TIFF 2025

▞ 10. The Archivist’s Film: A Conversation on Kunsang Kyirong’s 100 Sunset

▞ 9. She Was Screaming into Silence: A Conversation on Cai Shangjun’s The Sun Rises On Us All

▞ 8. You Don’t Belong to Anyone: A Conversation on Kalainithan Kalaichelvan’s Karupy

▞ 7. The Paper Boy: On Park Chan-wook’s No Other Choice

▞ 6. Saigon Does Not Believe In Tears: On Leon Le’s Ky Nam Inn

▞ 5. The Need for Change: On Kei Ishikawa’s A Pale View of Hills

▞ 4. The Angel of Death: On Jafar Panahi’s It Was Just An Accident

▞ 3. Of Eros & Of Dust: On Ratchapoom Boonbunchachoke’s A Useful Ghost

▞ 2. Light At The End of the Labyrinth: On Genki Kawamura’s Exit 8

▞ 1. Affairs of the Heart: On Cai Shangjun’s The Sun Rises On Us All

Genki Kawamura (director), The Exit 8, 2025. 95 min.

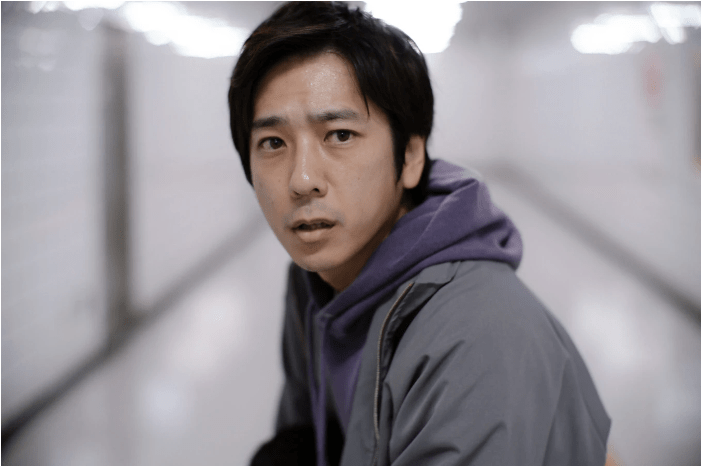

Genki Kawamura

The bolero—the genre and the dance—is defined by its sharp turns, sudden pauses, and its distinctive triple time. That the bolero, in particular Ravel’s majestically divine Boléro of 1928, should bookend Exit 8, a new film from the acclaimed producer, novelist, and filmmaker Genki Kawamura, feels entirely apt. Premiering in the Midnight Screening sidebar at the Cannes Film Festival and now making its North American debut at the Toronto International Film Festival, the film follows three men caught in an endless loop where progress is at once spasmodic and regressive. Kawamura has also revealed that his storytelling is guided by the traditional Japanese form of Rakugo, “which often weaves three seemingly unrelated elements to compel the plot,” as he explained in an interview with The Japan Society Review.

The film begins, as if inside a virtual reality simulation, within the head of The Lost Man (Kazunari Ninomiya), an asthmatic temp worker on his morning commute, scrolling through Twitter as images of water and deformed rats flicker across his feed. Ravel plays in his AirPods until his attention is drawn to the shrill cry of a newborn. He witnesses a confrontation between a man and the baby’s mother; yet, like the other passengers, he does not intervene. Instead, he returns to Boléro and contemplates his reflection in the glass, before his reverie is broken by a call from an ex-lover informing him that she is pregnant.

On the platform, struggling for breath in the throes of a panic attack, he finds the hallway repeating itself. A new reality emerges: he is trapped in a game whose rules, posted on the wall, are brutally simple—spot the anomalies in the corridor, turn back as soon as you see one, and repeat the process seven times in order to escape. At first, it appears straightforward. Yet as he scrutinises the environment—the posters, the vents, the lockers, the overhead signs—he finds that human frailties such as impatience, pride, and excitement impede his progress. The smallest of deviations—a pair of animated eyes on a poster, a misplaced knob, an inverted arrow—thwart his attempts. Again and again, like Sisyphus, The Lost Man begins the hallway anew. Kawamura has explained that the set itself is divided into three distinct sections—the Kubrick set, the Hitchcock set, and the Mizoguchi set—underscoring the film’s formal precision.

When the film shifts perspective, we encounter The Walking Man (Yamato Kôchi), en route to visit his son, who finds himself accompanied by The Boy (Naru Asanuma), a runaway fleeing an unkind mother. Their partnership grants them double the vigilance, yet their scenes reveal something larger: Kawamura and co-screenwriter Hirase Kentarō are less interested in escape than in staging pressure tests of human weakness and temptation. The Boy, slow to speak but unclouded by ego, emerges as the key to endurance and, perhaps, deliverance.

Through Keisuke Imamura’s fluid long takes, Sakura Seya’s incisive editing, and a droning score by Shōhei Amimori and Yasutaka Nakata, Kawamura succeeds not merely in adapting the mechanics of the game but in replicating the sensation of playing it. Soon, we, too, are scouring the corridors for anomalies, only to feel the sting of futility when the cycle resets. Fans of the original game may be startled by the wealth of anomalies brought to the screen—the wallflower, the double trouble, the false tiles—while the narrative deepens through The Lost Man’s private struggle with impending fatherhood, complicated further by the bond he forms with The Boy. “No one really knows what’s right,” his girlfriend (Nana Komatsu) reminds him.

Like Ravel’s Boléro, which culminates in a thunderous crescendo, Exit 8 strives towards a climax of both sound and emotion. Yet what lingers most is the return to the subway carriage in the final scene, now from the reverse perspective. Once again, The Lost Man witnesses the man berating the mother of the crying child. Once again, no one intervenes. Kawamura lingers on Ninomiya’s face—eyes reddened and wet with tears—as the entirety of his tribulations seems to course through him. The image recalls Maurits Escher’s Möbius Strip, glimpsed earlier on a poster, with its nine ants locked in an endless loop. “I keep going around in circles,” The Lost Man remarks early on. But after witnessing change, does the ant itself become changed?

The answer depends on whether you can spot the anomalies.

How to cite: Nagendrarajah, Nirris. “Light At The End of the Labyrinth: On Genki Kawamura’s The Exit 8.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 5 Sept. 2025, chajournal.blog/2025/09/05/exit.

Nirris Nagendrarajah (he/him) is a Toronto-based writer whose work has appeared in paloma, Polyester, Fête Chinoise, In the Mood Magazine, Tamil Culture, in addition to Substack. He is currently at work on a novel about waiting. [All contributions by Nirris Nagendrarajah.]