike Jonze and Sofia Coppola began their careers by pushing the boundaries of the short, akin to the constraints of a commercial or music video, where traces of their future genius were already palpable in these concise strokes of cinematic imagination.

Since 2017, director Kalainithan Kalaichelvan has built a career and developed his voice across ten short films that bring a modern sensibility to diasporic themes, managing to both evade and perhaps confront what it means to be a second-generation Asian immigrant creating art within a predominantly white industry. How does one make films that are culturally specific without rendering them inaccessible to others? How does one speak to one audience without alienating another? Film after film, Kalaichelvan appears to have fashioned an answer.

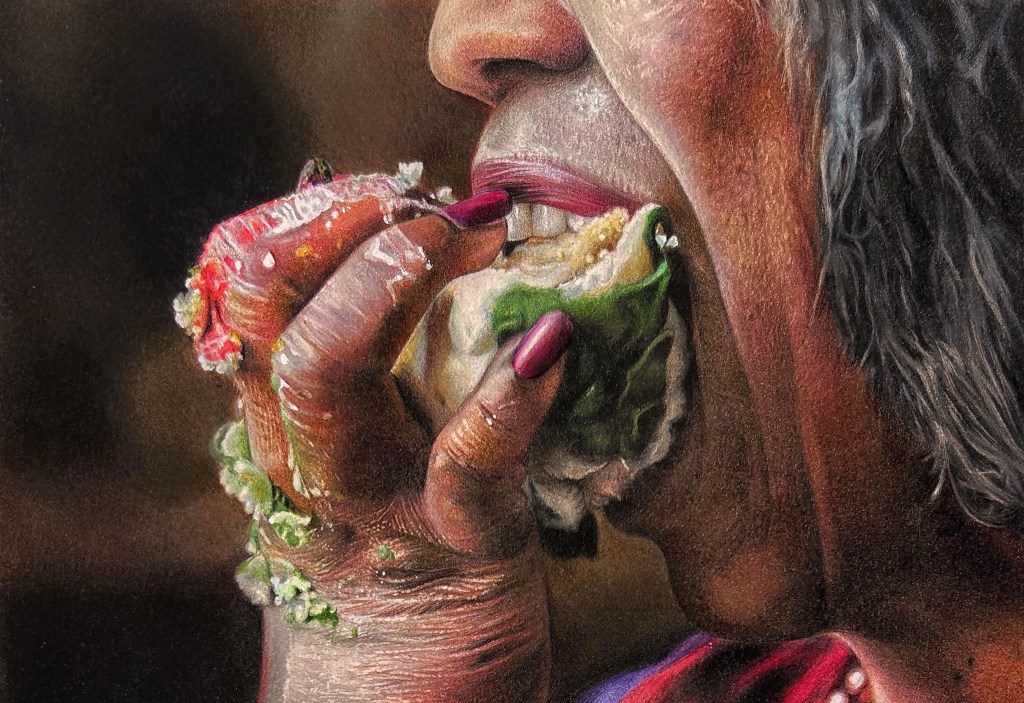

His latest film, Karupy, which had its world premiere in the Short Cuts programme at the 2025 Toronto International Film Festival, centres on the titular character (played by a superb Sumathy Balaram) who, during her sixty-fifth birthday celebration, announces to her family and friends that she intends to end her life at its conclusion. As one family member after another attempts to dissuade her, what emerges are waves of anger, dark comedy, buried secrets and delicious cruelty. Karupy, rather than conforming to the archetype of the docile South Asian wife, is sharp, unflinching and mean, and the film mirrors her wicked nature and defiant spirit.

With highly stylised cinematography by Shady Hanna, recalling Robbie Ryan’s collaborations with Yorgos Lanthimos, and a macabre score by composer Kalaisan Kalaichelvan, Karupy, created under the Norman Jewison Program at the Canadian Film Centre, delivers a striking impact within its twelve minutes and heralds a compelling new voice in contemporary cinema.

I had the pleasure of speaking with Kalainithan via email on the eve of the film’s premiere.

A Conversation

on Karupy

Nirris Nagendrarajah & Kalainithan Kalaichelvan

Nirris Nagendrarajah (NN): The history of the matriarch in Tamil cinema offers enough material for a dissertation. There is the fair, dutiful wife who cooks for the family and is always impeccably dressed, adorned with gold jewellery and a yard of jasmine pinned into her braid. At the other extreme, there is the dark-skinned, impoverished and despondent mother who has prematurely lost her husband and struggles to survive, placing all her hopes for the future upon her prodigal son, the hero of the narrative. Heroines in Tamil cinema are invariably love interests and rarely mothers, and if they are, they possess no trace of evil, for the malevolence of domestic life is reserved for the father.

From the outset, Karupy overturns these tropes. We encounter a dark-skinned woman of a certain age asserting her authority over her own life with commanding resolve, while the passive faces around her, her audience, watch in bewilderment. What was the initial spark, and how did you develop it using the resources provided by the CFC? What were your intentions?

Kalainithan Kalaichelvan (KK): It’s difficult to trace the origins of any project to a single idea. It’s usually a few threads that finally come together and push me to start writing. I’d been wanting to write a story set at a family gathering that explored the hierarchical dynamics between Tamil people across generations. During my time at the CFC, I was already thinking about the character of Karupy, at first in the context of a different story that explored the origins of a dark-skinned matriarch and her reclamation of a name. Separately, I had this image in mind of a shocking announcement that could kick off an entire feature. It took me a while to realise these ideas belonged together, but once I did, the film began to take shape quickly. Through the programme, my focus was on distilling the film down to its simplest, most resonant moments. Along the way, some ideas were buried, others rose to the surface, but the story found its rhythm. I’d also just come off making Junglefowl, which was a film set in Sri Lanka during the civil war. After finishing that, I was hungry to present a Tamil family in a very different environment, with a completely different energy. Karupy came out of that hunger. I was trying to complicate and reimagine the matriarch on screen, and to give her agency in a space where she’s rarely been allowed to have it.

NN: The film contains details that may easily escape the viewer. I admired those brief shots of the dining table displaying the different vadas, rolls and mango lassis, as well as the title cards bearing Tamil names delicately stitched into a tapestry. Whether intentional or not, the daughter, played by Arrthami Siva-Kuruvinth, speaks with an Indian accent, and the painted portrait of the father, which assumes a supernatural quality, appears to be inspired by the image of the actor Kamal Haasan. Why is specificity important to you? What might be present on screen that we do not immediately perceive?

KK: I guess I’ve always been obsessive about detail. It’s not about what people notice; it’s about what’s there. That approach carries into every aspect of making a film. The accumulation of small, specific choices is what breathes life into a world and its characters. That’s why we put as much thought into how someone looks, moves, or speaks as we do into a choice of fabric or a background prop that may never be in focus. It’s all part of the bigger whole, and for those of us behind the camera, it matters just as much as what’s front and centre. It doesn’t always need to be appreciated, but it’s always adding something. As for the painting, I’ll just say my dad is the biggest Kamal Haasan fan. The man in the painting may resemble the actor, but when I look at it, I’m reminded of my own father.

NN: Death, within the Tamil community, is not something one is encouraged to discuss or even contemplate, let alone speak into existence. Karupy’s desire is radical, and its effect reverberates throughout the family, bringing to the surface themes of infidelity, grief and the perspective of the second generation. When I saw the film, I immediately wanted to show it to my mother, who I felt would relate to this woman who, like her, occasionally expresses her discontent with life and her desire to die, which in the moment can seem preferable to living.

Why did you choose to confront death in this way, later linking it to the grief of a patriarch? Does death bring us closer to the truth? What does the song at the end signify?

KK: I wish I knew how to answer this. I’m starting to realise death has a big presence in a lot of my writing. It just keeps finding its way in, uninvited, and it’s annoying. In the case of this film, it came through a moment I had with my grandfather at a family event. He was sick, and when I asked how he was feeling, he said very casually in Tamil, “I don’t want to be here. I’m just waiting to die.” I didn’t know what to say. Another family member quickly jumped in to tell him not to talk like that, that everything would be fine. I’m still trying to figure out why that moment stuck with me. Was it just the way he said it? The matter-of-factness of it? I don’t know. When I started writing Karupy, it became less about confronting mortality itself and more about an enforced silence around our relationship with death. That’s what pulled me in. With the closing song, I debated for a while whether I wanted subtitles for non-Tamil-speaking audiences. Towards the end of the process, I decided not to. It was written to be a few things at once, a song a father would choose for his daughter in that moment, carrying ideas woven into the story that I did not feel needed to be underlined through text. I think it’s best I let it exist in peace. Those lines are safer in the hands of my brother’s music.

NN: It was such a delight to encounter Sumathy Balaram once again, whom I first discovered on stage this past summer in the Fringe production Pornstar (i), whose creators and several cast members appeared in your earlier short A Feller and the Tree. The cast also includes Smrithi Dhanasekar, who plays Vaish, the granddaughter, and is a local dancer and model, while your brother, Kalaisan, is an emerging composer. It is very easy for a second-generation immigrant to make a conscious decision to step away from their ethnic roots and to inhabit and cater to the Caucasian imagination.

What drew me to your work was that you did not do this, yet neither did you fall into the trap of perpetuating the clichés of representation. I admire your style, supported by your use of varied film stocks, which feels in conversation with the work of Yorgos Lanthimos and Jonathan Glazer. How important has it been for you to be part of, and to foster, a community of emerging artists who share similar life experiences and aspirations? What is your ethos as a creator, and how do you allow your influences to shape but not dilute your work?

KK: I’ve never been overly concerned with pandering to the Caucasian imagination, as you put it. A good story will translate, always. A century of cinema proves this. We connect with films from all over the world, so there’s no need to dilute the work with elements that don’t speak to me just to reach broader appeal. I’m only trying to make the films I always wanted to see as a kid. In my mind, they usually feature characters who look a bit more like me, or like the people around me. My storytelling has been shaped by a long, eclectic list of influences, and I’ll continue letting those influences pass through me without letting them dictate who I am. I grew up in the West, so naturally there will be echoes of that upbringing. But I didn’t fall in love with movies because of American cinema, or European cinema. For me, it was South Indian films. Tamil cinema drove me to this path. Those are the films I watched with my family, so now when I imagine my films playing to an audience, I picture Tamil faces in those seats. What puts a smile on my face is the idea of them seeing our culture and experiences reflected on screen in fresh, exciting ways. I’m trying my best to deliver on that.

NN: Finally, after ten short films over the course of eight years, where do you see yourself on your creative journey? Are there plans or ideas for a feature? You have been in the industry long enough to comment on how you perceive the landscape evolving, or perhaps remaining unchanged. One topic that often arises in conversations with independent creators is the difficulty of securing funding for projects, and the even greater challenge of making a profit once that funding is obtained. There are very few voices like yours, whose confident vision seems to become more defined with each successive work.

What were the struggles behind the scenes that led to this moment of debuting at TIFF? What is one thing you would tell your younger self about the process of carving out a creative space, and what would you say to others who wish to tell new stories in innovative ways?

KK: If I told my younger self I’d make ten shorts before ever making a feature, he’d have a meltdown. If I told him none of them would satisfy him, he’d be ready to throw hands. He had anger issues. Honestly, there isn’t much I’d say to him. He’ll learn over time and will continue to fumble his way through it. I’m still fumbling through it. You’re right, funding is difficult. Profit has been non-existent. I’ve kept going by holding onto this delusional idea that if I make great work, the stars must align at some point. So I just focus on the work. Every time I make a film, it consumes my entire world. It robs every minute of my day. Every penny in my pocket. I’d convince myself that it’s all worth it because it’s going towards creating something special. Something truly great… only to then come out the other end feeling like I’ve fallen short. It’s frustrating and a little embarrassing. But that’s how it is every single time. A decade of that cycle can be deflating. We all know the industry is hard, and at times damn near impossible to navigate. It doesn’t help that a lot of us measure the worth and value of our work by the recognition we get from festivals and awards. Without them, a film may not have much of a life, and so the film fades. And with it, the filmmaker. Or at least it can feel like that. I try to remind myself it’s the body of work that matters. I look back at the stuff I’ve made so far, some of them not very good, only a few received notable recognition. Yet they are mine, and they probably paint a better picture of me than I’m willing to admit. With Karupy, debuting at TIFF now feels like the right time. It’s the first film I’m at peace with. Not because it’s my best work, but because I know we gave it everything we had with the time and resources available. If it resonates with people, I’ll be grateful. If it doesn’t, that’s okay too. I’ll be chipping away at the next one. It’s about time I make it up to my younger self for all the years I’ve burned. The feature is next. That’s where all roads have been leading.

How to cite: Nagendrarajah, Nirris and Kalainithan Kalaichelvan. “You Don’t Belong to Anyone: A Conversation on Kalainithan Kalaichelvan’s Karupy.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 7 Oct. 2025, chajournal.blog/2025/10/07/karupy.

Nirris Nagendrarajah (he/him) is a Toronto-based writer whose work has appeared in paloma, Polyester, Fête Chinoise, In the Mood Magazine, Tamil Culture, in addition to Substack. He is currently at work on a novel about waiting. [All contributions by Nirris Nagendrarajah.]

Kalainithan Kalaichelvan is a Tamil-Canadian writer and director whose films have been screened at festivals including the Toronto International Film Festival, the Santa Barbara International Film Festival and the Palm Springs International ShortFest. His recent short films include Junglefowl (2023) and A Feller and the Tree (2021). Also recognised for his work in music videos, he was nominated for a Juno Award for Music Video of the Year. Kalaichelvan has participated in the Netflix-BANFF Diversity of Voices Programme and the Rogers-BSO Script Development Fund Programme, and has received support from the Canada Council for the Arts, the Ontario Arts Council and the Toronto Arts Council. He is an alumnus of the 2024 CFC Norman Jewison Directors’ Lab.