📁 RETURN TO FIRST IMPRESSIONS

📁RETURN TO CHA REVIEW OF BOOKS AND FILMS

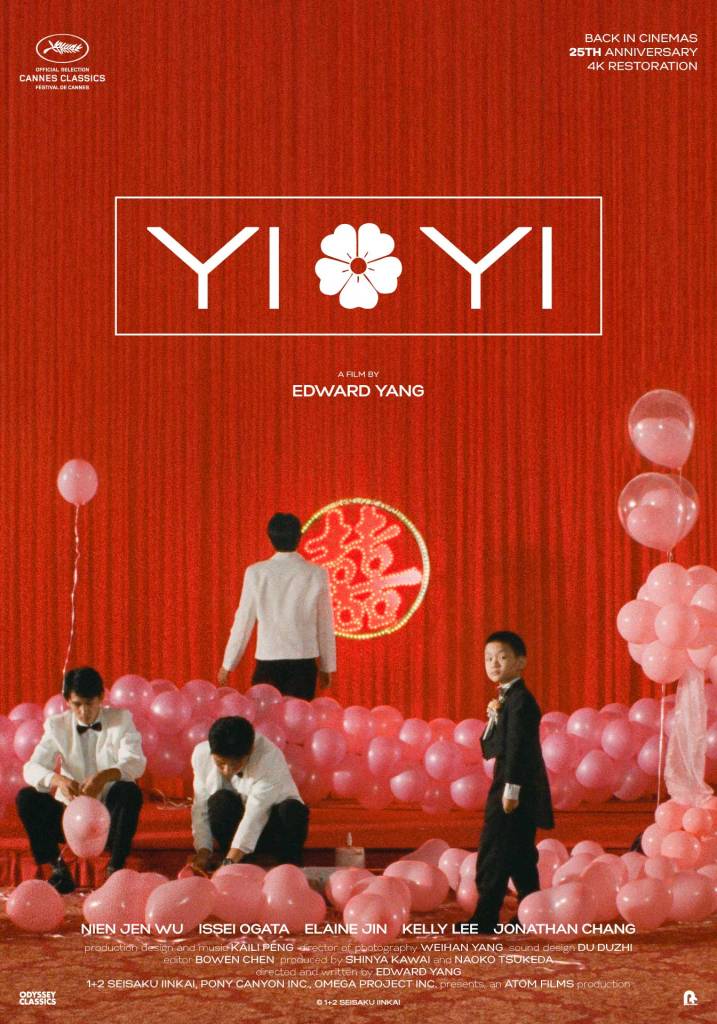

Edward Yang (director), Yi Yi, 2000. 173 min.

Edward Yang’s Yi Yi opens in a register of melodrama. A frantic woman bursts into her ex-boyfriend’s wedding venue, collapses before his mother, and wails her apologies. As flustered relatives attempt to prise them apart, she releases a piercing howl towards the unseen, heavily pregnant bride: “Come out here and show your face!”

And then the storm subsides. The ceremony proceeds more or less as expected, the guests trading benign remarks about the prevalence of shotgun weddings; the newlyweds, A-Di and Xiao Yan, look faintly embarrassed yet broadly content. Something altogether different begins, almost imperceptibly, to take shape: this is anti-melodrama. A film in which both nothing and everything occurs, Yi Yi endures as a moving meditation on human connection and the art of storytelling—so much so that it has returned to cinemas this summer in celebration of its silver anniversary.

Rather than adhering to a single linear narrative, the film is composed of intersecting strands that converge and drift apart across time. When A-Di’s elderly mother suffers a stroke that leaves her comatose, the family are compelled to confront the meaning of their own lives as they anticipate her passing. This incident provides the film with its central axis, yet life continues in spite of her silence. Unable to bear her mother’s condition, A-Di’s sister Min-Min absents herself at a Buddhist retreat; in her absence, her husband NJ struggles to salvage his faltering business and, in the process, rekindles contact with his first love, Sherry. Meanwhile, NJ’s children wrestle with their own growing pains: his teenage daughter Ting-Ting finds herself entangled in a love triangle, while his young son Yang-Yang is subjected to the cruelties of classmates and the tyranny of a schoolteacher.

There is no denying the film’s languid tempo. As quarrels dissolve into gradual reconciliations and weighty business ventures are floated, abandoned, or betrayed, viewers may well question the direction of this meandering narrative. Each time the characters appear poised upon the brink of revelation or catastrophe, these sharp instants of joy or anguish are quietly folded back into the fabric of ordinary life. A-Di, transformed from parasite to prosperous businessman, is ruined by a treacherous partner—only to recover his fortune when the culprit is exposed and arrested. NJ spends a weekend in Tokyo with Sherry, reliving their adolescent romance, but resists consummation, and they part once more. Soon a more troubling question arises: not where the story is going, but where we ourselves are heading.

It is, after all, a question that cinema has always asked. Where are we going, and what is the purpose of it all? Consider Celine Song’s Past Lives (2023), in which two Korean childhood friends reunite after decades, only to realise that time has irrevocably separated them—much like NJ and Sherry. Both films dwell upon an abiding loneliness and the anxiety that human ties, however deeply felt, may never reach fulfilment. Or consider the Daniels’ Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022), with its plaintive yet strangely galvanising refrain: “nothing matters”. The search for meaning in the patterns of daily existence remains, now as ever, inescapably our own.

I suspect Yang would have got on rather well with the Daniels, had he still been alive. He, too, offers a worldview at once plaintive and strangely motivating: there is no final tragedy, nor any consoling happy ending towards which events inexorably build. The essence of the film, he suggests, lies instead in the quiet, quotidian images that connect its moments of intensity: the girl next door practising the cello, NJ blissfully absorbed in music at his office desk, Ting-Ting’s potted plant blooming slowly upon the windowsill. In weaving together such highs, lows, and all that lies between, Yang intimates that anticlimax is not a flaw but the point itself—within the film, as in life. The only certainty that endures is the passage of time.

How, then, are storytellers to represent a world that stumbles forward haphazardly, resisting every attempt at coherence? Here the film becomes self-reflexive. NJ’s inquisitive young son Yang-Yang—his name, perhaps, derived from Edward Yang’s own—possesses all the instincts of a nascent artist. Perceptive and restless, he is drawn to the camera, seizing every opportunity to record his surroundings. When, at his grandmother’s funeral, he declares his wish to “help other people see what they can’t see” through his photographs, the words resonate unmistakably as Yang’s own credo. In this sense, Yi Yi becomes an affirmation of the power of representation: when the filmmaker resists the impulse to impose narrative order upon a tangled world, and instead commits to the act of attentive observation, art emerges. Yet even this affirmation is shadowed by unease. Yang acknowledges, too, that cinema can never fully encompass the intricacies of lived experience. Often the camera withdraws from the characters at decisive moments, lingering instead upon reflective surfaces. After NJ confesses to Sherry that she is the only woman he has ever loved, the camera drifts towards the window of her hotel room, where we perceive her only as a reflection as she sits alone, weeping. Representation, the film admits, is always refracted—several degrees removed from life itself.

That Yi Yi refuses to present artistic creation as a panacea for human turmoil is entirely apt. A film so deeply invested in resisting melodrama could not, without hypocrisy, exalt art as more potent than it truly is. If anything, Yang’s candour is what renders the work so compelling. He knew himself to be little more than a child peering through a lens, striving to compose a moving image of the world for the rest of us to witness. A quarter of a century later, it is still unfolding before our eyes.

How to cite: Cho, Keziah. “Everything, Nothing, All at Once: Edward Yang’s Yi Yi.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 2 Sept. 2025, chajournal.blog/2025/09/02/yi-yi.

Keziah Cho is an English Literature graduate from University College London and will begin a Master’s degree in English at Cambridge University this October. Her poems have appeared in Voice and Verse, The Foundationalist, Crank Literary Magazine, Emerge Literary Journal, and Pi Magazine. As a student journalist, she has also published articles in Cha, Pi Media, The Cheese Grater, emagazine, and Empoword. When she is not writing, she is likely baking up a storm in her kitchen. [All contributions by Keziah Cho.]