茶 FIRST IMPRESSIONS

茶 REVIEW OF BOOKS & FILMS

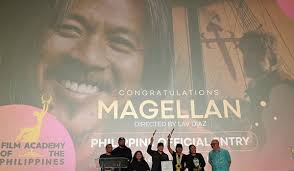

[REVIEW] “Lav Diaz’s Magellan: From Counter-Time to Counter-History” by Ramzzi Fariñas

Click HERE to read all entries in Cha

on Magellan.

Lav Diaz (director), Magellan, 2025. 165 min.

If the art of history is to be excavated, the records to be dug up will definitely show we are all children of the past, no matter how future-oriented one might be. If the history of arts, however, is to be excavated, what will come up is that all artists are children, whatever point in time. That is, anyone in his or her art has always a plaything not to be taken for granted. Take, for example, the English poet and painter William Blake, who, according to Alexander Gilchrist, was “a divine child,” whose playthings were sun, moon, and stars, the heavens and the earth. For the Filipino auteur Lav Diaz, his playthings are no less history and poets, which makes him a human rather than divine child. History has been recurring in Diaz’s works, as seen in his past work, Hele sa Hiwagang Hapis (2016) (2016)—the only work of his I had watched until his recent—which convoluted narrative reimagines the 1896–1898 Philippine revolution and its purpose, flared with fantasy and didactic lyricism. For his future plans, he has talked about adapting into film Noli Me Tangere by José Rizal, the most important novel which had shaped Philippine history. All these have more or less touched history, not forgetting his best-known work, though not history-based, is Norte, Hangganan ng Kasaysayan (2013), rendered in English as Norte, The End of History. What centres this discussion, however, is the present: What to make of Diaz’s Magellan (2025)?

Diaz’s Magellan is a visceral reimagination of the past, by which the titular protagonist goes into the “golden islands” to secure other races for conversion to Christianity. With courage to counter clock time with his signature long shots devoid of cuts, swift action typical of Hollywood films, and even background music as a requisite for any film, Diaz, this time, goes beyond via countering history with a novel narrative. That, though the First Voyage was “glorious” for the Europeans, for Diaz, Magellan’s circumnavigation is rather messy, full of religious irony and unwarranted punishment. By filling colour into that courage, deviating from his standard black-and-white monochrome, Diaz even went to the extent of offering a counterfactual myth-busting: Lapulapu, the one who slew Magellan, did not exist.

As an artist, Diaz never shied away from such bold moves. It is worth recalling some of his playthings are poets, often demystifying them as lost and useless figures for war (such as in Hele), if not being knocked down for being “privileged” (such as in Magellan). While there is much freedom to reckon the poets, history as a playground, however, is no mere concrete jungle where one can rely on Google Maps, that is, one can get away so easily if lost. It is rather a forest of time, by which some who venture into it might not have enough arsenal to get out of it as accurately and as clearly as historians do. Nevertheless, two of the foremost public historians in the country were sympathetic to Diaz’s undertaking. Ambeth Ocampo said no validation was needed when Diaz approached him, for his is a film, not a doctoral dissertation. On the one hand, Xiao Chua, who is also an anthropologist, believes art is not a realm for historians, and as an artist, Diaz has the privilege of interpretation and creativity. In his Manila Times column, however, Chua lucidly compiled first-hand resources and respectable interpretations which affirm Lapulapu was no mere myth, but a real person witnessed not only by the Indios or the ancient Filipinos, but by the colonisers themselves.

At this time of writing, the Filipino Marxist philosopher of history, translator, and digital humanities scholar Ramon Guillermo upped his own research on Lapulapu, headlining it on Facebook as “ON THE EUROPEAN (NOW FILIPINO?) ERASURE OF LAPULAPU,” which, in my understanding, is a subtle hit at Diaz’s historical interpretation. According to Guillermo’s research and analysis, Lapulapu’s “kris” (the traditional Malay blade) left a trace which became the hyphen (“–”) in between the Magellan–Elcano expedition because he was not often mentioned in the universal story of Europe due, perhaps, to reasons of racial supremacy. If not, the voyage itself had a very unacceptable outcome for the Europeans: their first voyager was slain by the one he was colonising, by Lapulapu himself.

The most astute to be recalled is by the Philippine National Artist for Literature, Resil Mojares, who himself was from Cebu, the very land Lapulapu was known to hail from. As he has written in “The Islands According to Pigafetta” from his sublime book Waiting for Makiling: Essays in Philippine Cultural History (2002):

The European “discovery” of the Philippine archipelago is not just an event; it is a text, a construct of words. For “new worlds” to be recognized or apprehended, they had to be produced in words—in the form of narratives of navigation and exploration—and such allied devices as maps, charts, and drawings. Worlds had to be represented, and, inescapably in such representations (literary, visual, popular or “scientific”), much will be discovered as much as will be disguised, distorted, or deleted. Much will be revealed of both seen and seer. (Emphasis mine.)

Magellan is a mesmerising work of counter-history, hence as divisive as it is decisive for Diaz, who has written and directed it. In the eyes of arthouse aficionados and film critics, Diaz is a living god of cinema, a visionary whose works are a sweeping testament against commercial currents and temporal acceleration in art and in life. In the eyes of select historians and other scrutinisers of the past, however, reserved sympathy goes to the filmmaker, because he is only human, all too human, for—in putting emphasis on the fallibility, madness, and ignorance of the coloniser—he unfortunately negated in return the Filipino figure who was as important as him; the one, in fact, who put him down in his conquest. While Diaz succeeded in showing Magellan is no less a mortal than someone divined by the Crowns of Spain and Portugal as the chosen one, as the holy Captain-General, his decision on the existence of Lapulapu as the first leading defender of the archipelago, however, is a reckoning of one of the limits of art—no matter how pivotal the perspective presented, no matter how rigorous the research and the craft rendered—and that is, to successfully merge truth and beauty. More so, to reimagine history in its totality from the other side—the Asian side, the Filipino side.

The Platonist insight of Iris Murdoch underscores this: the excellence of art is not the excellence of life or history in general. What is artful or beautiful can never always be truthful. It can, nevertheless, recall, and in this context it is what makes Diaz and his vision worth the push towards the audience, and perhaps the accolades, especially so as Magellan is the Philippines’ entry to the 98th Academy Awards for Best International Film.

With the maelstrom of history that ever rages in the seas, this is, however, a voyage he will have a hard time countering.

How to cite: Fariñas, Ramzzi. “Lav Diaz’s Magellan: From Counter-Time to Counter-History.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 20 Sept. 2025, chajournal.blog/2025/09/20/magellan-film.

Ramzzi Fariñas grew up in Ilocos Sur and Abra, Philippines. His poems and essays have appeared in Philippines Graphic, Rappler, Ani 41, Write to Power (Cha: An Asian Literary Journal), Voice & Verse Poetry Magazine 聲韻詩刊 , and Digital Hypertext Garden 2020, among others. His short fiction has been included in the zine collections Cheap Lives & Hard Drives: A Cyberpunk Anthology and Open Fire by The Time of Assassins Literary Guild. He is presently pursuing an MA in Philosophy at the University of the Philippines Diliman, while working at night as a Trust & Safety Analyst for a technology and operations company. [All contributions by Ramzzi Fariñas.]