📁 RETURN TO FIRST IMPRESSIONS

📁 RETURN TO CHA REVIEW OF BOOKS AND FILMS

Click HERE to read all entries in Cha on So That You Know.

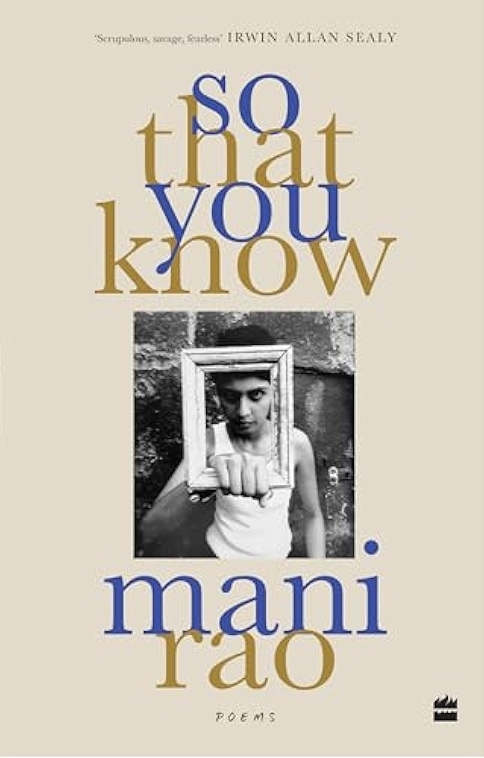

Mani Rao, So That You Know, HarperCollins India, 2025. 312 pgs.

“Isn’t it better to write poems about topics? On the dazzle of rice, for instance. Some reader will still read my life on those rice grains, and make that mistake—were you always like that? But these days I’m craving privacy even from myself. So That You Know.”

From the final lines of the Preface to Mani Rao’s So That You Know, published by HarperCollins India in July 2025, the reader is warned: the ground of this collection should not be ventured upon with the naïveté of a tourist. Here, polite distance does not exist, nor does artful evasion masquerade as detachment. Rao allows us entry, yet holds back at the same time; she tests how much of the self can be borne by the reader, how much can be transcribed before language begins to tremble.

This balance of revelation and restraint makes Rao’s poems powerful. “In any room, there’s only room / for a single poet. Take turns.” The line echoes the Preface’s craving for privacy and points to the necessity of solitude during creation, as well as the impossibility of sharing space in the act of making art.

These poems are intimate. The images are intrinsic to the themes, like skin to bone. “It’s not too cold, I know, / but I had nowhere else / to keep this overcoat / All my suitcases were full / And my closet overcrowded / So I just let it sit / upon my shoulders.” The lines are straightforward, yet carry an intensity—typical of Rao. The unexplained situation, the ambiguity, combined with the simplicity, render the poem both opaque and transparent at once.

Throughout the book, Rao wrestles with language, unable to accept it because of its charms and betrayals. She describes the struggle between language and non-language, a dilemma echoed in modernist and contemporary poetics. In another poem, she writes: “Monkey, we leap from word to word, thick with meaning. / Spider, our words are resilient webs, we make snares / in the colour of air, sweet-smelling and sticky. / Please, do not say a single word. Expressed, dead. You have my word.” Elsewhere, this discontent turns into a plea for freedom from the tyranny of meaning: “Bring me the words without meanings, / words all meanings have abandoned, sentenced to / meaningless.” Once she declares, with her characteristic cold honesty, that even “language can at best mortify thought”, the anxiety becomes naked, even nihilistic.

This concern with language and its failures is evident in style as well. Consider: “Two roots anchored each other / Each both tree and soil / Day and night : lips played at missing / Twilight a lasting a las t.” The syntax fragments. Language itself seems to falter under the weight of longing.

To begin reading Rao is to enter an environment where language is both necessity and deception. Words attempt to capture what language cannot, and T. S. Eliot in Four Quartets reminds us of this creative hysteria: the instruments of articulation cancel each other. In Burnt Norton, he laments: “Words strain, / Crack and sometimes break, under the burden, / Under the tension, slip, slide, perish, / Will not stay still,” exposing the failure of signification when language struggles to convey the unsayable. This battle returns in East Coker, where “the intolerable wrestle / With words and meanings” suggests that poetry is best written in gestures, hints, and guesses, indicating something beyond its own language. Rao’s poetry shares this quality: the ringing music of the interstice between articulation and silence, between the said and the unsayable, a poetics founded on both conscious and unconscious awareness, carrying a hesitancy and yet an essential force.

There are also striking instances of surrealism, where intimacy is haunted: “A haunted house / afraid to die / The echoes fold / Should the poem end there.” The house, like the poem, wavers between annihilation and being, always on the verge of collapse. This oscillation between matter and spirit animates the collection.

Rao’s poetry dwells on materiality and the body. “Your body suits you best / Conducted like a plant / All pores at once / Posture of trunk of leaves the / Petrifaction moment.” Giving and withholding are dovetailed. Even grief assumes corporeal force: “When death fell asleep between my legs / One arm slung over my knee / I pulled her up to my leaking breasts / And heard her grind her teeth.” Death, in Rao’s tempestuous vision, is not abstraction or idea but a restless guest pressing against the world’s skin, intimate and unrelenting. She is merciless even with impermanence: “If everything is impermanent why do you want it / I don’t want anything for ever.”

Several poems draw on Greek myth. Rao’s dramatisation of the story of Ouranos and Gaia is sparse and vivid: “When they sliced his testicles instead / His hands full on her breasts / Jerked a seizure / She ejaculated disbelief / Ouranos drained / Gaia sank.” Elsewhere, she evokes the gesture of Goddess Kali: “Then Tongue stretched / between Earth and Sky / Licked each drop / as it fell.”

Memory, too, takes root quietly but insistently. “Who’s buried under the memory tree / What’s the name of the bird in that nest.” Simple on the surface, the image blooms with unspoken histories and the ache of what is unnamed yet unforgotten.

In these poems, nature is accomplice and mirror. “The gardener of dust is using my frame as a mould for the / shape of future dust”; then: “I crawl into the warm breath of mud, the cooling hands of / satin leaves.” These lines pulse with tactile sensuality, blurring human and elemental, self and world.

Desire speaks in a raw, unmediated voice: “Amorous / but no amour? / Your cock-tip smiles / spurting / moonbeam / There’s a mouth / Doesn’t lie.” The language dances between sacred and profane, cosmic and intimate, never descending into vulgarity.

Elsewhere, Rao questions beauty, and its inevitable twin: “Imperfection haunts beauty / So imagination can rule / Helen haunts imagination.”

The book both mirrors and refracts. It contains humility and defiance, the poet as reflector and witness, acknowledging her limitations and her position: “The poet knows she is mere / reflection / Stays with the metaphor / Some respectful distance from the sun.”

Pauses and turns disrupt expectation, introducing unease. “Again and again in parallel lines my bare feet face the door, welcoming the railroad of time space. But death is not interested when I am.” The poem disintegrates and we are caught in its vacuum. Waiting itself becomes a model of existence.

Rao’s language is marked by syncopated, sharp enjambments and subtle ruptures. Poems beginning with lines such as “By day freckles pop mustard seeds / By night moon glosses grain on lake rims” shimmer with painterly precision. Others sting with aphoristic finality—“Narcissus drowning in onlyness / The rest in duplicity.”

So That You Know is not a heavy book despite its density. Its poems demand attention, but reward it richly, with images that linger long after the pages are turned. Rhythm—the ache of language—is not sound but sensation: “I tore out the wind-chimes / to listen / You were racing through my veins / The curtains did a two-step / and swirled.” Here Rao reinvents intimacy: “For the first time I think to / count your eyelashes / to pluck them / before they’re singed.” Love is shown not as rest but as movement, a Forsterian pursuit.

The poems remain open-ended, perpetual, like echoes impossible to capture. So That You Know: to live multiplied and contradictorily. Rao’s voice becomes a symbol of sacredness rather than eroticism, fragility rather than ferality, ephemerality rather than timelessness. That it sustains such performance is testament to its elasticity.

Ultimately, the book turns back upon itself. It craves privacy, then longs to vanish even as it speaks. “Isn’t it better to write poems about topics? On the dazzle of rice, for instance… But these days I’m craving privacy even from myself.” Yet in writing, Rao gives not only the dazzle of rice, but also the grain of the splintered voice—luminous, unconstrained. So That You Know is not a book to be read at once; it is a book to live with, to return to repeatedly, its lines seeping into the bloodstream. It reminds us that poetry, at its most urgent, is not concerned with answers but with the silence, the exhilaration, and the frightening beauty of the open question.

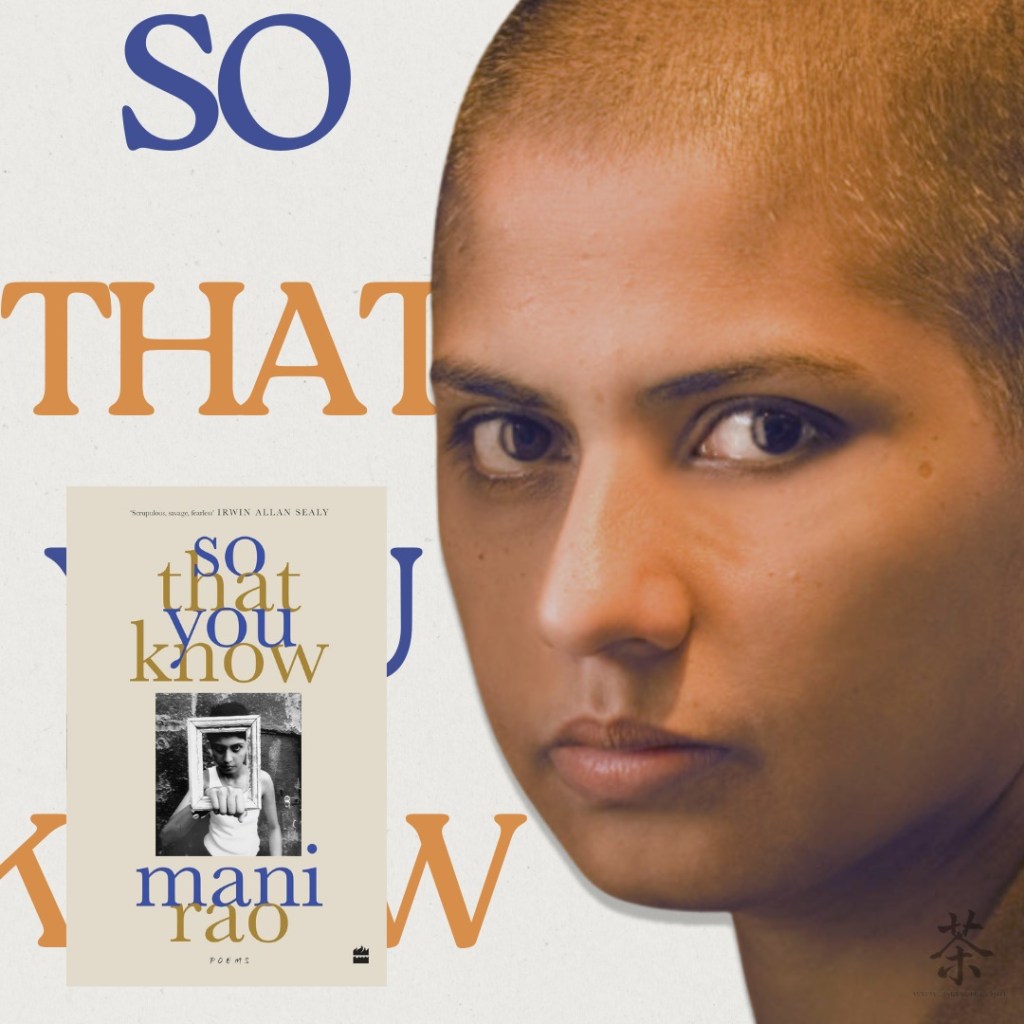

Mani Rao was a contributor to the inaugural issue of Cha, 2007.

How to cite: Nazir, Wani. “Haunted by Words, Hunted by Silence: Mani Rao’s Radical Intimacy in So That You Know.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 11 Sept. 2025, chajournal.blog/2025/09/11/you-know.

A postgraduate Gold Medallist in English Literature from the University of Kashmir, Wani Nazir, hailing from Pulwama, J&K, India, is an alumnus of the University of Kashmir, Srinagar. He is the author of the poetry collections …and the Silence Whispered and The Chill in the Bones. Presently working as a Senior Lecturer in the Department of Education, J&K, he writes both prose and poetry in English, Urdu, and his mother tongue, Kashmiri. A voracious and eclectic reader as well as a reviewer, he contributes his creative works, his “brain-children”, to Kashur Qalam, The Significant League, Muse India, Setu (a bilingual e-journal published from Pittsburgh, USA), Langlit and Literary Herald, Café Dissensus, Learning and Creativity, and The Dialogue Times, a journal published in London. He has received much acclaim for the beauty and depth of his writing. [All contributions by Wani Nazir.]