Editor’s note: This conversation between Shuang Xiao 肖爽 and T. L. Tsim 詹德隆, former director of Chinese University Press, provides a wide-ranging reflection on Hong Kong’s cultural and literary landscape of the 1980s, highlighting Tsim’s collaboration with John Minford on Renditions and the Chinese University Press,, and sharing rich anecdotes about figures such as Stephen Soong and Jin Yong. It documents a pivotal era in publishing and translation, and captures the personal rapport between Tsim and Minford—a bond that has endured for over four decades.

Click HERE to read all entries in Cha on John Minford.

Date: 4 March 2025

Location: Chariot Club, Hong Kong

On a gentle spring afternoon in Hong Kong, I met with Mr T. L. Tsim, former Director of the Chinese University of Hong Kong Press (1984–1994), whose distinguished career encompasses broadcasting, writing, publishing, and political commentary. The interview was conducted as part of my doctoral project on Professor John Minford’s life, work, and intellectual network. Our conversation explored Hong Kong’s vibrant artistic milieu of the 1980s, with particular attention to the landmark translation journal Renditions, the Chinese University Press, the cultural phenomenon of Jin Yong, and the close collaboration between Tsim and Minford.

Shuang Xiao 肖爽 (“Xiao”): Mr Tsim, thank you very much for meeting me. I wonder how you and Professor John Minford (hereafter “JM”) became friends.

T. L. Tsim 詹德隆 (“Tsim”): This dates back to the mid-1980s, when I was the director of the Chinese University of Hong Kong Press (CUP), and JM was the chief editor of Renditions. After a few meetings about the cooperation between Renditions and CUP, we became friends. You could say we “hit it off.” I really like him. One can tell that he is a very cultured person: his language, accent, and the books he has read.

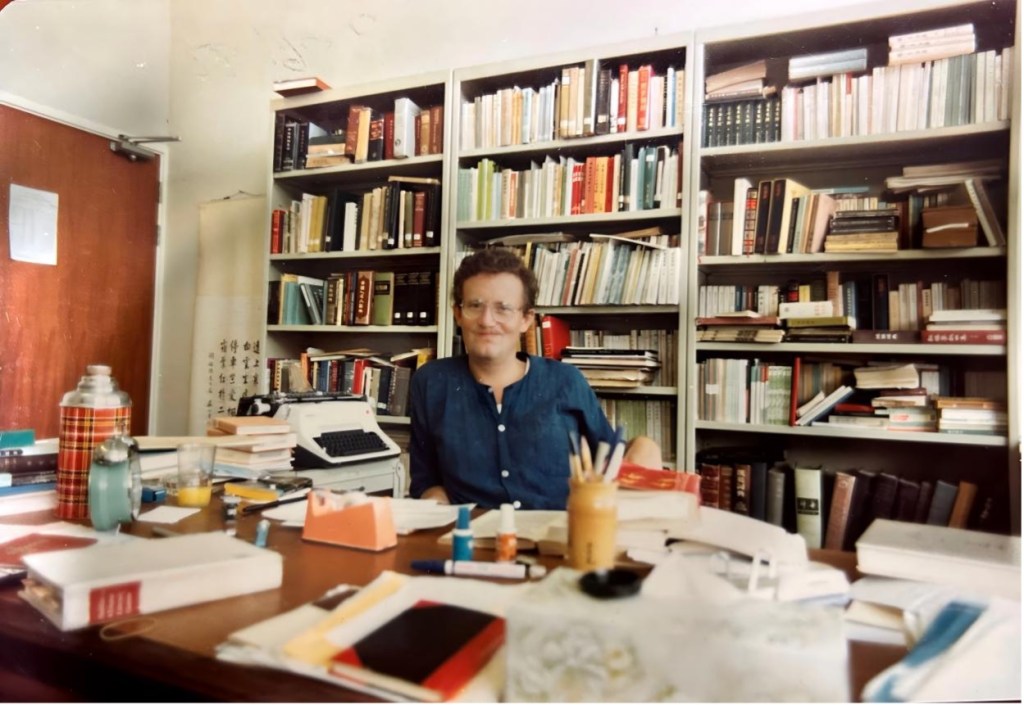

John Minford in the Renditions office, succeeding Stephen Soong as Editor-in-Chief

Xiao: Could you elaborate on how CUP collaborated with Renditions at the time?

Tsim: We would help with marketing and publication, but Renditions was in sole charge of the editing and translation.

Xiao: Renditions launched its Paperbacks series in 1986, with you listed as one of the series editors. The first four titles were Yu Luojin’s A Chinese Winter’s Tale; Xi Xi’s A Girl Like Me and Other Stories; Chen Jo-hsi’s The Old Man and Other Stories; and Tao Yang’s Borrowed Tongue. Were you involved in the selection process?

Tsim: No, the whole business of the Paperbacks was John’s idea. The original Renditions Books were hardbacks, which made them expensive. John really wanted to make Renditions more accessible and affordable for general readers, so he planned and launched the Paperbacks. The choice of what to publish was up to the editors of Renditions. Our Press mainly coordinated the publishing and distribution activities.

Xiao: JM mentioned that the launch party was held at Hanart gallery—an iconic space for contemporary Chinese art since the 1980s, owned by the eminent curator Johnson Chang Tsong-zung 張頌仁. I came across the guest sign-in book from the event in JM’s archive, which recorded a distinguished gathering that included Hsiung Shih-I 熊式一 (1902–1991), Stephen C. Soong 宋淇 (1919–1996), and Leung Ping-kwan 梁秉鈞 (1949–2013), among others. Could you tell me more about that evening?

Tsim: It was an impressive launch celebration. The owner of Hanart was JM’s friend. I think JM makes friends very easily. The series launch there also highlighted Hong Kong’s creative boom in the 1980s.

Xiao: During JM’s years at Renditions, Stephen C. Soong—the founding figure of the journal—was his great patron, almost a father figure. Would you share more about Soong?

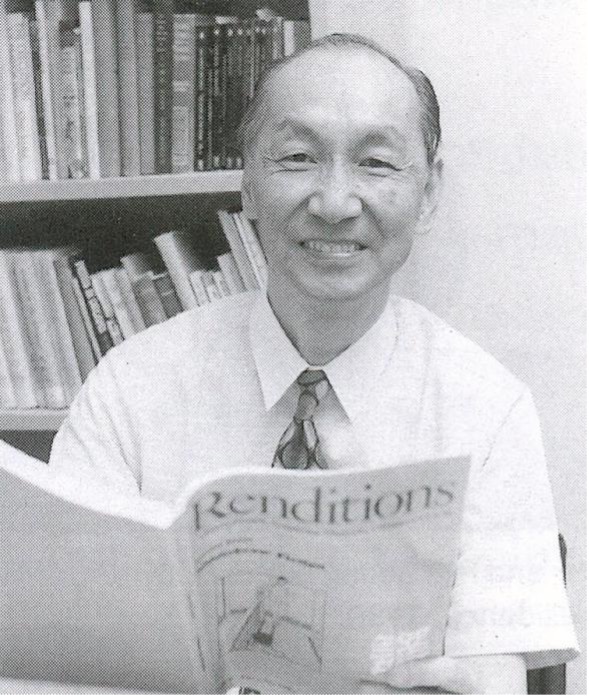

Stephen Soong and Renditions, via

Tsim: Stephen Soong was a figure that I liked, admired and respected. He was from one of the most distinguished, sophisticated, and cultured Shanghai families. His father, Soong Tzun Fong 宋春舫 (1892-1938), reportedly possessed the largest collection of French literature in China. I first knew of Stephen from his work in the Hong Kong film industry in the 1950s. It was with Stephen’s encouragement that Eileen Chang 張愛玲 (1920-1995) started to write film scripts. When the Chinese University of Hong Kong was founded in 1963, its first Vice-Chancellor Dr Li Choh-ming 李卓敏 (1912-1991) invited Stephen to be his special advisor. I think one of the reasons for that was that Stephen really had a lovely hand. He wrote very elegant and excellent prose. So, when JM joined CUHK in 1983, Stephen became an early admirer of JM and his work. Together with his father-in-law, the eminent David Hawkes (1923-2009), JM translated Hongloumeng 紅樓夢 (The Story of the Stone, hereafter Stone). I think Stephen probably believed that Hongloumeng was untranslatable, but Hawkes and JM did it, and did it superbly, so much so that decades, perhaps two generations after their Penguin version (1973-1986), there still has been no need for a second translation. This is their definitive work.

Xiao: What brought JM and Soong closer was their shared obsession with Hongloumeng. JM was translating the final volume of The Story of the Stone during his time at CUHK, while Soong, a renowned Redologist 紅學家, had published the influential Hongloumeng’s Journey to the West 紅樓夢西遊記: 細評紅樓夢新英譯 in 1976, a commentary on Hawkes’s first volume of Stone.

Tsim: Yes, they became “real buddies.” When JM encountered any expressions that were difficult to translate, he would go to Stephen. A famous example of this was described in JM’s eulogy of Stephen Soong after his death in 1996. One day, JM asked Stephen for help with a tricky passage in Stone. Then the following morning, Stephen acted out the entire scene for him. You need to quote that, because, for me, that was a magic moment in translation. It illustrated how difficult translation is as an art, and how involved Stephen and JM were in trying to come to grips with a particularly difficult passage in Stone.

Xiao: Yes, I came across that well-known story in JM’s obituary for Stephen in Translation Quarterly (1997). It was the scene in which Jia Baoyu 賈寶玉 and Lin Daiyu 林黛玉 converse in Zen riddles. Turning now to Renditions—unfortunately, it folded in 2024. How did it fare in the 1980s? Was it considered popular?

Tsim: The word “Popular” has to be defined, because in Hong Kong, if you write a book in English and you manage to sell 1,000 copies, that is regarded as “popular”, whereas in Mainland China, that would be regarded as “unpopular”. I would call Renditions, or its Paperbacks series and so on, “highly regarded”. You could never sell a lot of copies. Most of them would be taken up by universities offering Chinese Studies, by libraries, or by students of translation like yourself, but whether there was ever a bigger, wider audience out there, I doubt very much. Still, they did well, given the circumstances for such kind of books.

Xiao: Theodore Huters, the final editor-in-chief of Renditions, explained the closure in a recent interview: “With libraries being under financial constraints for the last 10 to 20 years, a lot of them had to cut their budget. As a result, we unfortunately lost a lot of circulation in that sector.”1

Tsim: I think this is probably true. Universities the world over depend very much on government funding. If government funding is stretched, then someone who wields the axe cuts the budget. Unfortunately, that happened to Renditions.

Xiao: On another matter, I would like to ask about a letter JM wrote to you in 1989. At that time, he had just received a generous grant from the Taiwan Council for Cultural Construction and Development 臺灣行政院文化建設委員會 to translate the complete Liaozhai zhiyi 聊齋志異. He approached you to ask whether CUP might be interested in publishing it, and you agreed. Yet the publication never materialised. Could you explain why?

Tsim: Because he never finished it on time, and I left the CUHK Press in 1994. All I can say is this: John, because of who he is and how good he is, gets lots of invitations to translate this and translate that. You remember the famous invitation from Jin Yong 金庸 (1924-2018)? John is such a nice person that he often finds it difficult to say no, so he will take offers. It does not surprise me that from time to time he has difficulties in meeting deadlines.

Xiao: Since you have mentioned him, perhaps we can now turn to Jin Yong. CUP published The Fox Volant of the Snowy Mountain 雪山飛狐 in 1993, translated by Olivia Mok. This was the first appearance of a Jin Yong novel in English book form. You wrote the foreword to that volume. Could you tell me more about it?

Tsim: I know that Olivia Mok started the translation with JM as her supervisor. She was showing drafts and translations to John. I think John probably made suggestions: some corrections here or changes there. Then there was a falling out, but I don’t know the full story. They started working together on this project, but later Olivia Mok decided to publish the work alone. Have you read it?

Xiao: Not really—I read your “Foreword” and a small portion of the translation. I did, however, find manuscripts in JM’s archive which show his guidance for Mok during the early stages of her work. JM once mentioned that you may also have helped her refine the translation.

Tsim: No, I do not recall helping her with the translation. I barely know her, we perhaps only ever had one meeting. When you’re a publisher, you send the manuscript out for review. If the response is positive and suggests there’s a market for the translation, you go ahead and publish it.

Here is my theory of translation. First, you need to know what kind of writing it is. If it is a piece of legislation, you want a lawyer to translate it, because the translation of law has to be very exact. You should not deviate from the words in the original text. But if it is literature or fiction, you want someone who is a literary writer. The translation of literature gives you some licence. Some people would call it “poetic licence”, or “translator’s licence”. You can vary things slightly, so as to convey the mood, emotions, feelings, and so on. There is some leeway. Then I come to my second part. When you are translating from Chinese to English, a smart way to do it is to have the first draft translated by a Chinese scholar, and the second draft translated by a native writer who is a literary man. The first draft needs to be close to the original, but if it is too close, it does not read well, not like an English novel. The second draft, with the help of a native writer of English, will become much more readable in English. Now, JM, being the native writer and a literary man, is best suited to do the job.

Xiao: From 1997 to 2002, the three-volume The Deer and the Cauldron 鹿鼎記, translated by JM and David Hawkes, was published by Oxford University Press. This translation played a significant role in canonising Jin Yong’s wuxia fiction in the West. For instance, it helped pave the way for Jin Yong’s nomination for an honorary doctorate from the University of Cambridge in 2005, and he was considered for the inaugural Newman Prize for Chinese Literature in 2009, with Deer as his representative work. What do you think of Jin Yong and his oeuvre?

The Deer and the Cauldron

Tsim: I have met Jin Yong/ many times. He is an extraordinary man who has a hand in a lot of things. He first worked at the Ta Kung Pao 大公報, then started writing movie scripts, then founded his own newspaper the Ming Pao 明報, and he wrote all these, what I would call swashbuckling novels, wuxia xiaoshuo 武俠小說. He is a man of many talents. I do not wish to diminish his achievements. When talking about his novels, I think he matches Walter Scott (1771-1832) and Alexandre Dumas (1802-1870). JM might disagree with this. But Jin Yong is basically writing to that kind of audience, that kind of genre, stories about heroes and villains, love and revenge, adventures and swordplay. His works are best judged on this basis. Jin Yong would never have won the Nobel Prize, in my opinion, although he wanted it. To win the Nobel Prize, you have to deal with what is commonly known as the human condition, you have to plumb the depths of human emotions, and you have to be completely, brutally honest with yourself. You don’t get that in Jin Yong’s novels—they may be superficial, but they make terrific movies. For that reason, he would never have won the Nobel Prize, even if he had the best translator in the world.

Xiao: Actually, I think JM would agree with you on the Alexandre Dumas comparison—he confirms as much in his forthcoming memoir. I would like to return to the 1980s. Was that, in your view, a golden era for artistic creation and publishing?

Tsim: It was a really good time, with new writings by PRC writers coming out: Bei Dao 北島, Gu Cheng 顧城 (1956-1993), among others. I think each CUP director seeks to do more than was done before, wants to branch out in new directions, and tries to do a bit more within the constraints of resources. So we collaborated with JM to launch the Renditions Paperbacks, and I started to publish novels, for example, Bei Dao’s Waves 波動. That was our first novel, CUP’s first novel. In 1986, we not only published the translation Waves by Bonnie S. McDougall and Susette Cooke, but also the original Bodong 波動 in Chinese. Furthermore, we started to publish what is called “general books”, meaning non-academic books.

English and Chinese Versions of Waves

Xiao: In that sense, rather like the Renditions Paperbacks—more oriented towards the general reader?

Tsim: Yes, exactly. Academic books are full of footnotes and glossaries. With general books, you don’t expect people to trace every quotation. Therefore, it is easier to do, and it sells more. My successor, the current director of CUP, Ms Gan Qi 甘琦, has done very well. She published the Chinese translation of Ezra F. Vogel’s (1930-2020) work on Deng Xiaoping, which was a major undertaking. I really salute her, take my hat off to her.

Xiao: What do you think of JM as a translator?

Tsim: He is definitely first-rate. I’ll give you one example. He worked with Joseph S. M. Lau 劉紹銘 (1934-2023), who was an early admirer of JM’s work. Joseph once told me a story, which I remember till today. There’s a famous Beijing rock star, Cui Jian 崔健, who in 1986 wrote a wonderful song called “Yiwu Suoyou” 一無所有. Most translators would have translated it as “I Have Nothing”, but Joseph said he thought John’s translation was much better. He translated it as “Nothing to My Name”.2

Xiao: Oh, that is now the official English title of the song. I found it on Wikipedia as “Nothing to My Name”. I had no idea it originated with JM.

Tsim: That was JM’s work. His translation is much more cultured. It is accurate but also, I have to use this word, not “pedestrian”, or common.

Xiao: It even sounds like a song title from the hippie years. As you know, JM himself was a hippie during the 1960s and 70s. Since you have mentioned his collaboration with Lau, it is worth noting that they went on to produce an important textbook, Classical Chinese Literature: An Anthology of Translations (2000). In a letter to David Hawkes dated September 1985, JM wrote: “The main project I am embarking upon this year (over and above teaching and producing Renditions) is the compilation of a two-volume anthology of Traditional Chinese Literature in Translation (from the beginning to the end of the Qing). The Chinese University Press has commissioned it from me and from Joseph Lau of Wisconsin University. They are very serious about the whole thing and want to provide a standard textbook for undergraduate students.”3 This project, begun in 1985, culminated in the first volume published in 2000, followed the next year by A Chinese Companion to Classical Chinese Literature 含英咀華(上卷), issued by CUP. This leads to my next question: what is your assessment of JM as a scholar?

Bilingual Versions of Classical Chinese Literature: An Anthology of Translations

Tsim: I think he’s got a fantastic mind. He has this very rare gift which is sensibility and sensitivity. He understands nuances. He reads a text meticulously to get the true sense of the words the writer used. I think it was for this reason that the eminent scholar–writer–translator Joseph Lau chose to collaborate with him on that monumental work the two of them did for The Chinese University Press and Columbia University Press. I am referring, of course, to Classical Chinese Literature: An Anthology of Translations. It was Joseph’s idea to do the anthology, a most difficult opus. It was also Joseph’s idea to work on this with JM and no other. This shows you how much he respected JM as a scholar. I can only agree.

Xiao: The anthology has become widely recognised as a standard textbook in courses on Chinese literature for English-speaking students. Alongside the contributions of JM and Lau, you also played a vital role in shepherding the project from its early stages to publication. JM recently said you were the “midwife” who “warmly welcomed and steered through its infancy”, adding that “without the wholehearted support of TL and the CU Press it would have been yet another of those notorious unfinished JM projects!”4

In a recent email to JM (17 February 2025), you wrote: “I would be happy to talk with Jessica about the prankster John Minford in the 1980s!” Why did you describe him as a “prankster”?

Tsim: A prankster is somebody who loves pranks 惡作劇, stirs up a bit of trouble, but with good humour, not with any evil intention. He is just fun-loving, not too serious.

Xiao: Yes, JM’s personal motto is “Seria Ludens”—playing with serious things. His forthcoming memoir, to be published by Hong Kong University Press, actually bears the same title: Seria Ludens. It captures perfectly a mind that is curious, playful, and anything but pedantic. Thank you so much for sharing your thoughts with me today. It has been a great pleasure to talk with you.

Tsim: It is also a delight to talk about things that are so close to my heart.

Final Thoughts: In the flourishing cultural and artistic climate of 1980s Hong Kong, Tsim became Director of CUP in 1984, while JM assumed the role of Editor-in-Chief of Renditions in 1985. Both were newly appointed, eager to innovate and expand their respective institutions, and they quickly “hit it off”, beginning a close collaboration. Against this backdrop, Renditions published post-Mao writings for the first time and launched its Paperbacks series, while CUP released its first novel, Waves, and began publishing general books. These initiatives not only mirrored the spirit of the times but also reflected their own drive for innovation. The rapport they formed then has grown into a deep friendship lasting more than four decades. Perhaps it is fair to say that these two “pranksters”—curious, playful companions—are still at work, sending words from page to print.

Acknowledgments: I am profoundly grateful to Mr. Tsim and Professor Minford for their generous support during this interview. I also wish to express my sincere thanks to the Chinese University Library and the Chinese University Press for their kind assistance.

- “Bringing the beauty of Chinese literature to the English-speaking world,” CUHK in Focus, accessed Sept. 10, 2025, https://www.focus.cuhk.edu.hk/en/20250226/bringing-the-beauty-of-chinese-literature-to-the-english-speaking-world/059arts/. ↩︎

- This translation first appeared in Seeds of Fire, edited by Geremie Barmé and John Minford, published in 1988 by Hill and Wang New York. The book was an expanded version of the 1986 Seeds of Fire published by Far East Economic Review Ltd. ↩︎

- The original correspondence is in the possession of the Taiwan collector, Soong Shu-kong 宋緒康. Mr Soong and Prof. Minford kindly make these files available for my research. ↩︎

- John Minford’s email to Shuang Xiao, 2025. ↩︎

How to cite: Xiao, Shuang and T. L. Tsim. “From Page to Print: In Conversation with T. L. Tsim about Renditions, CUHK Press, and his Fellowship with John Minford.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 11 Sept. 2025, chajournal.blog/2025/09/11/T-L-Tsim.

Shuang Xiao 肖爽 is currently pursuing a PhD in Chinese Studies at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. Her research interests encompass Translation Studies, Chinese Studies, Comparative Literature, and Cultural Studies. She has published both scholarly and translation work in Comparative Literature: East & West, Ming Pao, The World of English, among other venues.

T. L. Tsim 詹德隆, who writes under the pen name T. L. Tsim, is a writer, broadcaster, and political commentator. He was educated at St Paul’s College, the University of Hong Kong, and the University of Manchester. From 1984 to 1994, he served as Director of the Chinese University Press. He began his writing career at The South China Morning Post in Hong Kong with a column entitled “One Man’s View.” He also writes in Chinese and, for many years, contributed a weekly column to the Hong Kong Economic Journal. His Chinese essays on politics and culture were later collected in a six-volume series, From Culture to Civilization (Oxford University Press, Hong Kong). His first English novel, Between Two Shores, was published by the Chinese University of Hong Kong Press in 2020.